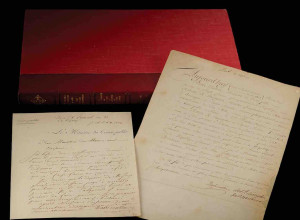

Berenice Alcántara Rojas, professor of History at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Mexico (UNAM), translated this portion of the text appearing in Book 12 from Nahuatl to Spanish together with her colleague Professor Federico Navarrete Linares. In 2015, the codex was added to UNESCO's Memory of the World Register.

“The Florentine Codex’s version of the history of the conquest highlights how this war was essentially an internal conflict between different Indigenous groups who saw the arrival of strangers as an opportunity to resist having to pay tribute to the Aztec Empire,” said Rojas. “When the Spaniards initially attacked the Mexica capital, they were swiftly driven out. Only when aided by various groups of Indigenous allies, as well as by the spread of a terrible smallpox epidemic, did they manage to force the ruler Cuauhtemoc and other Mexica leaders to capitulate. The codex is a critical document to understanding the colonial past of Mexico and how this past still shapes the country today."

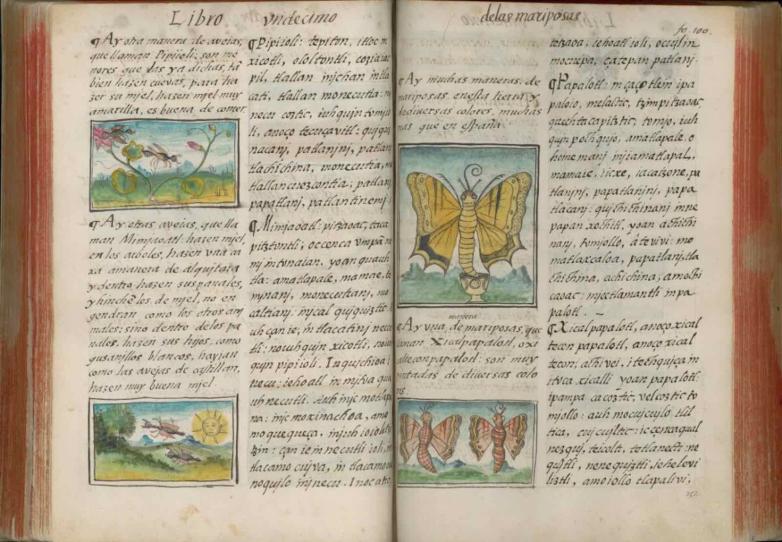

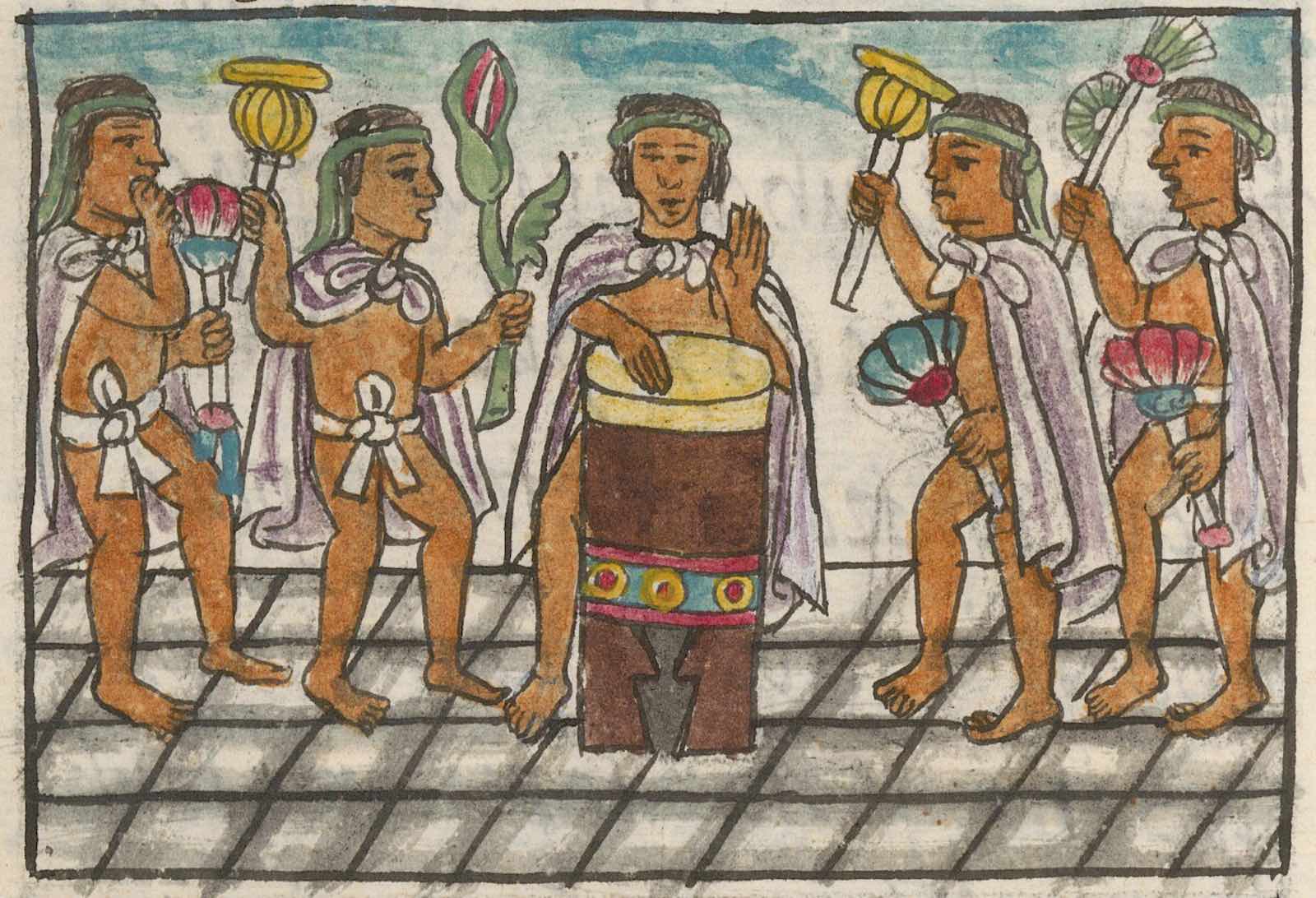

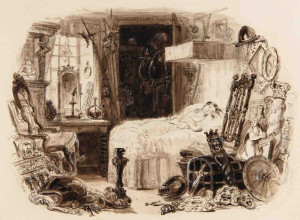

Although the Florentine Codex has been digitally available via the World Digital Library since 2012, for most users it remained impenetrable because reading it requires knowledge of 16th-century Nahuatl and Spanish and of pre-Hispanic and early modern European art traditions. The codex’s images have, moreover, received far less scholarly attention compared to the texts because they were relatively inaccessible until 2012. These images are critical because they provide vivid depictions of Mexica life, objects, rituals, and historic moments, as well as the acts of everyday people.

In 2016, Getty partnered with institutions and scholars in Italy, Mexico, and the U.S. to create a comprehensive and enhanced digital edition of the codex that could be explored by anyone who was interested in learning more about it. This has meant engaging with experts in the Nahuatl language, scholars of Mexican and Spanish colonial history, and software engineers to analyze the codex and assemble its elements online.

“The goal of the Digital Florentine Codex is to bring the three narratives—the two alphabetic texts and the nearly 2,500 hand-painted images—together in a format that makes them easily accessible to the public,” said Kim Richter, the initiative’s principal lead at the GRI. “Our scholarly team conducted extensive research on the images and meticulously tagged each of them with multilingual keywords to make them searchable."

“The website makes it easy to search for any topic about Mexica culture and language,” says Alicia Maria Houtrouw, Digital Florentine Codex project manager at the GRI. “From the homepage, you can browse curated subjects or search the texts and images via keywords. For instance, searching for “woman” (or ‘mujer’ in Spanish or ‘cihuatl’ in Nahuatl) will display the relevant images tagged with these keywords. This ability to search the codex’s texts and images in various languages makes the content of the codex readily discoverable.”

The project also spotlights the once widely used Nahuatl language as both ancient and enduring, appearing in commonly used words in English and Spanish like tomato, chili, chocolate, coyote, and elote. By integrating content in a modern variant of Nahuatl, the website connects Nahuatl’s 1.5 million modern speakers to a critical historical resource and supports contemporary revitalization efforts of this endangered language.

The Getty team collaborated with native Nahuatl speakers based at the Instituto de Docencia e Investigación Etnológica de Zacatecas (IDIEZ), an institution dedicated to teaching and revitalizing Nahuatl. Working with his colleague Sabina Cruz de la Cruz, Eduardo de la Cruz Cruz, director of IDIEZ, translated thousands of tags to Eastern Huasteca Nahuatl, wrote a summary of the historical narrative of the conquest of Mexico, and recorded his reading of that historical narrative as audio.

“I kept thinking about how today in certain places in Mexico there is violence against Indigenous peoples,” said Cruz Cruz. “Working on projects like this gives me hope that they can foster greater knowledge, awareness, and appreciation of Nahua culture, which is so integral to the Mexican national identity."

Members of the project had the many Indigenous and Mexican people living in Los Angeles (where Getty is based) in mind when they organized a workshop for teachers to share knowledge about the Florentine Codex with local schools. Kevin Terraciano, professor of History at UCLA and co-director of the project, led this collaborative outreach to K-12 educators.

"There are more people of Mexican descent living in Los Angeles than any other city outside of Mexico,” said Terraciano. “Working with local teachers to develop curricula around original Indigenous sources like the Florentine Codex gives them more tools to highlight the diversity of perspectives and voices about Mexican history. The Florentine Codex is the most remarkable cultural and intellectual product of the early Americas, and students and teachers will now have full access to it because of this project."