The Getty Presents Anatomy & Art from the Renaissance to Today

Detail from Third Vision from Mirrors of the Microcosm. Lucas Kilian after Johann Remmelin. Engraving in Johann Remmelin, Catoptrum microcosmicum (Augsburg, 1619).

Los Angeles – For centuries, artists and scientists have been fascinated by the structures of the human body. Featuring works of art from the 16th century to today, the Getty Research Institute exhibition Flesh and Bones: The Art of Anatomy explores the theme of anatomy and art and the impact of anatomy on the study of art.

“Flesh and Bones celebrates the connection between art and science and the role of art in learning,” said Mary Miller, director of the Getty Research Institute. “This exhibition draws on the Getty Research Institute’s rich and varied holdings to tell the story of two disciplines that have long been intertwined. I believe visitors will find meaningful connections with the way artists and scientists have inspired one another for centuries.”

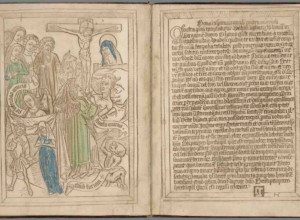

From spectacular life-size illustrations to delicate paper flaps that lift to reveal the body's interior, the body is represented through a range of media. In Europe, the first printed anatomical atlases, introduced during the Renaissance, provided new visual maps to the body, often composed of striking images. Landmarks of anatomical illustration such as the revolutionary publications of Vesalius in the 16th century and Albinus in the 18th century are represented as well as little-known rarities such as a pocket-size book of anatomy for artists from over 200 years ago.

The exhibition, which explores important trends in the depiction of human anatomy and reflects the shared interest in the structure of human body by medical practitioners and artists, is organized by six themes: Anatomy for Artists; Anatomy and the Antique; Lifesize; Surface Anatomy; Three Dimensionality, and The Living Dead. The last looks at the motif of the representation of the dead as living, with skeletons and anatomized cadavers capable of motion rather than inert on a dissecting table.

“Artists not only helped create these images but were part of the market for them, as anatomy was a basic component of artistic training for centuries,” said exhibition curator Monique Kornell. “Featuring selections from the GRI’s impressive collection of anatomy books for artists as well as prints, drawings, and other works, this exhibition looks at the shared vocabulary of anatomical images and at the different methods used to reveal the body through a wide range of media, from woodcut to neon.”

For artists of the modern era, anatomy is often a medium of expression and a signifier of the body itself, rather than purely an object of study. Robert Rauschenberg’s Booster (1967) and Tavares Strachan’s Robert (2018) are two life-size anatomical portraits as well as symbols of the passing nature of life. Echoing the composite prints of Antonio Cattani’s remarkable life-size anatomical figures from the 1700s in the exhibition, Booster is a fractured self-portrait based on X-rays of the artist that have been joined together.

Strachan’s Robert is not an exact likeness of the man it immortalizes, Major Robert Henry Lawrence Jr., the first African American astronaut, who tragically died in a training accident. In choosing to represent the hidden interior of the body in neon and glass, Strachan, a former GRI artist in residence, makes visible the unique history of Lawrence, while demonstrating an inner structure that equalizes all people.

Anatomists and artists have approached the problem of how best to describe the body’s complex and invisible interior with a variety of representational strategies, ranging from the graphic to the sculptural and, recently, the virtual. From paper-flap constructions that allow viewers to lift and peer under layers of flesh to stereoscopic photographs that mimic binocular perception and project anatomical structures into space, three-dimensionality was inventively pursued in the pre-digital age to cultivate an understanding of anatomy as a synthetic whole.

The exhibition is curated by Monique Kornell, guest curator; guest assistant professor, Program in the History of Medicine, Cedars-Sinai Hospital, Los Angeles, and is accompanied by the richly illustrated publication Flesh and Bones: The Art of Anatomy, edited by Kornell and published by the Getty Research Institute.