19th Century Silhouette Portrait Album Reveals Hundreds of Identities

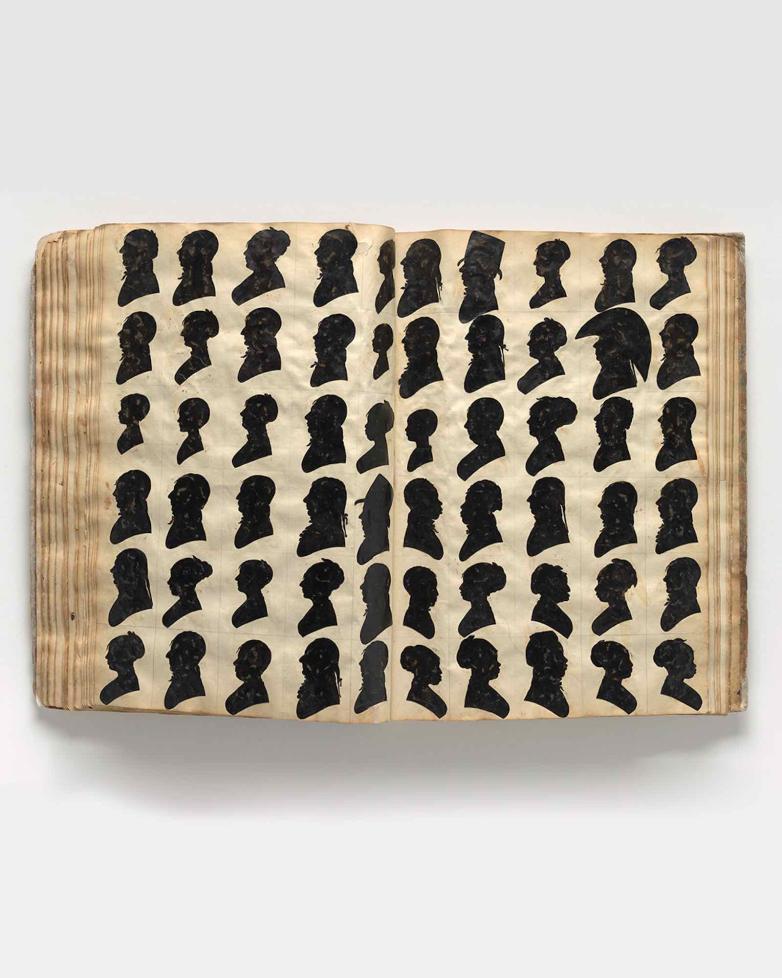

Page spread from William Bache’s Silhouettes Album, black paper coated silhouettes mounted on paper. Digitized by Mark Gulezian/NPG.

The Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery has announced the launch of William Bache’s Silhouettes Album, a microsite featuring new research and digitized images for 1,800 cut-paper silhouettes by Anglo-American artist William Bache.

In addition to presenting portraits of famous figures like Thomas Jefferson and Martha Washington, the digital project restores the identity of previously unknown individuals rarely encountered in Federal-era portraiture, from traveling entertainers to tavern keepers and dance instructors.

Funded by Getty through its Paper Project initiative, the digital platform features hi-res images, a biography and interactive timeline of Bache’s life, conservation reports, and more for this important example of one of the most affordable forms of portraiture in early United States history.

In 2008, Smithsonian conservators discovered the fragile papers of the Bache album contained arsenic and could not be safely handled or displayed without special precautions. The National Portrait Gallery used Getty’s support to overcome these limitations by fully digitizing the entire volume. The lead curator also completed extensive research that confirms the identities of hundreds of sitters in New Orleans and has generated a new understanding of traveling portrait artists at the turn of the 19th century.

“Although the Portrait Gallery has owned this album of silhouettes for over 20 years, it took the support of Getty and the digital resources that are now available to finally unlock its secrets,” says Robyn Asleson, curator of prints and drawings at the National Portrait Gallery. “Digging deeply into the circumstances of the album has shed fascinating new light on the artistic practice of William Bache and has yielded a few surprises, such as his extraordinary mobility in pursuit of new markets and his extensive use of advertising to promote himself.”

Asleson and a research assistant scanned through Ancestry.com, digitized newspapers, history books, baptismal records, wills, and other legal documents to unveil the identity of sitters, including many of Afro Caribbean descent for whom no other likeness is known to exist. Users of the microsite can now “flip” through pages of the album and click on hi-res images of each portrait to learn the sitter’s full name, lifespan or years active, and the date their portrait was created.

Another major discovery came when Asleson expanded her research to Spanish-language materials, which verified Bache worked in Cuba producing portraits in a largely untapped market. The revelation helped Asleson confirm that approximately 1,000 silhouettes in the album were made in the Caribbean, from Catholic priests wearing birettas to sitters of African heritage.

Affordability was key to Bache’s success, as contemporary newspaper ads digitized on the microsite tout “four correct profiles for 25 cents”, today’s equivalent of approximately five dollars. The low price enabled a greater range of social classes to purchase these keepsakes compared to costlier forms of portraiture like painting or sculpture.

The microsite’s interactive timeline presents Bache’s biography in great detail, from his immigration to Philadelphia to his successful career creating silhouette portraits without formal training, traveling from town to town to provide his services. He produced striking likenesses of his sitters by using a unique type of physiognotrace, a mechanical device Bache patented in 1803 with his partners Augustus Day and Isaac Todd.

Bache’s business savvy is also evident in his decision to set up shop in New Orleans just after Louisiana became a U.S. territory and was booming from the sugar trade. His nearly 700 portraits in New Orleans showcased the extraordinary internationalism of the city at the time, with sitters of French, Spanish, German, British, and Caribbean descent.

“Understudied works on paper like the Bache album exist in many museum and archival collections, and Asleson’s project represents exactly the kind of curatorial ingenuity that Getty seeks to support in our Paper Project initiative,” says Heather MacDonald, senior program officer at the Getty Foundation who manages this grant program. “It’s a common human experience to wonder about our ancestors, and the Bache microsite can convert this curiosity into new discoveries.”