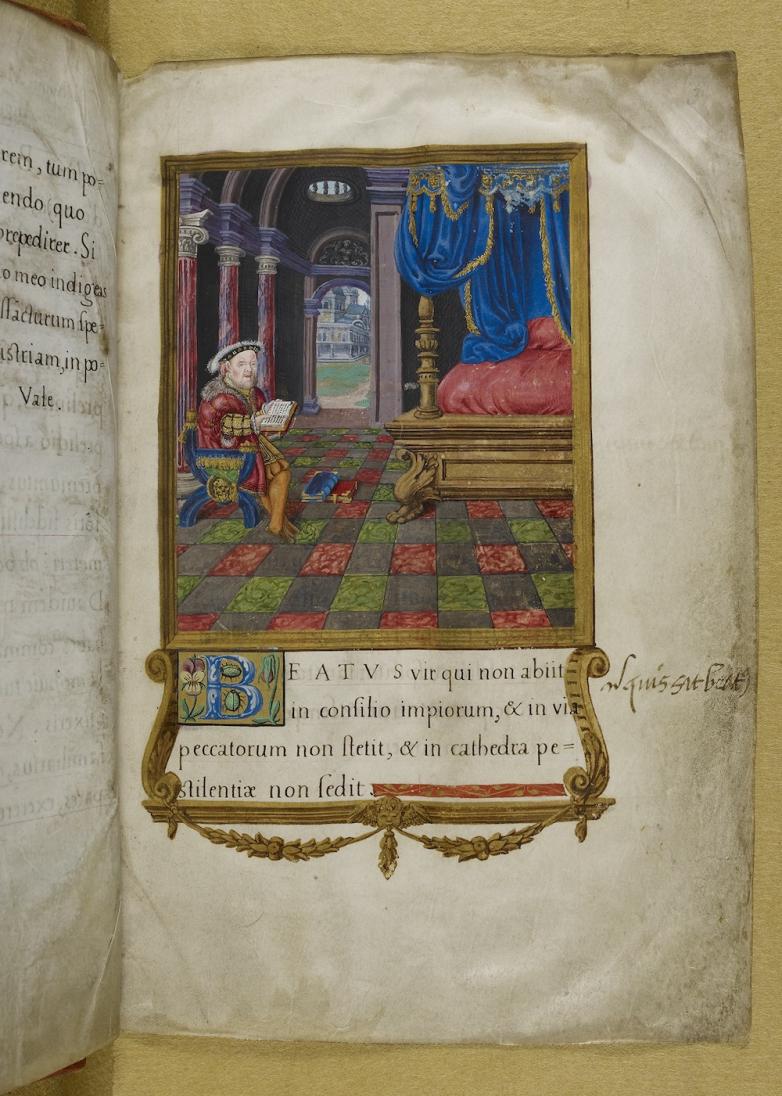

The Psalter of Henry VIII (1540, pictured at left). This tempera on parchment prayerbook, with miniatures by the French artist Jean Mallard, was used by the king himself—it even features his handwritten annotations.

Two Bibles are highlighted: The Coverdale Bible, printed in 1535, with title page designed by Hans Holbein the Younger, and The Great Bible of 1540, printed on vellum, with title page attributed to Lucas Horenbout; the hand-tinted and parchment-printed edition on view was owned by Henry VIII.

Instruction of a Christen Woman by Juan Luis Vives was printed in London in 1557. Was this one of Queen Elizabeth I’s favorites? According to the Met, it was originally written in Latin for the young princess Mary.

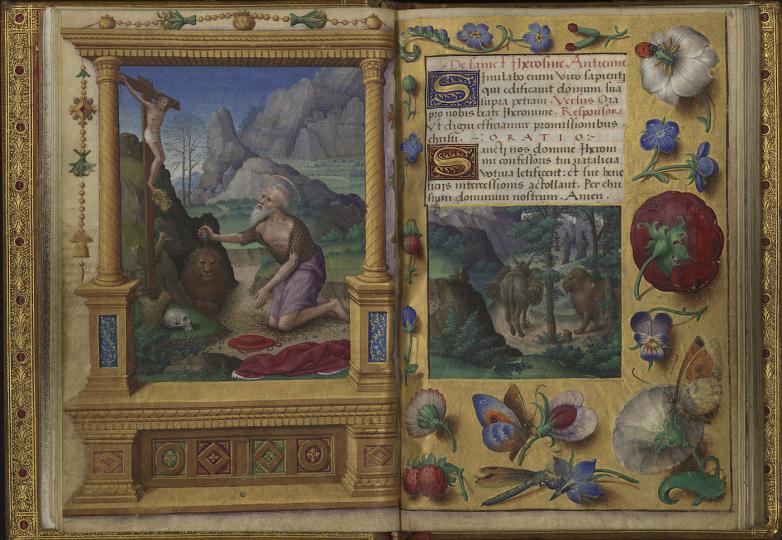

“Tabula Cebetis, and De Mortis Effectibus,” a 1507 scholarly manuscript transcribed by an Italian friar, was meant to be a gift for Henry VII.

“Octonaries Upon the Vanitie and Inconstancie of the World,” ca. 1600, is an ink and watercolor manuscript made by a woman, Esther Inglis (French or British), who transcribed and painted devotional texts.

The First and Chief Groundes of Architecture Used in All the Auncient and Famous Monymentes (1563) by John Shute is the first architectural treatise printed in English. Shute wrote it at the request of King Edward VI, but it was published during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I.