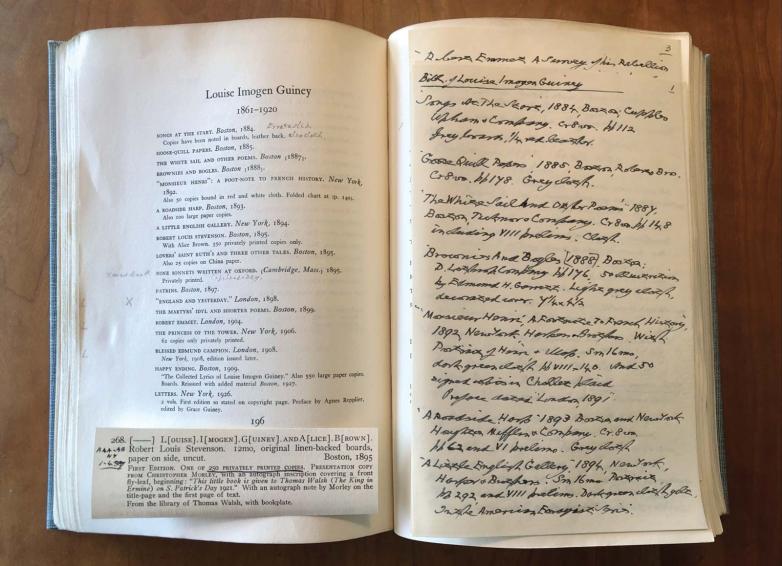

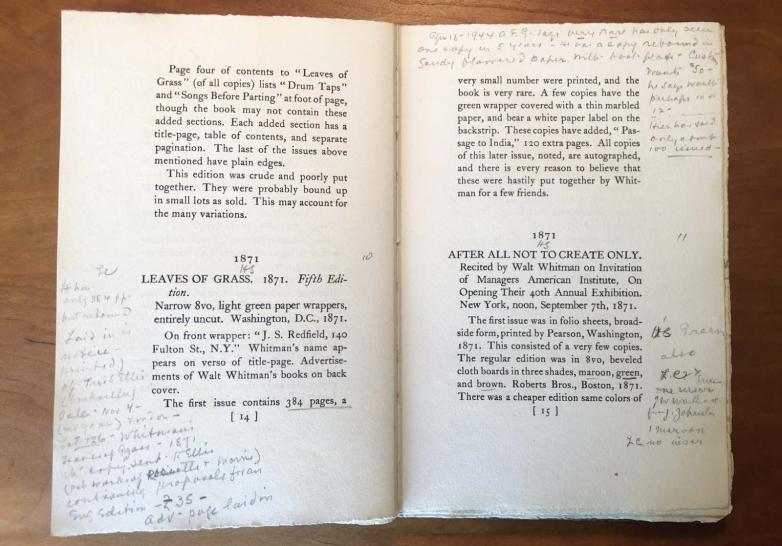

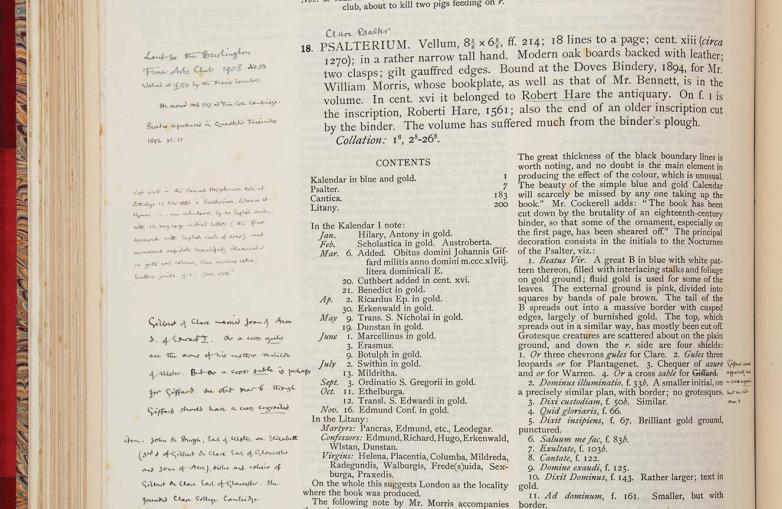

For most collectors of previous generations, books with extensive manuscript notes of earlier owners were viewed as defects, unless the particular copy could be connected with someone who was famous. Though this is still the case for most books of the recent past that contain highlighting, underlining, or marginalia, I hope that bibliographical works can be viewed differently by collectors. Outside of institutional collections, the market for these books has always been relatively small, and for those interested in the subject, the work of any owner of a bibliography or catalogue who has gone to the trouble of selecting and acquiring the book, and then writing or inserting other material in it, deserves our attention, even if we’re not able to determine their identity.

Annotated author’s copies of books in all subjects, including reference works, have long been sought after and collected, but beyond these particular copies, there are many other interesting copies that appear on the market that are worth seeking out and adding to our collections. In some instances, the marginalia of an author or other owner/annotator have been preserved when that particular copy served as the basis for a reprint.

Examples include Frederick A. Goff’s Incunabula in American Libraries: A Third Census of Fifteenth-Century Books Recorded in North American Collections (Millwood, New York: The Bibliographical Society of America and Kraus Reprint Corporation, 1972); Bibliographie d’éditions originales et rares d’auteurs français des XVe, XVIe, XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles, contenant environ 6,000 fac-similés de titres et de gravures by Avenir and Stéphane Tchemerzine (Paris: Hermann, 1977), with annotations by French bookseller Lucien Scheler; and the lithographic reprint of the first eight volumes of Catalogue of Books Printed in the XVth Century Now in the British Museum (London: The British Museum, 1963), which reproduced the British Museum’s working copy, which contained annotations by many individuals, principally bibliographer Victor Scholderer.

The marginal notes made by the owners of bibliographical works usually survive as long as the books exist, though they may not be studied unless the annotator is known and is considered to be someone with knowledge of the field. But even when the identity of the annotator can’t be determined, these notes and markings can reveal additional information that isn’t recorded elsewhere, and while not all such notes are illuminating or even accurate, examining them closely is often worthwhile.