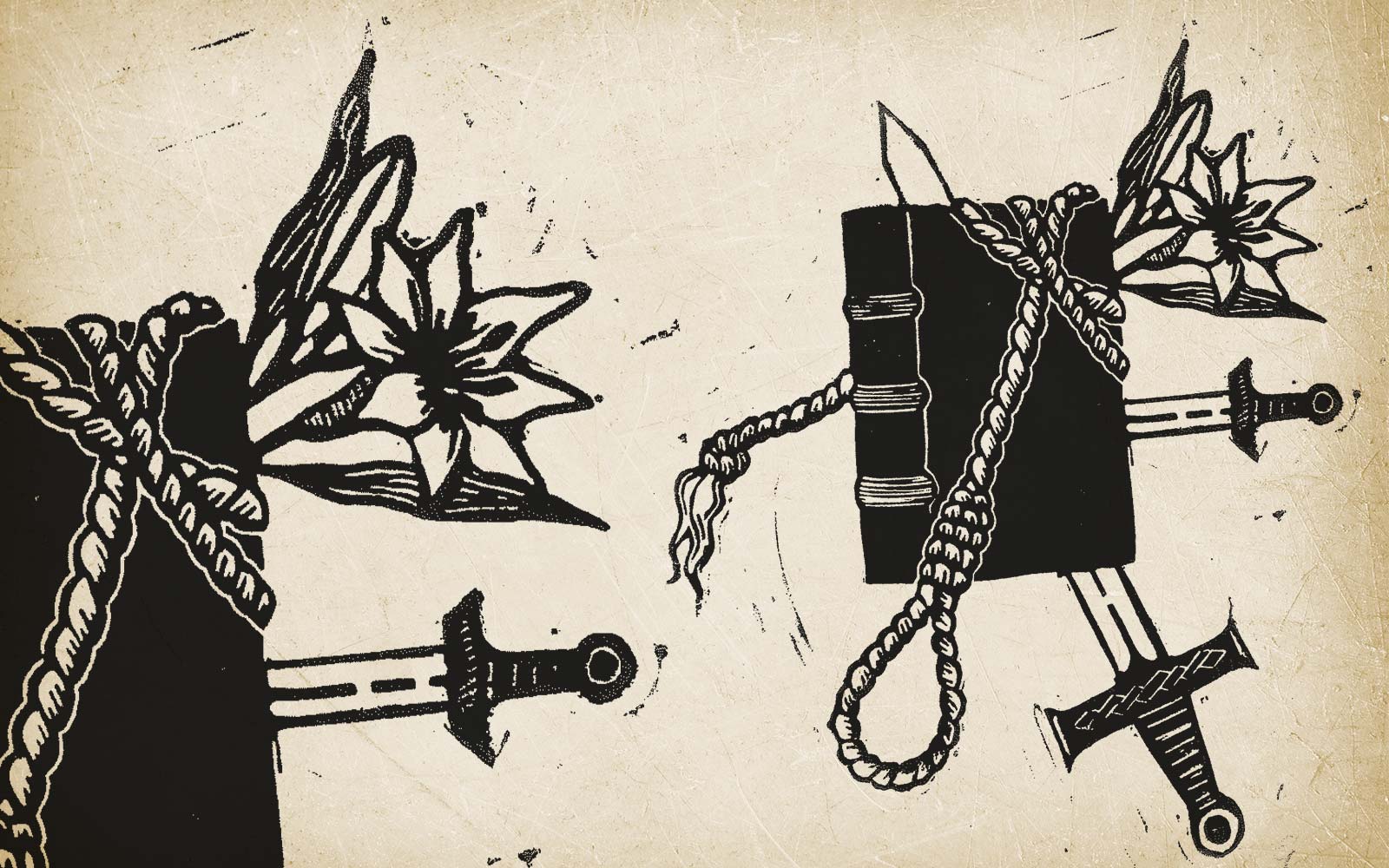

A rather more direct curse is the only one included in Book Curses without a named manuscript reference. The last known sighting of it was at a 1962 Sotheby’s auction, where its sale description recorded a Middle English book curse:

He who steals this book,

Shall be hanged upon a hook,

Behind the kitchen door.

The title Book Curses is actually a little misleading, said Baker, as some of the curses are inscribed on stone tablets from the ancient Near East, while others are on documents. “The vast majority of the curses that appear in books are handwritten, but they appear later in the form of bookplates, which could be easily reproduced and pasted into the flyleaves of a book. They also still prove popular today—artists on crafting websites sell bookplates with curses preprinted for you to stick into your own books.”

Baker has her own crafting take on the subject, teaching herself linocutting during the COVID-19 lockdowns and using book curses as inspiration.

“Having spent a lot of time with late medieval manuscripts and incunabula, I was particularly drawn to imitating the qualities of illustration of wood-block prints,” she said. “I find it fun to try and imagine the individuals who were motivated to inscribe the curses, from Assyrian rulers to early modern cooks and naughty Victorian schoolchildren.”