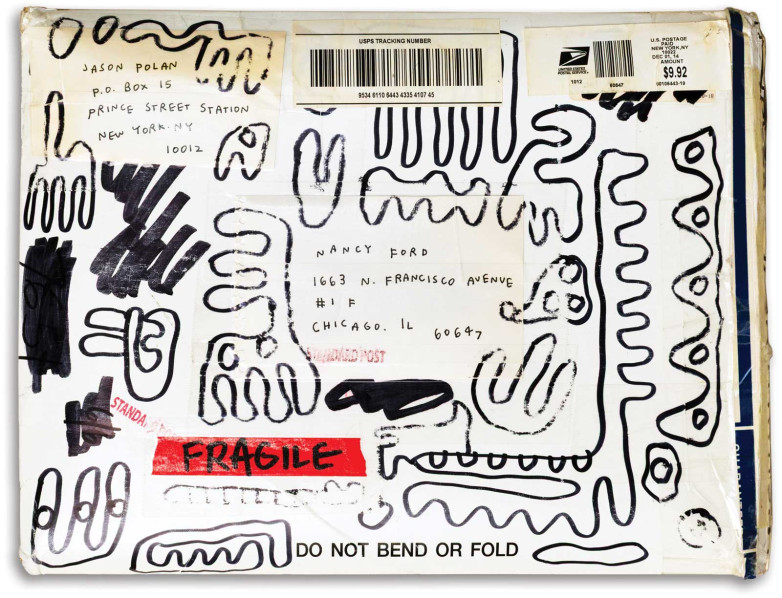

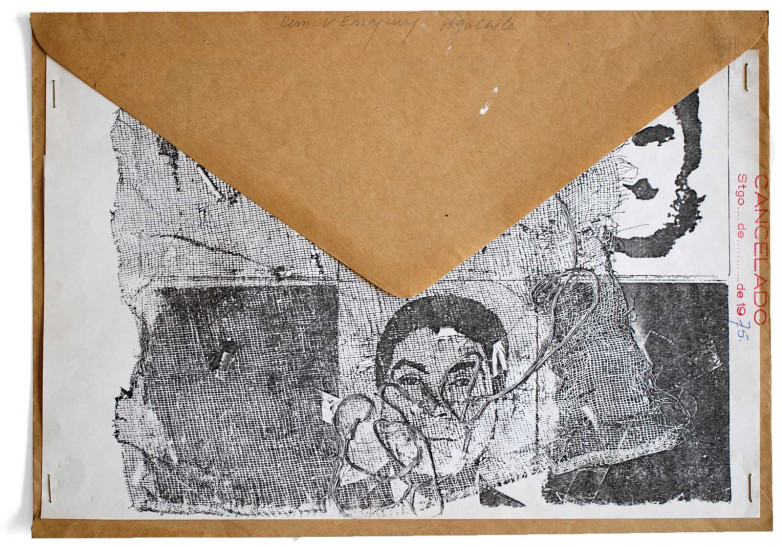

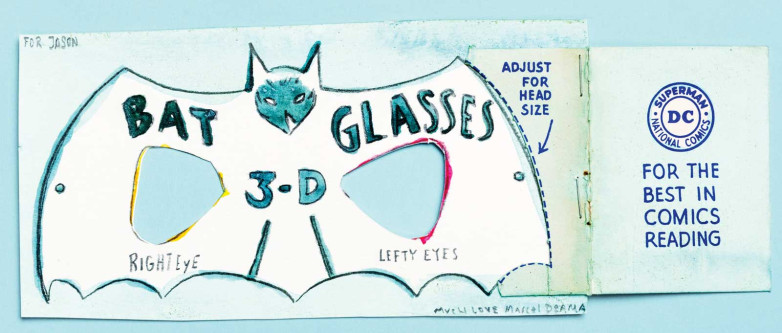

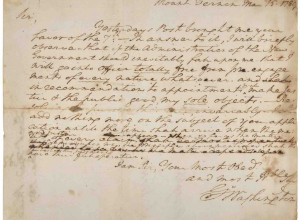

As long as humans employ courier services, from pigeons to state-maintained networks, artists harness these systems for their work. The earliest piece of mail art may be lost to history (some argue Cleopatra’s ingenious rug delivery to the Roman emperor was the genesis; others wait for Ray Johnson and a group of 1960s late-modernists to establish the “New York Correspondence School” with self-aware intention). Still, recent exhibitions, new publications, and collections remind us that mail can be utilized for unexpected creative ends.

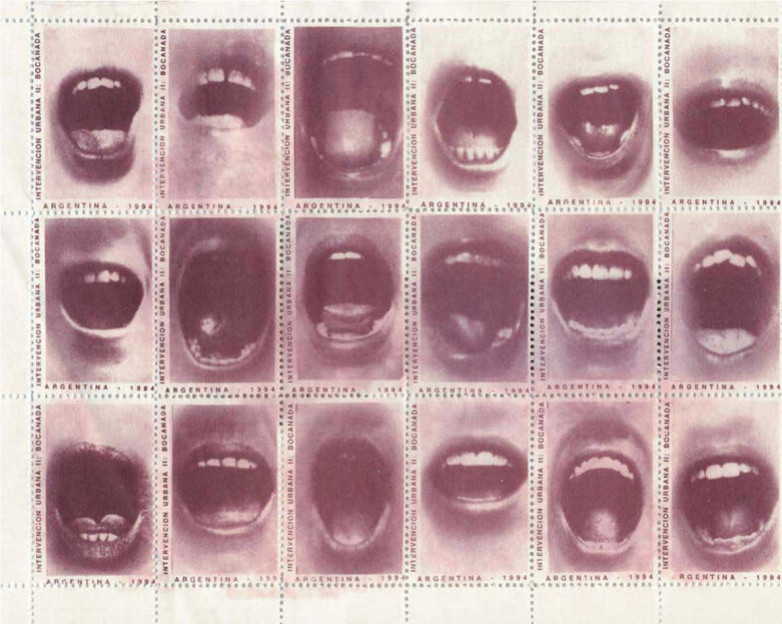

While visual artists long dashed off a sketch on a letter, it wasn’t until the early twentieth century that anti-establishment artists intentionally incorporated mail into a practice, such as Duchamp’s nonsensical postcards and Kurt Schwitters’s use of discarded envelopes and postage stamps in collages. With these precedents, artists in the 1960s built an international mail art network and what became known as the Mail Art Movement.