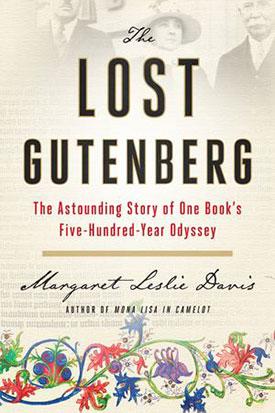

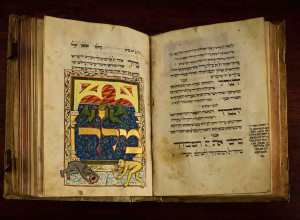

The Gutenberg Bible really is the Holy Grail of rare books -- less than fifty are known to exist, in various states of completeness, and none are available to buy. The one Davis follows is No. 45, a beautiful copy in a contemporary binding. (So beautiful, in fact, that some color photography, if only of the bible's first page with its green and gold illuminated initial, would have been nice. At least Davis points us to the virtual copy.) After some necessary preliminaries, her tale begins with the book's first known owner, Archibald Acheson, 3rd Earl of Gosford, who keeps the book in his Irish castle, and ends in a Japanese vault. Along the way, we meet a couple of English book collectors, but the longest stopover is with one American collector, Estelle Doheny, the "Mighty Woman Book Hunter." Hers is a tale of triumph and betrayal; as a profile of Doheny alone, Davis' book is worth the price of admission.

The Gutenberg Bible is neither the world's oldest book, nor the first use of moveable type, as is sometimes said in shorthand, and Davis, who is not a rare book world "insider," is well aware of that. Her reporting is spot-on, and her style is lively and engaging. A quibbler might question the use of the present tense throughout, but overall, an admirable achievement. (Read a sample here.)