Online Getty Exhibition Explores Palmyra in English and Arabic

Temple of Baalshamin, Louis Vignes, 1864. Albumen print.

Los Angeles – For centuries the ruins of the ancient city of Palmyra have captured the imagination– testaments to the legacy of the prosperous multicultural center of trade that once dominated the region. Online beginning February 3, Return to Palmyra, presented in English and Arabic, invites audiences to explore the rich history of the city, including an exhibition of rare 18th-century etchings and 19th-century photographs of the site, new scholarship, and a moving interview with Waleed Khaled al-As’ad about the modern-day experience of living and working among the ruins of this storied locale.

With the help of a committee of Arabic scholars and specialists, this born-digital exhibition looks at Palmyra from a regional perspective.

“European and American artists and scholars have often approached Palmyra’s compelling, unique history from a western perspective,” says Mary Miller, director of the Getty Research Institute. “Return to Palmyra aims to be completely new and different, and equally compelling in both Arabic and English.”

Return to Palmyra re-presents the Getty’s first online exhibition, The Legacy of Ancient Palmyra, which launched in 2017, with updated technology, new texts, and a classical Arabic translation.

The new texts include a detailed local history of Palmyra by prominent scholar Joan Aruz, Curator Emerita of Ancient Near Eastern Art at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. The site also includes a powerful and moving interview with Waleed Khaled al-As’ad, former Director of Antiquities and Museums at Palmyra. He describes his experience growing up among the ruins under the mentorship of his esteemed father Khaled al-As’ad, who was the Director of Antiquities and Museums at Palmyra for 40 years until he was killed by ISIS while defending the cultural heritage of Palmyra.

“Return to Palmyra presents ancient issues but is also very relevant and topical in today’s world as Palmyra and the monuments in this region continue to be a flashpoint on the world stage,” said Frances Terpak, curator and head of photographs at the Getty Research Institute, who curated the exhibition. “It is important to bring global attention to the fragile state of this historic site and its once-thriving community and the needs of the people who still live there as well as those who hope to someday return.”

A team of five Arabic scholars and specialists consulted at each step in the process to provide a reading and viewing experience that is consistent and engaging in both languages. One of the scholars, Ridha Moumni, Aga Khan fellow at Harvard University, conducted field work in Palmyra for his dissertation research. As Moumni relates “experiencing the overwhelming beauty of this great caravan city lingers in one’s memory. As a crossroads of cultures, it generated a distinctive building style and decorative aesthetic that harbored a diverse society in the Near Eastern desert over the centuries.”

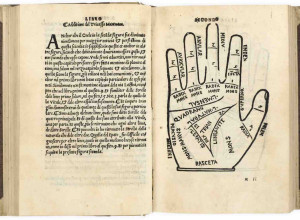

At its pinnacle in the mid-2nd to 3rd century CE, Palmyra was a wealthy oasis metropolis, a multiethnic center of culture and trade on the edge of the Roman and Parthian empires. Stretching about three kilometers across the Tadmurean desert, the ruins of Palmyra are striking markers of the city’s place in history. Starting in the late-17th century, Western explorers encountered these ruins and transmitted knowledge about the site through written descriptions, transcriptions of the numerous Palmyrene inscriptions scattered through the ruins, the collecting of ancient Palmyrene art and artifacts, illustrations, and, later, photography. Return to Palmyra features engraved illustrations from the 18th century by the architect Louis-François Cassas (French, 1756-1827) and the first photographs of the ruins taken by Louis Vignes (French, 1831–96) in 1864.

In 1784 French artist and architect Louis-François Cassas traveled to the Eastern Mediterranean as part of a diplomatic mission to the Ottoman court. Arriving in Palmyra in May 1785, Cassas assiduously worked to record the immense quantity of ruins scattered across the landscape until departing a month later with a caravan of 500 camels heading on to Baalbek in modern-day Lebanon. His panoramic etchings invite the viewer to simultaneously marvel at the grandeur of antiquity and lament its inevitable decay. An amalgamation of orientalism and antiquarianism, the prints made from his drawings show local Bedouins inhabiting a dramatic landscape strewn with antique blocks, Corinthian columns, and monumental doorways. His primary objective to systematically record the artistry and ingenuity of a vanished civilization is evident from Cassas’ numerous technical renderings of the imposing civic and religious architecture. Floor plans and reconstructed architectural elevations are complemented by details of ornamental features.

Eighty years later, in 1864, naval lieutenant Louis Vignes went to Palmyra, where he took over 30 photographs, including three-part panoramas of the ruins. Until their acquisition in 2015 by the Getty Research Institute, the Palmyra photographs featured in this exhibition were largely unknown because they had remained in the possession of the Luynes family. Printed by Vignes’ teacher, the artist and photographer Charles Nègre, probably soon after Vignes' return, these three dozen photographs of Palmyra are extremely rare and, in some cases, unique prints. They are the earliest known photographic images of the ruins, making Vignes the first to aim the camera's lens on the monuments. Produced some 75 years after Cassas' engravings, these pioneering photographs of Palmyra complement the prints to create an unparalleled visual record of this extraordinary ancient site.

Furthering the Getty’s commitment to its Open Content Program, most of these remarkable images are available to digitally share, adapt, and repurpose through a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY).