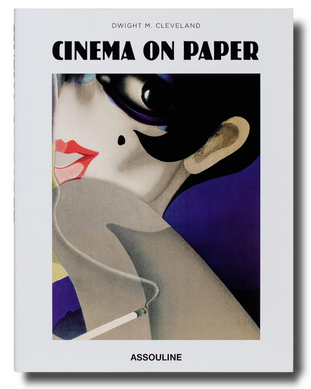

A real estate developer and historic preservationist based in Chicago, Dwight Cleveland has been collecting movie posters for more than forty years—during which he assembled what is believed to be the largest privately held and fully curated film poster archive in history, comprising more than 45,000 works. After deaccessioning this archive in 2016, Cleveland now retains personal holdings of approximately 4,750 posters, lobby cards, and “coming attraction” glass slides, the vast majority of which are unique or one of just a few works from across the scope of film history. Together with the collection’s recent showcase at the Norton Museum, the publication of Cinema on Paper offers an unprecedented look at some of the most visually engaging and historically significant works from these holdings, providing an opportunity to reconsider these promotional objects as a popular art form unto themselves—one that distinctively tracks the cultural, historical, and artistic developments of the twentieth century.

The first book ever released by Assouline to focus on film posters, Cinema on Paper includes a foreword by Turner Classic Movies Primetime Host Ben Mankiewicz (grandson of Citizen Kane screenwriter Joseph Mankiewicz), as well as an introduction by former New York Times Book Review Editor and noted design scholar Steven Heller. Mankiewicz’s essay notes that “[m]ovie posters represent what is perhaps the purest collision of art and commerce ... they are imbued with optimism and filled with the escapist thrill of what we imagine the screen holds in store for us: romance, adventure, laughter, betrayal, tragedy, justice, redemption, truth.”

The publication reproduces more than one hundred works from Cleveland’s collection, including promotions for such iconic Hollywood classics as King Kong, Casablanca, The Godfather, and 2001: A Space Odyssey, as well as more obscure works such as the 1958 teen exploitation film High School Hellcats. Several of the American movie posters featured in the book appear alongside European or Asian editions advertising the same film, highlighting the collection’s geographic breadth and inviting readers to reflect on diverse visual approaches to movie marketing across cultural contexts. As mass- produced objects of popular art drawn from nearly every decade of the twentieth century, each poster in the collection provides a distinctive snapshot of the historical and social conditions from which it originated.

The works featured in Cinema on Paper encompass nearly one hundred years of film distribution, from posters featured in 1910s Paris through the release of the American independent film Secretary in 2002. The book includes several works that are believed to be the only extant copies in existence, including a large-scale German-language advertisement for the Oscar-winning film Grand Hotel (1932); a title card from the late silent-era classic Manhattan Cocktail (1928), directed by Dorothy Arzner; a lobby card from Hallelujah! (1929), the first African American film released by a major studio; and a lobby-card portrait of a reclining Nazimova from Oscar Wilde's scandalous Salomé (1922), which was made byan exclusively gay and lesbian cast and crew. These images are accompanied by contextual annotations that invite readers to evaluate them not as promotional objects but as freestanding works of graphic art.

“Though movie posters may serve a commercial purpose, I firmly believe that they deserve to be studied, experienced, and celebrated as an art form in their own right—at their best distilling the very soul of the movies they promote into a single, indelible image,” said Cleveland. “I hope that by making my collection accessible to a wider audience through this book and exhibition— both exceptionally well assembled by my partners at Assouline and the Norton, respectively— that I can inspire others to look more deeply at what might seem like disposable advertising products and recognize them instead as a distinguished form of popular art.”