James Joyce, born in 1881, the same year as Virginia Woolf, was educated at a range of elite educational establishments, including Clongowes Wood College, a Jesuit boarding school, and University College Dublin, where he took a BA in modern languages, graduating in 1902. He wrote Ulysses between 1914 and 1921 in Trieste, Zurich, and Paris. During this period women were struggling on several fronts: struggling to acquire the right to vote; struggling to be taken seriously in the world of work; struggling to control their fertility; and, very often, struggling to gain access to the kind of education from which Joyce and many of his male peers benefitted. Any woman who became confident and active in the public sphere during this era did so in face of cultural forces that would have preferred they stay silent, largely out of sight, and ensconced in the domestic sphere. This is why we need to take the achievements of the women who enabled Ulysses seriously.

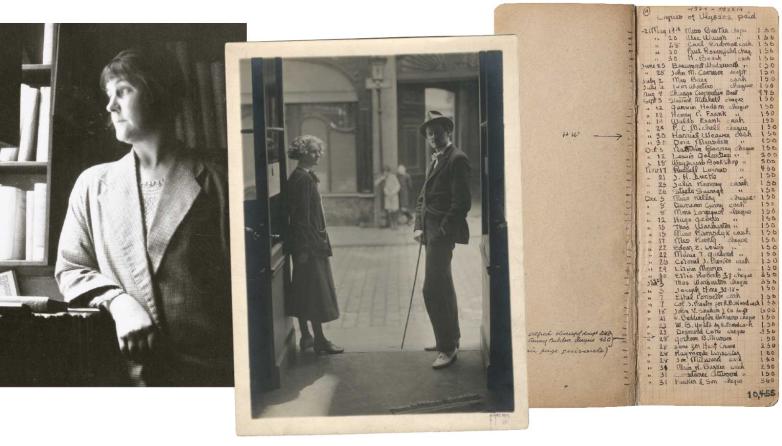

Certainly there were men who enabled Joyce too. Ezra Pound was practical and tireless in his advocacy of Joyce’s genius, and John Quinn, New York lawyer and patron of the arts, helped Joyce financially by arranging to purchase the manuscript of Ulysses long before the work was finished. But women played a crucial and formative role in enabling Joyce to create and realize Ulysses. Harriet Shaw Weaver (1876–1961) became acquainted with Joyce’s work in 1914, when The Egoist, the London periodical she edited, committed to the serialization of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.

In due course, Weaver would become Joyce’s most loyal and important supporter. Faced with the hostility of London publishers to Joyce’s sexual candor, Weaver turned publisher and issued the first British editions of both Portrait (in 1916) and Ulysses (in 1922). From 1916, she gave Joyce significant sums of capital to enable him to commit to writing full time. By 1923, she had given him investments in the London stock exchange valued at £22,850, equivalent to about £1.3 or $1.7 million in today’s terms. This ensured Joyce’s steady income, as documents on display demonstrate.

Like Weaver, Sylvia Beach supported Joyce financially and as publisher of Ulysses. She gave him an astonishing 66 percent of the net profits on the first edition, and she quietly paid the enormous printing bill incurred by dint of the copious revision and extension to the text that Joyce made to Ulysses when it was in proof. Her tiny notebook, in which she meticulously recorded subscriptions for the first edition, is on display, and serves as a potent reminder of her careful labor behind the scenes.