Lionizing the Bestiary

Fantastic medieval beasts are on display at the Getty

Bestiaries, allegorical texts with pages of illuminated animals—some real, like the lion, some mythical, like the griffin—were the bestsellers of their day. Until now, there has been no more comprehensive look at this medieval megahit than Book of Beasts: The Bestiary in the Medieval World at the Getty Center in Los Angeles through August 18. This exhibition brings together for the first time twenty-four of a known sixty-five illuminated Latin bestiaries. Roughly twenty-three hail from the UK, with sixteen of them traveling for the first time since the Middle Ages.

Based on the Physiologus, a natural history text written by an anonymous Christian author contemporaneous with the Greeks, bestiaries drew cues from the work of sixth-century scholar Isidore of Seville’s Etymologies. It hit its peak of popularity in the thirteenth century and persisted for another three hundred years.

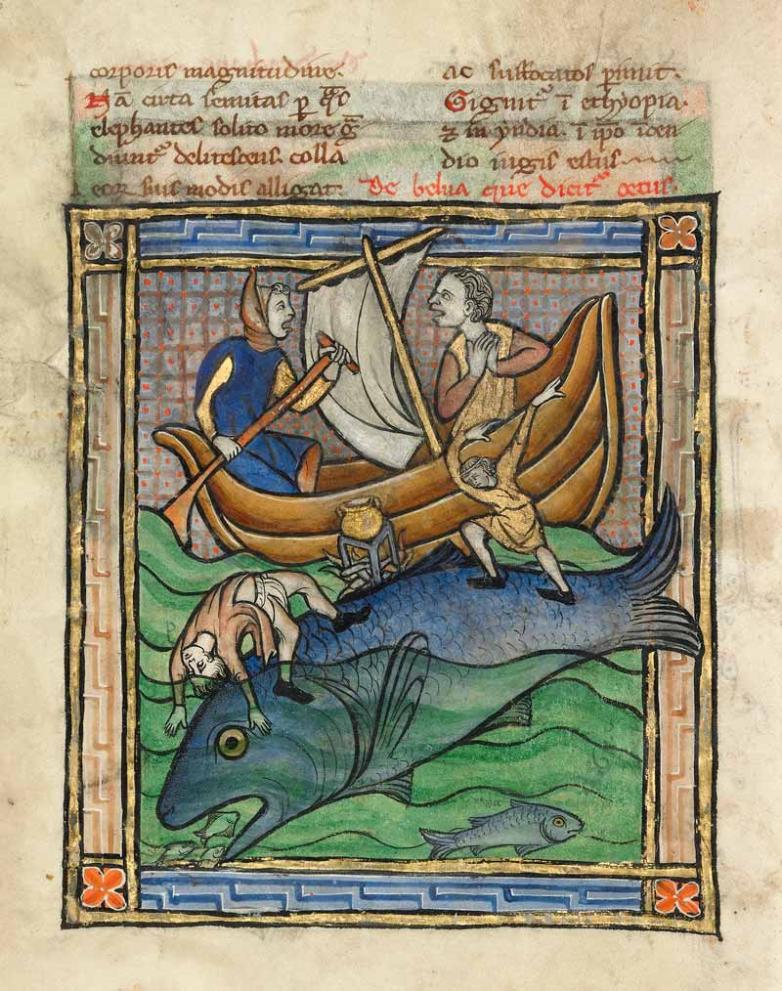

Credit: The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Ms. Ludwig XV 3, fol. 89v.

Painted with gold leaf and tempera pigment on parchment by anonymous craftsmen and itinerant artisans, each manuscript is a variation on what came before, depicting the same animals and stories and emphasizing the divine hand in the design of the natural universe. Each is also a singular work of art in its own right, once occupying shelf space in well-appointed homes of noblemen throughout France and Germany, but mainly England.

Broken down into five sections, the new show begins with the bestiary’s most recognizable creature and one that has endured to today—the unicorn. It is often depicted being lured into a trap, baited by a pure maiden in whose lap it rests its head. In a moment of distraction, its side is pierced by the spear of a waiting hunter, suggesting the crucifixion, a persistent theme in the genre.

“The word ‘atheist’ didn’t even exist in the Middle Ages. Christianity permeated every aspect of life in a pervasive way,” said senior curator Elizabeth Morrison as she set up the show’s second section, which focuses on the development of the book’s textual and visual tradition over the centuries. While the descriptions and religious allegorical elements remain consistent, their representations vary based on artistic interpretation.

In a section called “Beyond the Bestiary,” the book’s influence and legacy is revealed in similar manuscripts from the Arabic and Hebrew, with accompanying Aesop-like moral tales. “The animals developed into a visual language of their own, escaped from the pages of the manuscript into tapestries and metal work and even became the basis of natural history,” noted Morrison.

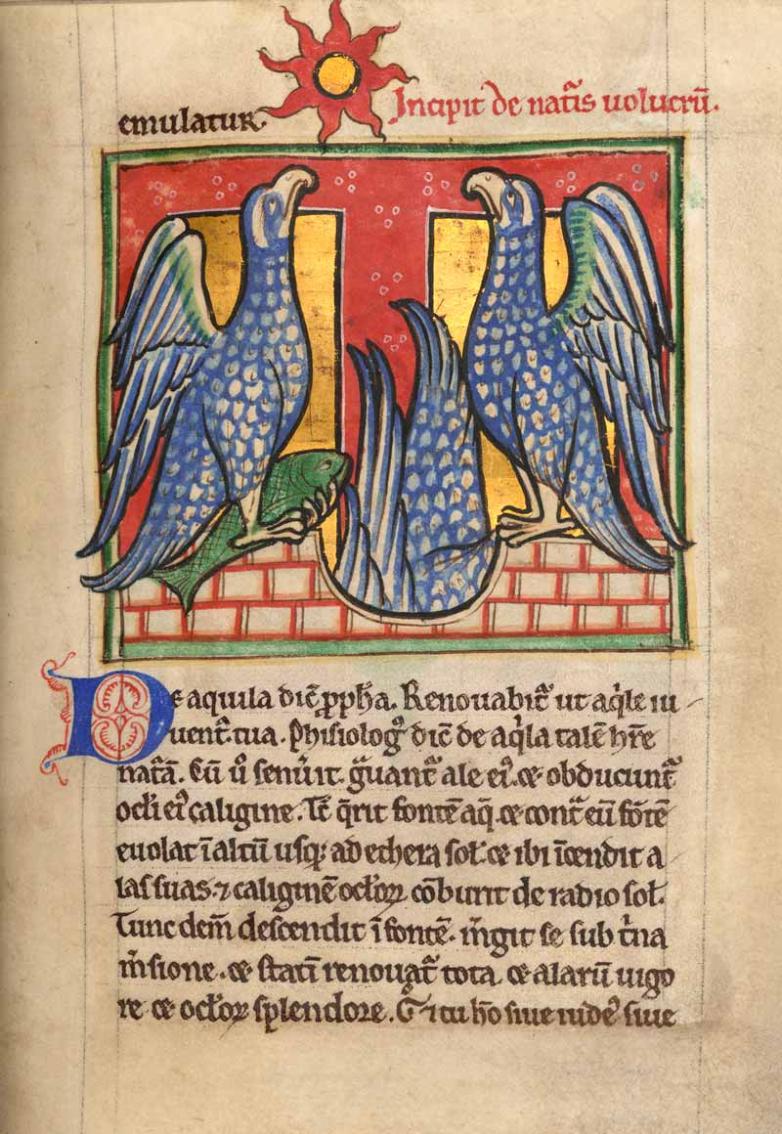

Credit: Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan in 1902

As Christian concepts became less associated with the animals, they assumed their own value as iconic images, taking a place in scholarly and encyclopedic texts. “We found it was a universal impulse to see human characteristics or lessons about the world in animals, and anthropomorphizing to make animals more relatable,” observed Larisa Grollemond, the assistant curator of manuscripts.

Grollemond was a driving force behind the show’s final section, which jumps forward to the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, when the bestiary experiences a mainly secular revival under the brush of artists like Jean Dupuy, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, and Pablo Picasso, as well as Raoul Dufy, who collaborated with poet Guillaume Apollinaire on Le Bestiaire (1911). “What's interesting is that they preserve the medieval balance of text and image. Still very illustrative, very image heavy. A lot of the time the text does have some sort of moral or lesson-telling function as the medieval text does,” said Grollemond.

It has taken six years to assemble Book of Beasts: The Bestiary in the Medieval World, mostly curated not from museums but libraries, whose remit is to preserve and make available for occasional reference, unlike a museum’s, which is to exhibit to the public. Shut away from light and dust, the pristine images are stunningly well preserved after centuries. “Some of them have 130 illuminations,” Morrison said, with a shake of her head. “And we get to show one, that’s it.”