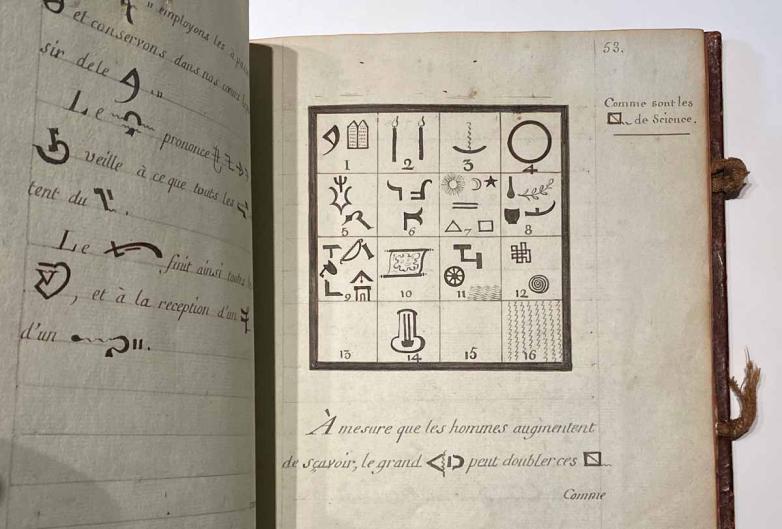

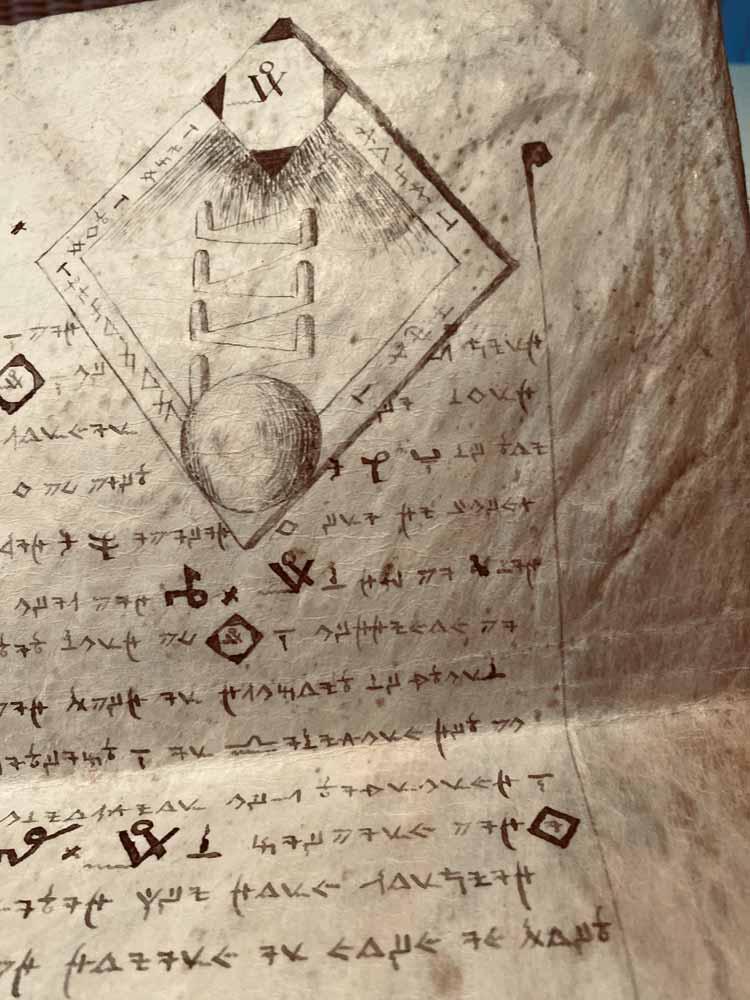

Merhige, a first-time filmmaker and recent graduate of SUNY Purchase at the time, was sent scrambling to find out what he meant. His investigation led him to Hermes Trismegistus, associated with the Greek god Hermes and Egyptian god Thoth and author of the “Corpus Hermeticum.” In it he espouses an understanding of the universe based on principles of astrology, alchemy, and theurgy that recognizes not a separation, but a merging of opposites resulting in transformation and transcendence. While sixteenth-century Dominican friar Giordano Bruno was responsible for resurrecting these ideas, they were consolidated under German philosopher Jakob Böhme whose first book, Aurora, appeared in 1612.

Böhme’s writing became the cornerstone of a collection that numbers roughly 2,400 volumes, many dealing with mysticism and Freemasonry, areas that subsequently captured Merhige’s interests.

“If everything emanated from this one deity, how do you reconcile evil with good? What Christianity was doing was separating it between heaven and hell. What Böhme does is he connects it all together,” said Merhige, who applies the same concepts when writing characters and directing actors. “It helps me understand that nothing is that simple, nothing is one thing. No character is good, entirely, and no character is entirely bad. And what Böhme trains the mind to do is understand that this is actually part of life and existence.”

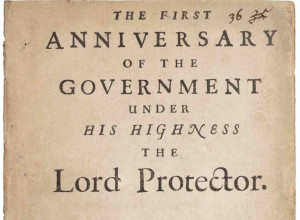

Merhige’s collection in his Beverly Hills townhouse includes subsequent titles by Böhme such as The Threefold Life of Man, Forty Questions on the Soul, and The Incarnation of Jesus Christ, along with a complete collection of the rest of his writings in their first English translations from the seventeenth century as well a second set of translations by William Law from the eighteenth century, a four-volume collection formerly belonging to the Earl of Cromer who served as consul general of Egypt from 1883–1907.