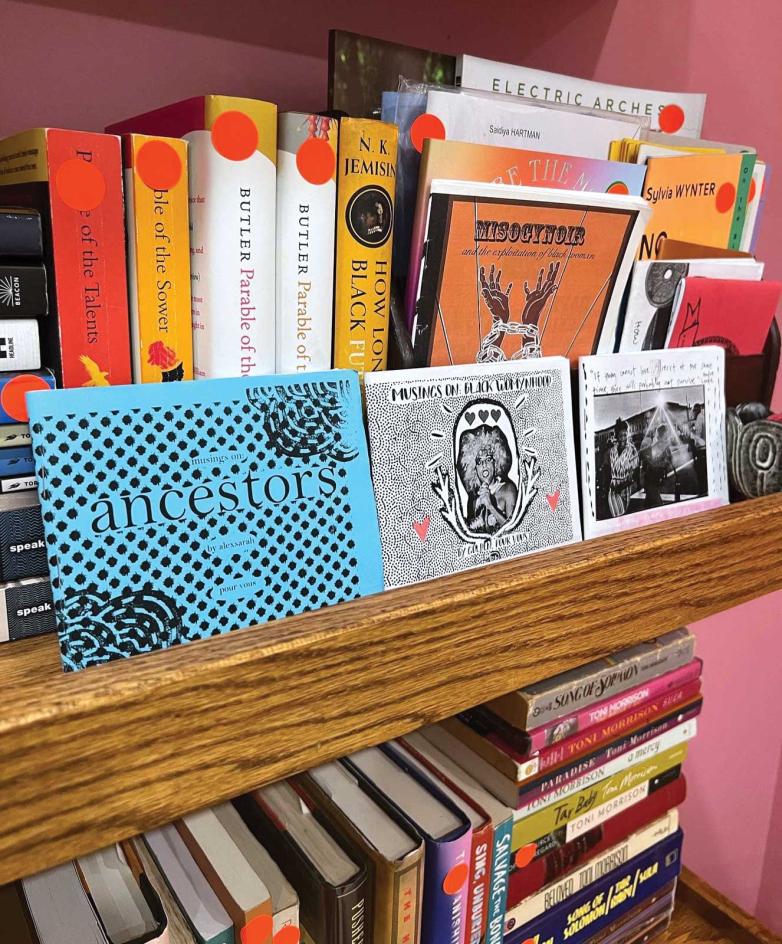

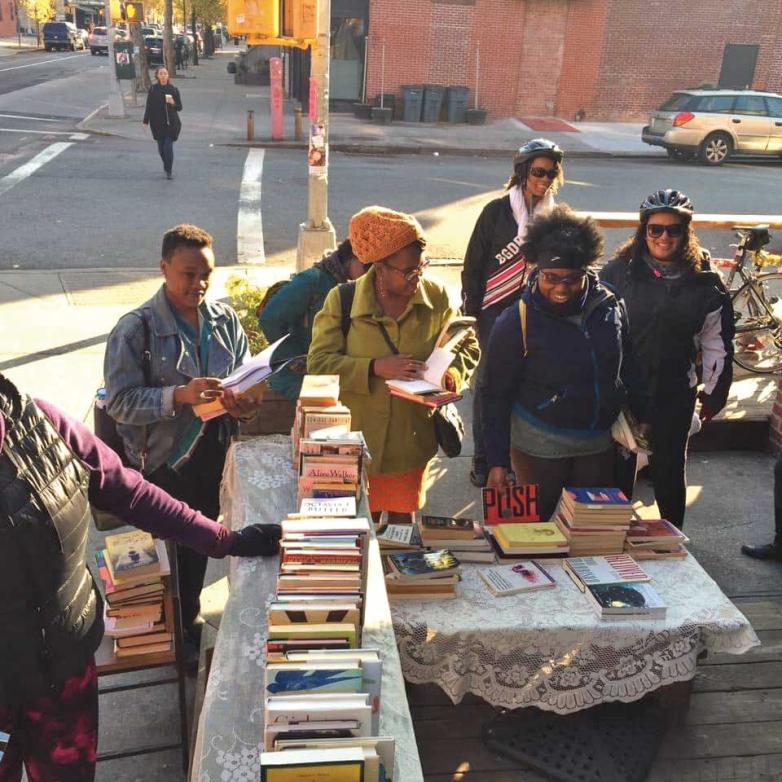

In 2022, she deepened her commitment to that vision by signing a five-year lease on a narrow Bed-Stuy storefront where the library now resides. A year on, floor-to-ceiling bookshelves line the walls, and a children’s section occupies the rear. There’s a free store for clothing, household goods, and other non-book items by the entrance and a backyard garden alive with flowers and herbs. The move to a brick-and-mortar space, which was supported by crowdfunding, was partially one of practicality: The library’s collection had grown to well over 5,000 books, meaning Akinmowo had to transport a selection in and out of storage for each pop-up. At the same time, she observed the joy the meetups brought her neighbors and began dreaming up a dedicated space where people could gather without having to buy anything—a growing need in the historically Black and rapidly gentrifying neighborhood.

“People wanted to have a space where they could just be with the books long term, with other people, and also chill,” Akinmowo says. “I felt it was really important to have a Black cultural community space in Bed-Stuy. Unfortunately, it seemed like whatever spaces could’ve been for us were disappearing and turned into wine shops and coffee shops.”