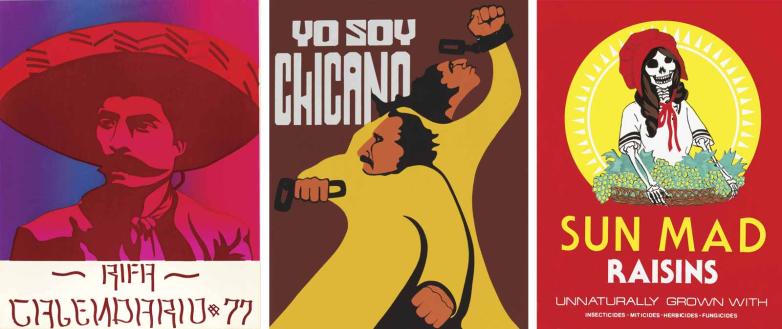

The 119 works on view, from linocuts to digital art, come from the museum’s holdings—an archive indebted to lifelong collectors and donors like Cárdenas, who today likely has the largest Latinx art collection in the United States. They make clear the lasting influence of Chicanx print networks advanced by players like the Los Angeles–based arts center Self Help Graphics; the serigraphy-focused nonprofit Serie Project in Austin, Texas; the San Antonio, Texas, artist collective Con Safo; and the United Farm Workers’ own print shop, El Taller Grafico. From these webs grew strong intergenerational mentorships between artists addressing enduring issues including labor abuses, police brutality, and immigrant rights. One can trace lineages between pioneering figures like Malaquias Montoya and Rupert García to younger artists such as Carlos F. Jackson, Juan Fuentes, Favianna Rodriguez, and Oree Originol.

Their works draw on diverse creative springs from Pop Art to Dada, from Cuban to Chinese graphic traditions. Rupert García’s striking posters call attention to rights for Latinx and Black communities, underscoring solidarity in struggles. A graffiti-influenced screenprint by Richard Duardo commemorates Aztlán—the mythic Aztec homeland that ties Chicanx empowerment to indigenous origins. Ester Hernandez’s 1982 screenprint, Sun Mad, replaces the smiling girl on Sun-Maid raisin boxes with a calavera (skeleton) to denounce grape farmers’ exposure to toxic pesticides; in 2008, she printed Sun Raid, adding, among other symbols, a wrist bracelet to critique widespread immigration raids.

The uncompromising forms and messages of Chicanx graphics have long fueled their dissemination, which has only become easier with the internet. Anyone can download a customizable template of Favianna Rodriguez’s pro-migration poster of a butterfly on the artist’s website. Or engage with augmented, reality-enhanced portraits by Xico González, who depicts myriad figures from a Palestinian girl to civil rights activist Yuri Kochiyama. His vivid images echo the magnetism and dignity of posters from El Movimiento that also honored everyday folks facing and fighting injustices, no matter their background.

The exhibition is filled with resonances between past and present, within the story of Chicanx graphics but also beyond it. “These works dovetail with a lot of debates about who we are as Americans, what our history is, and whose history is privileged,” Ramos said. “Our understanding of what is American is totally incomplete. When you include Latinx perspectives, it changes the whole picture.”