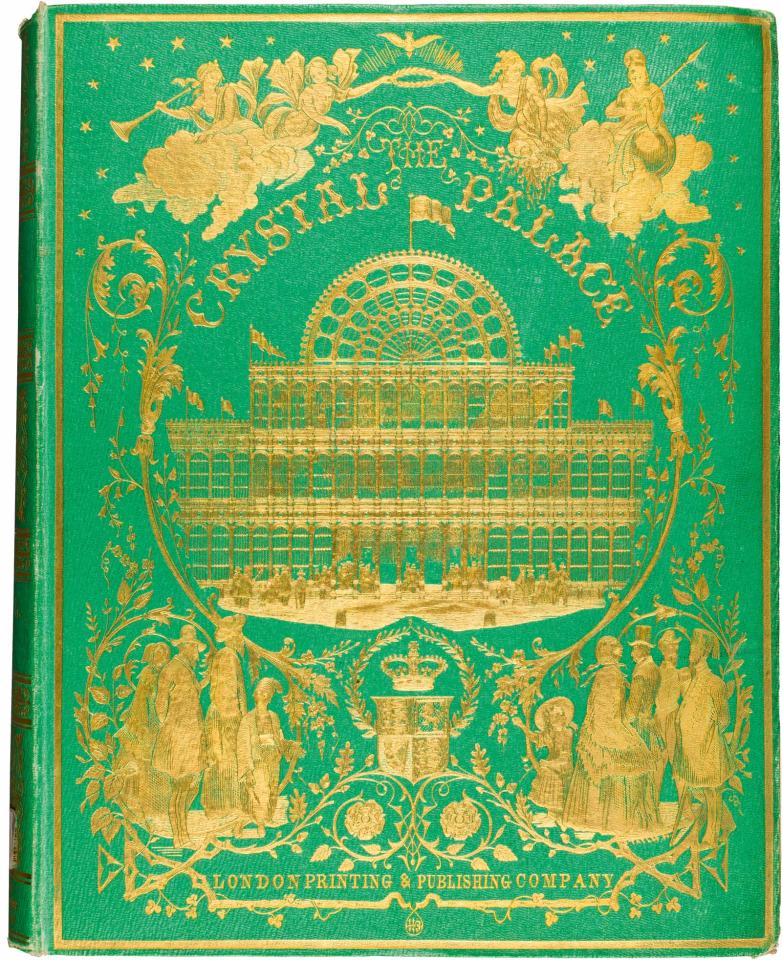

“I’m 100 percent sure that I’m not the first person to wonder if bright green book cloth was colored from emerald green,” Tedone said. “But I happened to be in the right place to have it tested.”

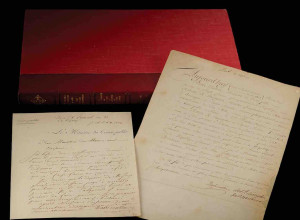

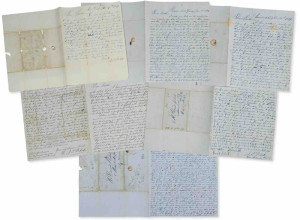

Thus began a journey for Tedone and Grayburn that has since been named the Poison Book Project. The duo has tested hundreds of books from the designated time period with the unique green color from their employer’s collection, as well as some books from other collections. They found nine “poisonous” books in Winterthur’s collection, and even made a trip to a local used bookstore and found one that tested positive for emerald green. They have since begun distributing color swatch bookmarks that can help people visually compare their “green” nineteenth-century books to the shades now known to be hazardous.

“We really have two goals with the project,” Tedone said. “One is to add to the body of knowledge about this period of bookbinding history—there is a gap in knowledge because nineteenth-century book cloth was a heavily guarded trade secret, so we don’t have a deep understanding of the way it was manufactured and which types of dyes and pigments were used.”

The second goal, Tedone explained, is to raise awareness of the potentially harmful compounds in Victorian book cloth, and to educate collectors on proper handling protocols. Some steps handlers can take if they suspect books in their collection may contain lethal chemicals: wear nitrile gloves when handling the books, wash hands after handling the books (even if gloves were used), and handle the books on hard surfaces, such as a wooden table, and wipe down surfaces afterward.

“Arsenic can be dangerous if it seeps through the skin of your hands, but it’s especially harmful if it’s ingested orally,” Grayburn said. “We approached the University of Delaware’s soil testing lab because we wanted to put a number on just how toxic this book cloth was. What they found was that if someone were to ingest the volume that was tested, it would kill them several times over. While no one is trying to eat these books, it does give an indication of how much toxicity we’re dealing with.”

The scientists intended to consider a number of other distinct book cloth colors from the same era that might be potentially unsafe, but the pandemic brought that research to a halt. For now, they’re focused on helping the public understand which emerald-hued books are poisonous, one bookmark at a time.