A Form Worthy of Its Contents: The Folio Society at 70

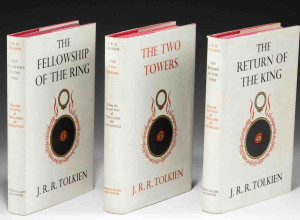

This year marks seventy years since The Folio Society began publishing beautiful editions of global literary classics. To mark the occasion, the publishing house is offering a showstopping selection of titles in its fall catalog--Virginia Woolf's A Room of One's Own, a two-volume set of The Little Prince, and other great books. In addition, London's Victoria and Albert Museum is hosting an exhibition entitled The Artful Book, featuring illustrated books, bindings, and original artwork from the Folio Society's vast archives. Highlights include commissions from illustrators like Quentin Blake, Sara Ogilvie, Kate Baylay, Neil Packer, and many others.

Folio Society's Editorial Director Tom Walker recently spoke about the milestone year, how they put together this recent catalog, and how he hopes Folio Society will continue to honor the company creed of producing books "in a form worthy of their contents."

BBR: This year marks the 70th anniversary of Folio Society. What influenced the selections in the fall catalog? How did you decide what made the cut? What was the theme, if any, for the fall titles?

TW: These are all significant works which had the potential to become exquisite reading editions. How the cut is finally made is a long process which starts life around two years prior to publication. The selection is a combination of constantly reading in new and classic areas; understanding what our readers want, and indeed asking them directly about our ideas; curating these ideas against our backlist and then discussing what a Folio edition might bring to the work, whether that be a new introduction, commissioned artwork, a new picture selection, or simply a perfect work of material production. The labour of a book, or a catalogue, can be quite hotly contested amongst us at Folio, but my ultimate guide is that we must be genuinely excited by the prospect - it is only then that we can engage with our customers reader-to-reader, as it were, and create something which is truly exciting for us both.

Subjective judgement also comes into it, I must admit: from The Little Prince to The Spy who Came in from the Cold, these are indeed some of my favorite books. The overarching criterion though is that we at Folio are excited by the process of transformation. We have, for example, published Great Expectations a number of times in our history, but this is almost the most thrilling book of the catalogue for me because we were able to make those tiny, multiple judgements in areas like typography or cloth pattern or paper choice - and we have been able to create a completely new, modern edition which is still deeply respectful of the heritage of the great work. We treat each book we work on with the same level of individual attention to detail, and this I think is Folio's most significant contribution over the years - its unique ability to add depth and texture to a reading experience.

BBR: The Little Prince two-volume set is magnificent, and follows on the heels of the Morgan's exhibition in 2014. Could you talk about the process of reintroducing this book to a new generation of readers? What makes this translation different from previous iterations? Also, the illustrations seem to pop more than in previous editions--could you talk a little about what went into that production process?

TW: It's a book I've wanted to publish since I started at Folio a decade ago. I was adamant that the only way we would publish a Folio edition was if we could create something absolutely worthy of the text. For Saint-Exupéry's illustrations I knew that we would be able to reproduce them to the very highest standards, but it took a lot of research at the British Library comparing various early editions, to find the best versions to work from. Our production team then spent days working on them to ensure the colour and integrity is of a quality not seen since its first publication in 1943.

Whilst researching the various editions, we wrote to the Morgan Library and Museum in New York for advice as to which versions to use, and it was then that I realised we had a whole new opportunity. As you mention, the Morgan inherited Saint-Exupéry's early sketches in watercolor, which he worked on in New York during the war, but which were never published in the final version of his text. I went to view these in New York last year, and the curator there who created the Saint-Exupéry exhibition on 2014 is very much a fellow fan of his work, and was so generous with her knowledge that it felt only right that she should pen the commentary volume. She also lent to me a mid-century French edition of the work, with a stunning binding by designer Paul Bonet, which we ended up replicating on one of the volumes. The final element I wanted to be sure of was the introduction, and frankly there could be no finer author for this than Stacy Schiff, who quite apart from being Saint-Exupéry's biographer, is a superb writer. The final version is, I hope, made by devotees for devotees - and it is one I personally am very proud of.

BBR: The LP commentary was written by Christine Nelson, who curated the 2014 LP exhibition, and she discusses preliminary and revised sketches and scenes for the book. What do you hope readers learn from this volume?

TW: There is much to be learnt on every page of this volume, but I think what has stayed with me most is the complexity of thought which Saint-Exupéry was obviously undertaking, in order to create a work which ended up so elementally simple. That seems to me almost the definition of greatness in the literary sphere, that the artist is able to bring this multitude into a series of resonant symbols which he has created - in this case, both in words and image.

BBR: What is it about this visitor from Asteroid B612 that remains relevant and captures our imagination?

TW: The Little Prince is one of the most elusive, untouchable characters in literature. His own history is only ever alluded to with such a lightness of touch that he feels as fragile a presence as the author himself. I suppose because of that we readers will always try to fill the vacuum, to take Marvel's line, and impose whatever meanings we need to upon him. It is particularly tempting now to think of the work as an allegory for innocence and experience, and for the voice of compassion and of the meek to be heard in a brutal and often nonsensical world. Whenever we do that though, I have the feeling that the Little Prince himself is resisting such an imposition.

This must in part be due to the beautiful marriage of text and illustrations, which I am of course particularly alive to. The final pages in particular, where Saint-Exupéry strips his artwork down to two lines to represent a vast expanse of desert, are hauntingly good and keep one's imagination completely engaged without imposing meaning. What storytelling!

BBR: What else would you like FB&C readers to know about the 70th anniversary of Folio Society? How else are you marking the occasion?

TW: We ran a huge poll last year to decide the two books - one fiction and one non-fiction -- which our longstanding readers would most like to see as Folio editions. These will be announced very soon. They are both magisterial works and we are delighted to be publishing them.

We are also very proud to have a display specifically on Folio's history at the world's leading museum of design, the V&A in London -- I urge you to go if you are able.

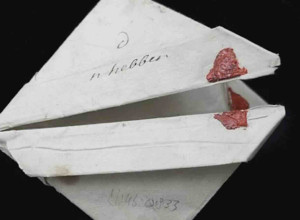

As part of the selection of materials for the display I spent a lot of time rummaging in our archives, and came across one particular document which I found a very fitting way to think about our anniversary year. It was in fact our founding document, the paper on which Charles Ede drafted the proposal for The Folio Society in 1946/7. He writes of Folio as being 'a sort of crusade...to provide books at a reasonable price whose content will be of lasting value, and whose format will be equal to the best production of modern private presses.' The fact that we believe in and uphold these values as much today as in 1947 is, I think, the finest possible way to celebrate our seventieth.