Gathering the Spirits: A Guide to Collecting the Occult

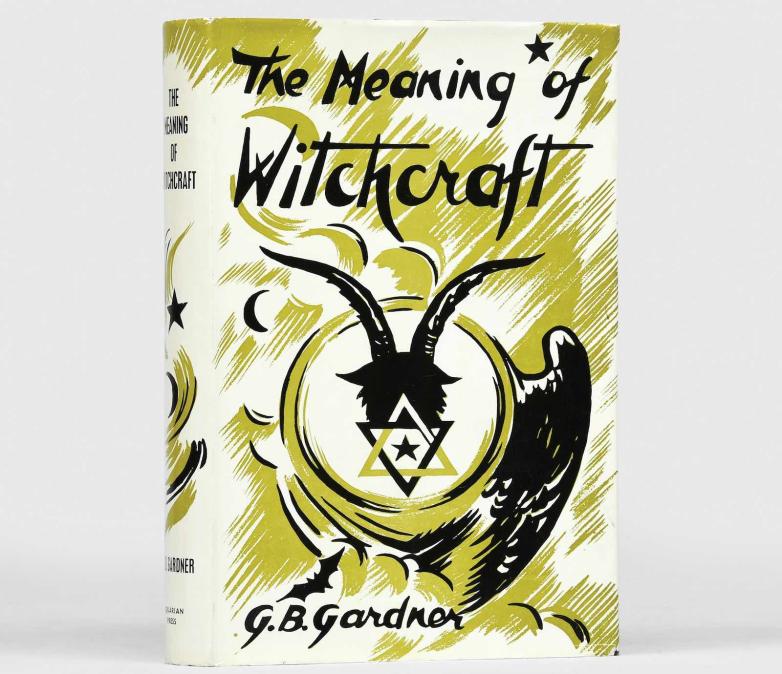

Gerald Gardner’s The Meaning of Witchcraft (1959)

Occult and esoteric works offer a broad church of material for collectors, writes Suzanna Beaupré from Peter Harrington. Its scope ranging from legal accounts of early modern witch trials through to 20th-century literature inspired by those on the other side, travelling through divination, alchemy, tarot, stage magic, conjuring, and many other weird and wonderful avenues.

Peter Harrington’s first catalogue to delve into the occult, Friends on the Other Side, Journeys in the Occult, attempts to showcase some of this rich treasure trove of collecting potential, and is a good place for us to start when looking for examples of the main sub-genres and “essential” pieces for an occult library, as well as some of the more niche topics you could carve your own space in. Landmark collections such as those of artist Robert Lenkiewicz, which sold at Sotheby’s in 2003, and magician Ricky Jay, part of which sold at Potter & Potter earlier in the year (part II comes up on 28 October) offer an indication of the wide range of possibilities available to an occult collector.

A traditional occult library will invariably aim to include key early works on witchcraft such as Reginald Scot’s radically sceptical 1584 work The discoverie of witchcraft (a copy with fascinating early annotations we have in the catalogue), Jean Bodin’s witch-hunting guide De la demonomanie des sorciers (1580), or Johann Weyer’s analysis of the phenomenon De praestigiis daemonum (1563).

Perhaps the most famous in this genre is the Malleus Maleficarum, commonly translated as The Hammer of the Witches. Although undoubtedly important in its own time, this work really found its fame following its highly sexualised translation into English by eccentric occult scholar Montague Summers in 1928. Copies of both early editions and Summers’s translation are highly collectable: a copy of the fourth overall edition of the Malleus, published in 1494, recently sold at auction for $43,750 (Christies, 23 Apr 2021), while copies of Summers’s edition can be picked up more in the range of a few hundred.

An increasingly popular area to collect is turn-of-the-century works by spiritualists and psychical researchers, whose highly visual publications offer an appealing glimpse into Victorian society. Spirit photography flourished in the late 1860s and early 1870s, with photos created by manipulating collodion wet plates, and examples of the medium are highly sought after. Many, including Arthur Conan Doyle in his collectable 1922 work The Case for Spirit Photography, maintained that while fraudsters were out there, true spirit photography was possible. As spiritualism was one of the fastest growing religions of the Victorian period there is a consequent wealth of published material to delve into.

In the 20th century we can see what is often described as the occult revival, with rising interest in paganism and wicca, as well as Satanism, astrology, and new interpretations of tarot. Introductions to these modern forms of magic by wiccans, such as Gerald Gardner’s Witchcraft Today (1954) and The Meaning of Witchcraft (1959), Stewart and Jane Farrar’s The Witches’ God (1989), and Vivianne Crowley’s Wicca: The Old Religion in the New Age (1989) can be a good place to start a collection. It would be remiss here not to mention two works often cited as foundational texts for modern magic: Charles G Leland’s 1899 work Aradia or the Gospel of the Witches, a study of witchcraft in Italy, and Margaret Murray’s canonical and contentious 1921 work The Witch-Cult in Western Europe.

Finally, if you want to branch out of the mainstream, the occult offers many routes. An area of collecting which has exploded in France is “magopinaciophilie” – that is collecting the highly ephemeral flyers that magical practitioners known as marabouts distribute to advertise their skills. We have a collection of 128 such flyers in the catalogue dating from the 1970s to 2020, but this is an area in which any lucky visitor to Paris may be able to start collecting, if they know where to look. You may also spot similar flyers in larger cities such as London, Liverpool, or New York. Although popular privately, interest in these printed flyers is just starting to be reflected institutionally and is a good example of how private collecting can be at the forefront of trends in institutional acquisitions and academic study.

This is a guest post by Suzanna Beaupré, a cataloguer and bookseller at Peter Harrington. Having completed an MPhil in Early Modern History in which she focussed on the history of women in the book trade and the visual culture of heresy and witchcraft, she has continued these interests in her role at the London-based rare book firm. The books she works with reflect these topics, as well as food and drink history, the study of folklore, and private press works.