Magnificent Obsessions occupies the Smithsonian Libraries’ main gallery, a dim, low-ceilinged space on the ground floor of the American History Museum, not far from the flashy Batmobile that greets visitors in the nearby lobby. The smallness of the gallery belies the vastness of the collection, which numbers about two million volumes spread among twenty-one specialized research library branches in the sprawling Smithsonian system. That means the exhibit has a lot to draw from: some 40,000 rare books and 10,000 manuscripts, from natural history to cookbooks, design books, 400,000 pieces of trade literature, souvenir materials from World’s Fairs, pop-up books, and other printed material that somebody somewhere had the good sense to save.

By including not just objects but the stories and photos of the people who collected them, Magnificent Obsessions conveys a sense of breadth and depth in spite of the constricted space. The seventeenth-century Dutch pharmacist Albertus Seba serves as a sort of guiding spirit for the exhibit. An avid collector of plant and animal specimens, Seba commissioned hand-colored engravings that showcased, in book form, his “Cabinet of Natural Curiosities.” In the exhibit, the volume is opened to a spread of cephalopods in hues of blue and red. Lovely to look at, Seba’s Locupletissimi rerum naturalium thesauri also created a model of how to organize and classify collections, according to Thomas.

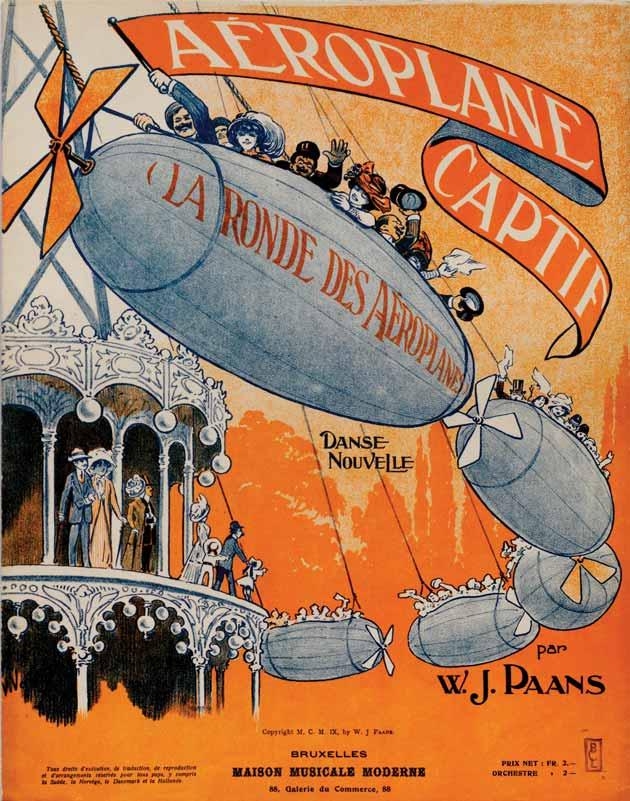

If you want to build a serious collection, it helps to have means. Sarah and Eleanor Hewitt, the granddaughters of industrialist Peter Cooper, used their fortune to pursue their love of decorative arts and design. They snapped up books of patterns and furnishings that escaped the notice of more “serious” male collectors. “These are chair designs and cabinetry, lace patterns,” said Thomas. “Now New York designers go nuts over this.” Magnificent Obsessions includes a Hewitt-owned book of Thomas Chippendale designs that are marvels of detail. The heiresses’ once-niche interests produced a national cultural asset: In 1897, the sisters founded what became the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum in New York City.

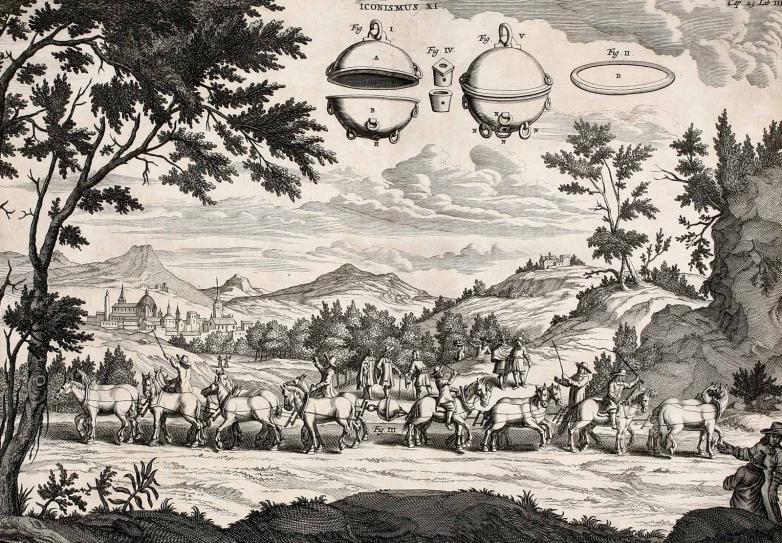

Bern Dibner, a Ukrainian-born electrical engineer who emigrated to the United States in 1904, did not inherit a fortune, but he made one during the electrification boom of the 1920s. He was fascinated by the work of Leonardo da Vinci, but “he wasn’t going to be able to collect Leonardo,” said Thomas. He could, however, afford to buy other seminal documents related to the history of science, many of which were still available for purchase. Over the years, Dibner acquired a world-class collection, including works by Galileo, Copernicus, and Newton, now part of the Dibner Library of the History of Science and Technology, one of the Smithsonian Libraries’ major collections.