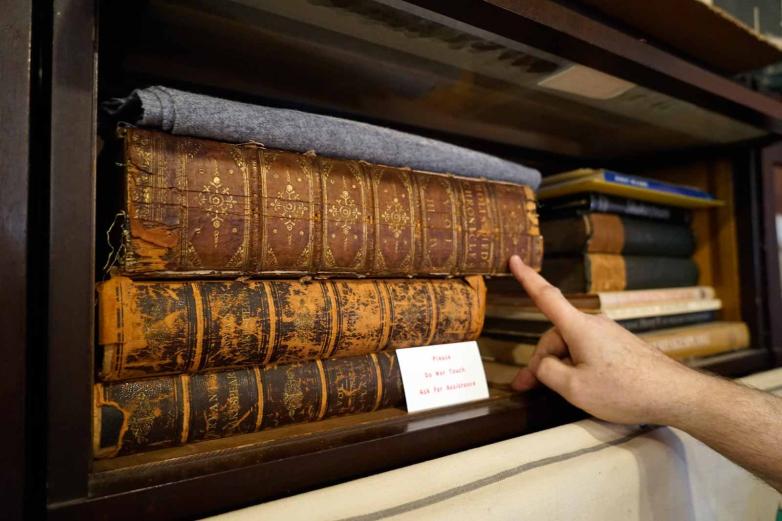

When Thad Taylor died in 2006, the nonprofit was forced to relocate to smaller quarters but tried to stay true to his original goals. “The mission of the Shakespeare Society of America has always been about bringing the brilliance of the material out to the public, so they can actually see what was in original books, the original material from back then, and how important Shakespeare has been in that whole process,” said Terry Taylor, Thad’s nephew and current president of the SSA. “We have over a thousand books from earlier than 1900, and four hundred earlier than 1800. For various reasons, no one has seen every item in the collection. It’s beyond control on one level, but we’re preserving it for the future.”

One could understand the difficulties trying to control vast resources in a small space, especially when the resources keep expanding. A recent donation from the estate of a high school English teacher from Pennsylvania filled a tabletop during a recent visit. Shakespeare-themed plates, books, buttons, keychains, and a hoard of pewter finger puppets from the plays—in all, thirty boxes of items, many still in those boxes.

Taylor displayed a set of Shakespeare’s complete works from 1805 that was owned by the first John Barrymore, given to the SSA by John Barrymore II when his son, John Barrymore III, was playing Hamlet in nearby Carmel-by-the-Sea. Close at hand is a three-volume set of The National Shakespeare, a faithful reproduction of the first folio of 1623, produced with the Royal Society of Art in 1888–1889.

But it’s the giant Collection of Prints, from pictures painted for the purpose of Illustrating the Dramatic Works of Shakespeare published by John Boydell in 1803, that really catches the eye. Boydell, an engraver himself, engaged a host of other master artists and engravers to paint lavishly detailed scenes from the plays, which he displayed in a gallery. He had the engravers cast the scenes on copper plates, and then used a reverse printing process to emblazon the scenes on folio-sized paper. The ninety images are magnificent—a moonlight-on-water scene from The Merchant of Venice is mesmerizing, and Caliban has never been more vividly fiendish than in Boydell’s print illustrating The Tempest.