Renaissance RE-Invention

At the Newberry Library, an unprecedented exhibition studying the Nova Reperta, a sixteenth-century print series that celebrated the technology of the times, gets underway

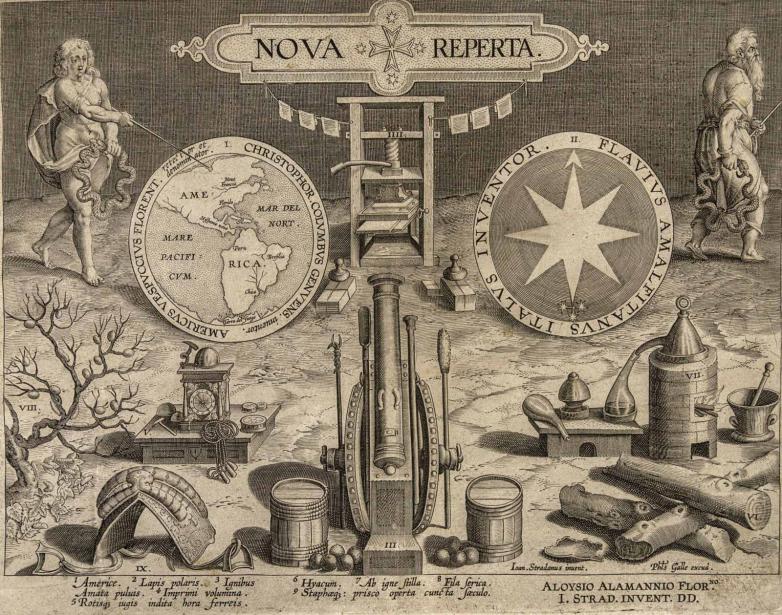

Our society’s fascination with cellphones and other distracting novelties was not born in the current Internet Age, but started with astrolabes and other scientific instruments in the Renaissance. These early technologies inspired the artists and writers who founded the humanities in the first place. What inventions did they think were vital for them to survive and for the arts to flourish? To answer that, we look to a print series dedicated to the most cutting-edge of these ‘new discoveries.’ Called the Nova Reperta, it forms the nucleus of “Renaissance Invention.” These twenty engravings celebrate recent advances, from the ‘discovery’ of the Americas (the left roundel map), to the frightening advances of gunpowder-powered war machines (the raised cannon at dead center), to the fashionable development of European silk production (the silkworms on a mulberry tree at far left). They also home in on different modes of printmaking. By including both a book press (at the top of the title page) and an intaglio roller press (the final plate), the series refers back to the prints themselves—and makes the medium the message and harbinger of the Renaissance’s viral communication explosion through print.

I am co-curating Renaissance Invention: Stradanus’s Nova Reperta, with Lia Markey, our director of the Center for Renaissance Studies at the Newberry. Lia and I both have art museum exhibition experience, and she is an expert on the artist who designed the series, Johannes Stradanus (1523–1605), aka Giovanni Stradano (in Italy) or Jan van der Straat (in the Netherlands). Stradanus was active in Florence but worked with printmakers in Antwerp working with the Plantin Press to have his plates engraved and printed. Among the many series he designed, the Nova Reperta stands out as the most modern, and yet still remains the least researched. Produced around 1588, it identifies the nineteen most important inventions or discoveries of their current era or since antiquity. To bring the prints to life, we will display them together with more than forty Newberry items and loans of arms and armor from the Art Institute of Chicago, scientific instruments from the Adler Planetarium, and engravings from private area collections.

Stradanus generally presented his varied medicines and machines as positive developments, although then as now, the unknown brought unrest. Discussions about the long range of progress since antiquity was common at the time, with several publications of similar names appearing, such as Polydore Vergil’s De rerum inventoribus (1499) Guido Panciroli’s Nova reperta, sive rerum memorabilium recens inventarum (1602), and others assembling texts of recent advances as well. In contrast to these rather unadorned lists of things, Stradanus’s illustrations themselves become an innovation. But were nineteen (or more) innovations necessary? Statesman and philosopher Sir Francis Bacon summed up human progress slightly later on as including only the three most important innovations of all time. Indeed, these appear within the first ten Nova Reperta plates, as well as in the center of the title page:

“Printing, Gunpowder, and the Magnet … These three have changed the whole face and state of things throughout the world; whence have followed innumerable changes, insomuch that no empire, no sect, no star seems to have exerted greater power and influence in human affairs than these mechanical discoveries.”

Other scholars who helped choose Stradanus’s top Renaissance inventions were the friends of his Florentine patron, Luigi Alamanni. Alamanni was part of the mysterious Academy of the Alterati (Altered Ones), and its members might have become involved in the subject matter and project financing, quite possibly during the Academy’s frequent sessions. Given the possibility that the group found inspiration in libations, modern viewers might find it fitting that distillation appeared in the Nova Reperta. Yet they might equally scratch their heads at the inclusion of the apparatus on the title page next to a pile of guaiacum, a wood newly found in the Americas, then considered a panacea (for syphilis, gout, and other common ailments).

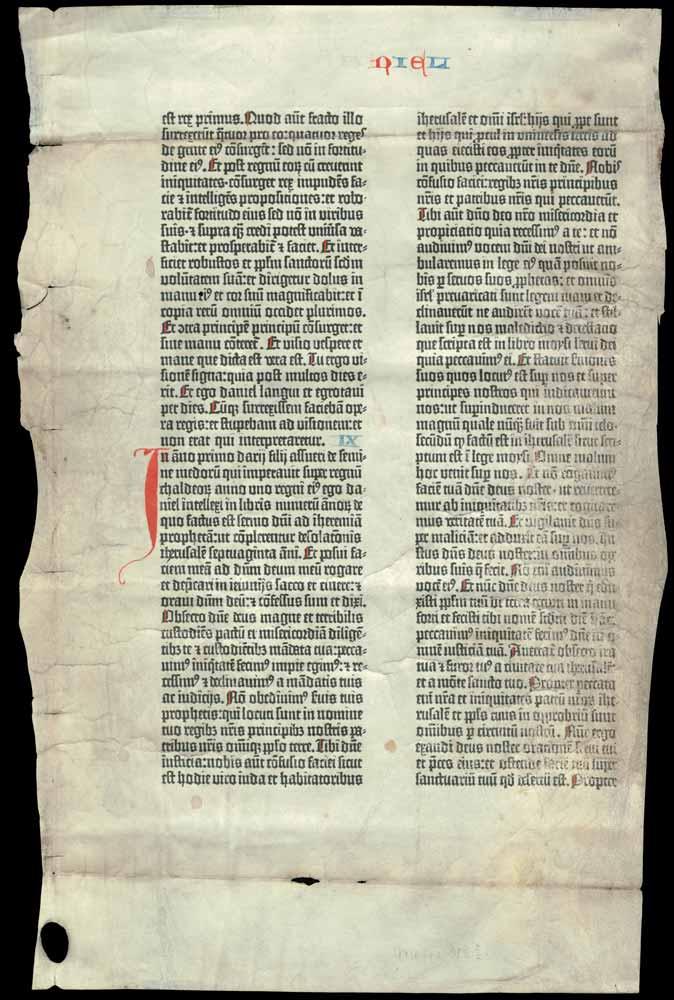

The Nova Reperta’s implication that these are exclusively Western Renaissance inventions is to be taken with a grain of salt. Of the first ten plates, Bacon’s favorite advances (as well as the nearby stirrup and silk) were in fact originally developed in Asia. To be fair, the Nova Reperta does not definitively identify Johannes Gutenberg as the inventor of printing, but he was named as a contender in correspondence between the artist and his patron. Although developed hundreds of years later than Eastern printing, the book press Gutenberg adapted from a wine press, and his molding of movable type, would be instrumental to its spread in the West. A vellum leaf from his 42-line Bible will be on display in Renaissance Invention, demonstrating both the elegance and efficiency of this new technology. It allowed Gutenberg and his workshop to produce 180 copies in only two years, about a third of the time it would have taken a scribe to produce a single one by hand.

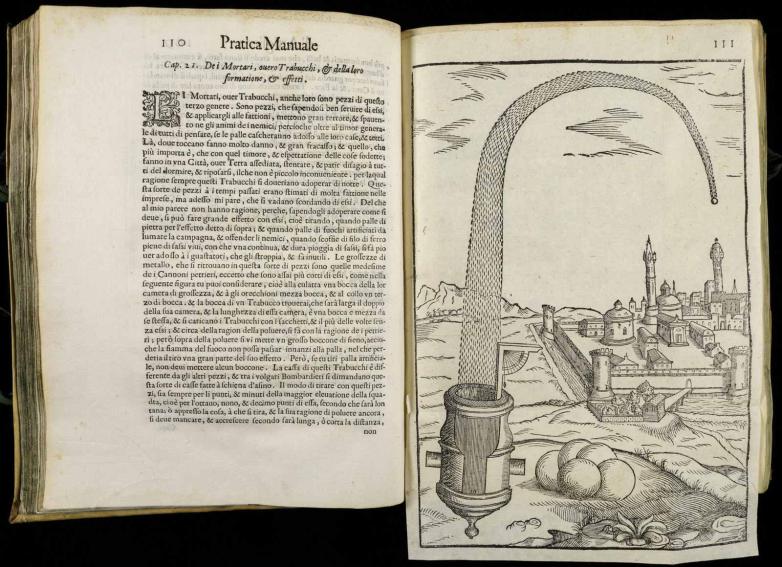

Bacon’s second invention, gunpowder, was Chinese in origin. Subsequently, not only Stradanus’s prints, but countless military manuals were produced to demonstrate siege weapons in use. Another early Newberry book, Spaniard Luis Collado’s practical artillery manual, pits a short-barreled mortar against an Eastern, possibly Ottoman, city. His dramatic woodcut is designed to help new recruits chart the hyperbolic trajectory of the cannonball. While a full-sized cannon could not squeeze into our exhibition galleries, we are borrowing a scale model from the Art Institute of Chicago from the same period as the prints. It is constructed from the same materials as the real thing: bronze for the barrel, and oak-strapped iron for the wheeled carriage that would help guide the full-fledged version into place for the next civic assault. With gunpowder came the ongoing risk of explosion, not only of the target if properly primed, aimed, and fired, but also of the barrel itself, should the parts have not been properly forged or transported.

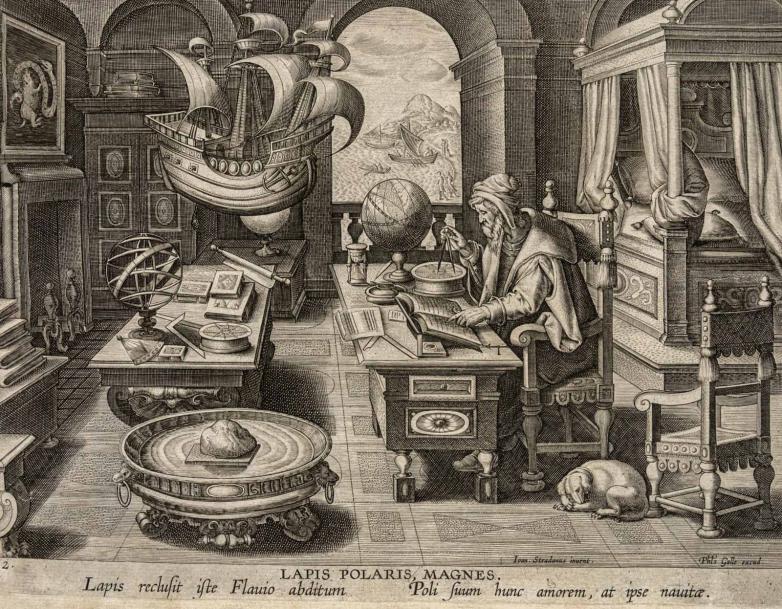

Bacon’s third and final choice of invention is the magnet, yet again a development that can be traced to China. His synecdoche alludes to the way this magnetized iron sample would have been used within a handheld compass and other devices for navigation in this time of aggressive international exploration. Seen on the Nova Reperta title page, the enlarged compass face becomes the circle to the center right showing the cardinal directions. With the map of the Americas, it flanks the printing press. In the “Compass” plate itself, the solitary scholar uses a compass at his desk, but a more impressive function of the magnet appears at the bottom left. Here is a much larger magnetized piece of the same metal, a lodestone, which with its increased polarity served for numerous experiments, and was a source of endless fascination for the nobility throughout Europe. Letters survive to prove that they constantly asked scholars to explain how magnets and their invisible powers worked. They were so prestigious that Galileo even gave a lodestone to a Medici family member. An Adler Planetarium lodestone will be on view at the Newberry, and will cast further light on the many obsessions documented within Stradanus’s futuristic and fascinating Nova Reperta. Perhaps the prints themselves served a similar purpose as gifts bearing knowledge of the past, present, and future.

Like a Renaissance engraving, book printing, lens-grinding, or clock-making workshop where every artisan has their place, this exhibition has already been the work of many hands. Even though it has not yet been installed, Renaissance Invention has already received a commendation from the 2019 Sotheby’s Prize, geared to celebrate curatorial excellence and champion the work of innovative institutions who strive to break new ground by exploring overlooked or under-represented areas of art history.

Renaissance Invention: Stradanus’s Nova Reperta will be on view at the Newberry from August 28 - November 25, 2020. An exhibition catalogue of the same title is available from Northwestern University Press, based on an international symposium held at the Newberry in May 2019.