For fifteen years, McIlwaine has had the dream job for a Tolkien fan: Tolkien Archivist, charged with sorting through an archive of papers, manuscripts, artwork, letters, objects, and assorted ephemera related to the Oxford don and creator of arguably the most beloved fantasy series of all time. For the last five of those years, she has been preparing for the Bodleian’s monumental survey of his work, Tolkien: Maker of Middle-earth, the first exhibition dedicated specifically to Tolkien in twenty-six years at the library, and the first time since Tolkien sold The Lord of the Rings manuscripts to Marquette University in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, that they have returned to England.

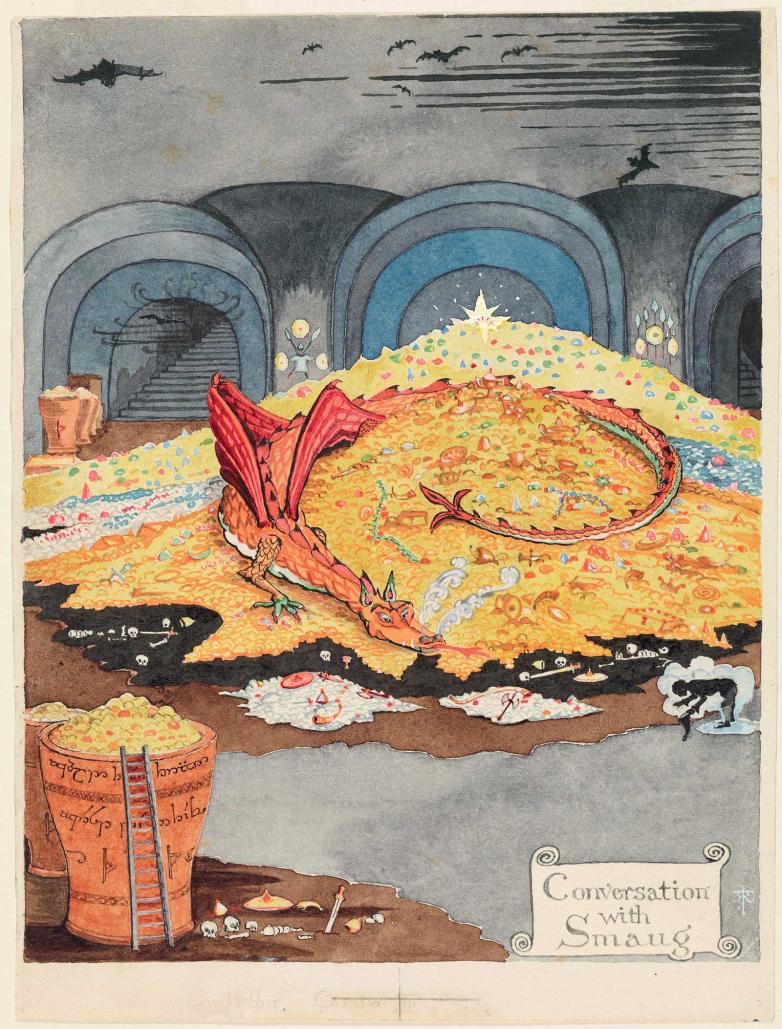

“Curating the exhibition has been a huge privilege,” said McIlwaine. “The most exciting part has been bringing all this unique material to public view for the first time in a quarter of a century. From the comments left in the visitors’ book in the exhibition room, it’s clear that people are genuinely thrilled (and frequently moved) to see Tolkien’s original drawings, paintings, manuscripts, and personal objects.”

While readying the exhibition, McIlwaine found correspondence from the not-yet-famous fantasy writer Terry Pratchett, and from novelist Iris Murdoch, who writes, “Dear Professor Tolkien, I have been meaning for a long time to write to you to say how I have been utterly delighted, carried away, absorbed by The Lord of the Rings.” (Murdoch also notes before her signature that she wishes she could say so in Elven tongue.)

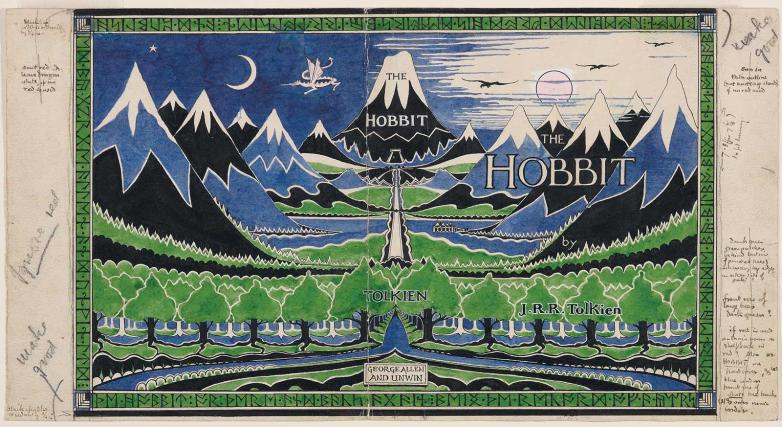

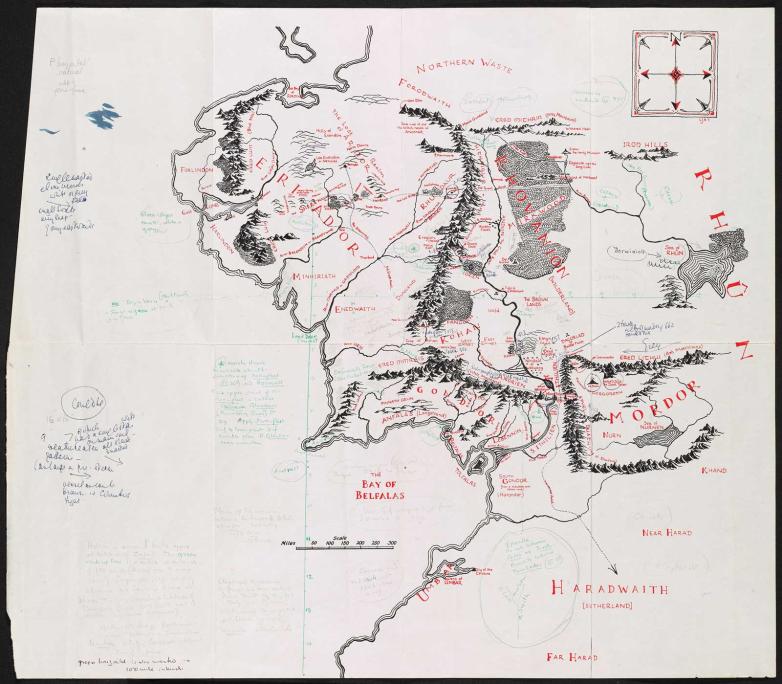

For such a significant exhibition, it is not particularly large. It doesn’t, for instance, foray into the film adaptations; instead, McIlwaine has homed in on highlights from the library’s archive in order to convey and document Tolkien’s life experiences that might have led up to his creation of the world that is Middle-Earth, which includes The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings trilogy, The Silmarillion, and other books, notes, and unfinished manuscripts that support his universe. Tolkien, there is no doubt, excelled at building entire worlds—mapping them out, populating them, and inventing new languages for its residents.

The exhibition is incredibly and unexpectedly moving. After Tolkien’s father died, his mother had no financial support and they had to rely on family, and then his mother died, too. He was a scholarship student at college, and he was a soldier. He certainly encountered hardship and trauma in life, but he didn’t seem to let it affect him. Instead, or perhaps because of all these obstacles, he relied on his education and allowed his love of language to become a secret, at first, obsession. If any of the setbacks of his young life scathed him, there’s little evidence—or there is plenty of evidence in the lack of evidence. He buried himself in research and writing, and it gave him the tools to escape, and then he made it accessible enough for a world of readers to join him.