Lot 3308 in the addenda to the sale catalogue, easily missed alongside the superb and scarce early printed books on offer, was for a copy of the Zeitlinger and Sotheran Bibliotheca Chemico-mathematica, along with “bound volumes of booksellers’ catalogues, mostly scientific.” This set of catalogues had been organized and bound in red cloth with maroon morocco gold-stamped labels to match the distinctive boxes half bound in red calf and red cloth with spines with gold-tooled titles that housed much of the rest of his collection. Meant to sit harmoniously on the shelf alongside the books they advertised, these volumes were a valuable reference source for Honeyman as he assembled and maintained his collection. We acquired the surviving 37 volumes of catalogues from this lot from Asher Rare Books & Antiquariaat Forum earlier this year, who in turn acquired the volumes from Joop van Gelder, a Dutch pharmacist and book collector, who acquired the volumes in the Honeyman sale. Taken altogether, the collection contains 179 individual catalogues from 40 bookselling firms, issued between 1910 and 1961.

Honeyman began sending his catalogues to be bound in the early 1930s, soon after he shifted his collecting priorities from literature to science. The first bound set seems to have been either volume five, containing part of the Sotheran’s Newton sale, or volume 34, a miscellaneous collection of four catalogues from 1930 and 31. As the space between these volumes suggests, his internal numbering system was a slightly later invention, created as he accumulated more catalogues. An added note on the front free endpaper of volume 34, which discusses a planned break in the numerical series to accommodate future Sotheran’s volumes, shows a little of his organizational thinking.

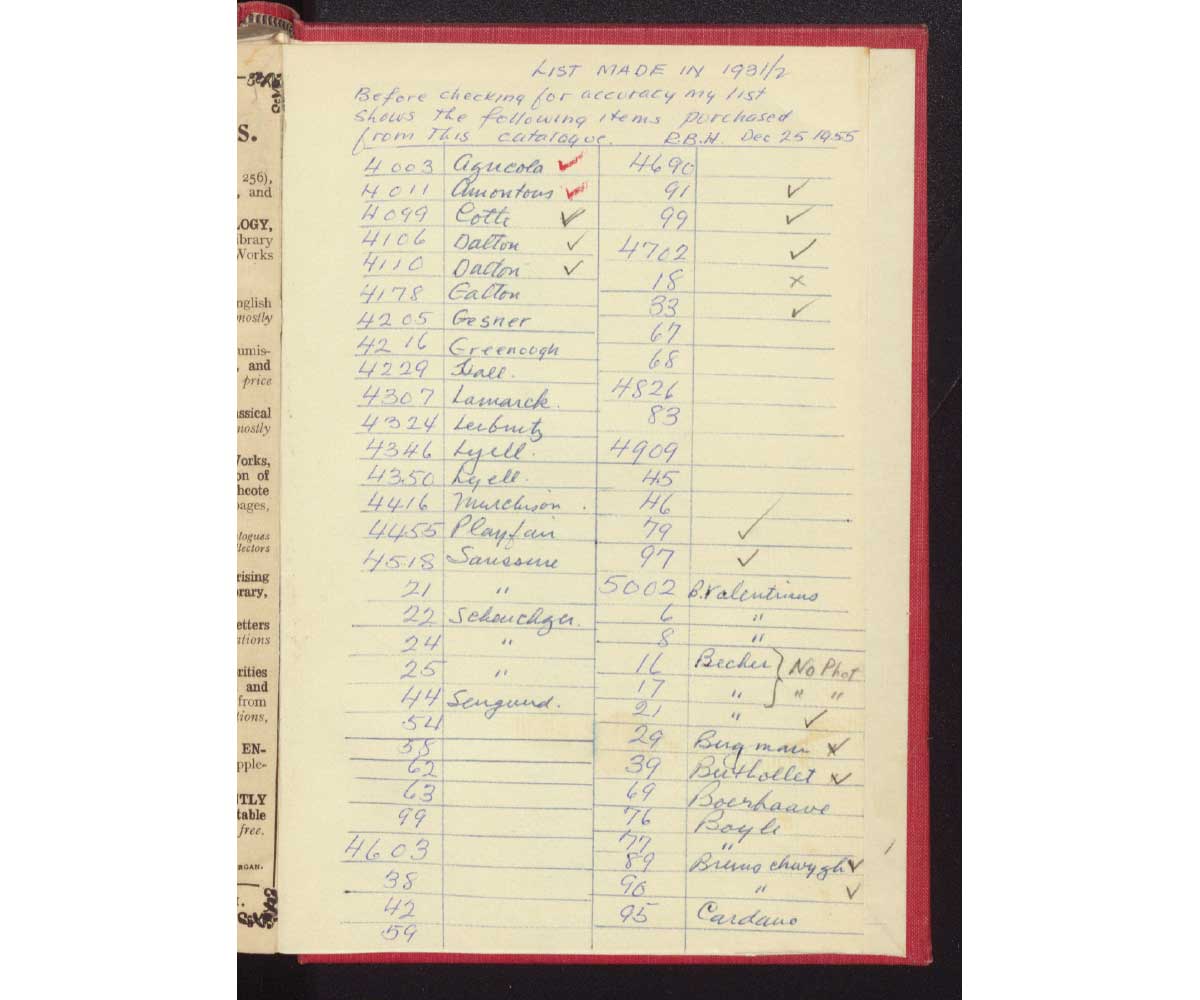

These red cloth volumes, which he referred to internally as “Red #,” were both a record of purchases and a reference source in their own right. In addition to the typical, spare markup seen in other collectors’ catalogues—checkmarks next to desiderata and hasty lists of purchase numbers scrawled on title pages and pastedowns—Honeyman left evidence of repeated use. Some individual catalogues bear dates, typically from the mid 1950s, indicating when he last “checked” the listings, and some, like his copy of E. P. Goldschmidt & co.’s list no. 17, bear the pencil note “Keep for reference.”

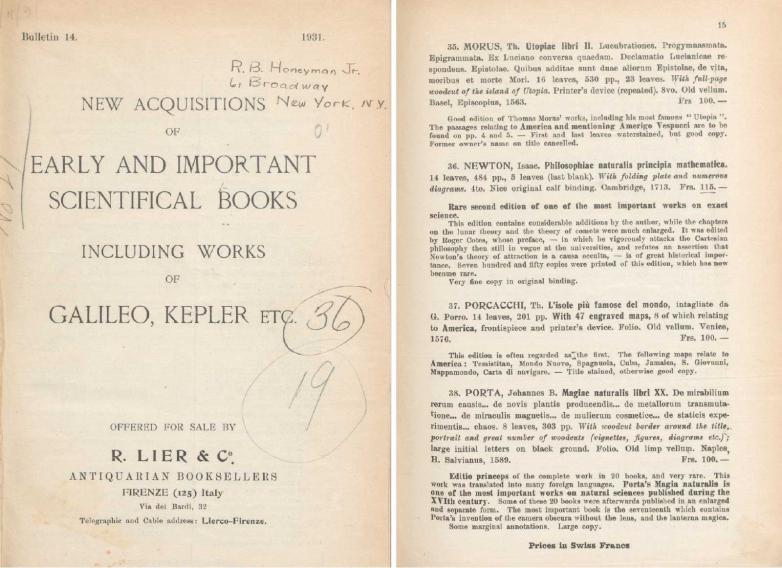

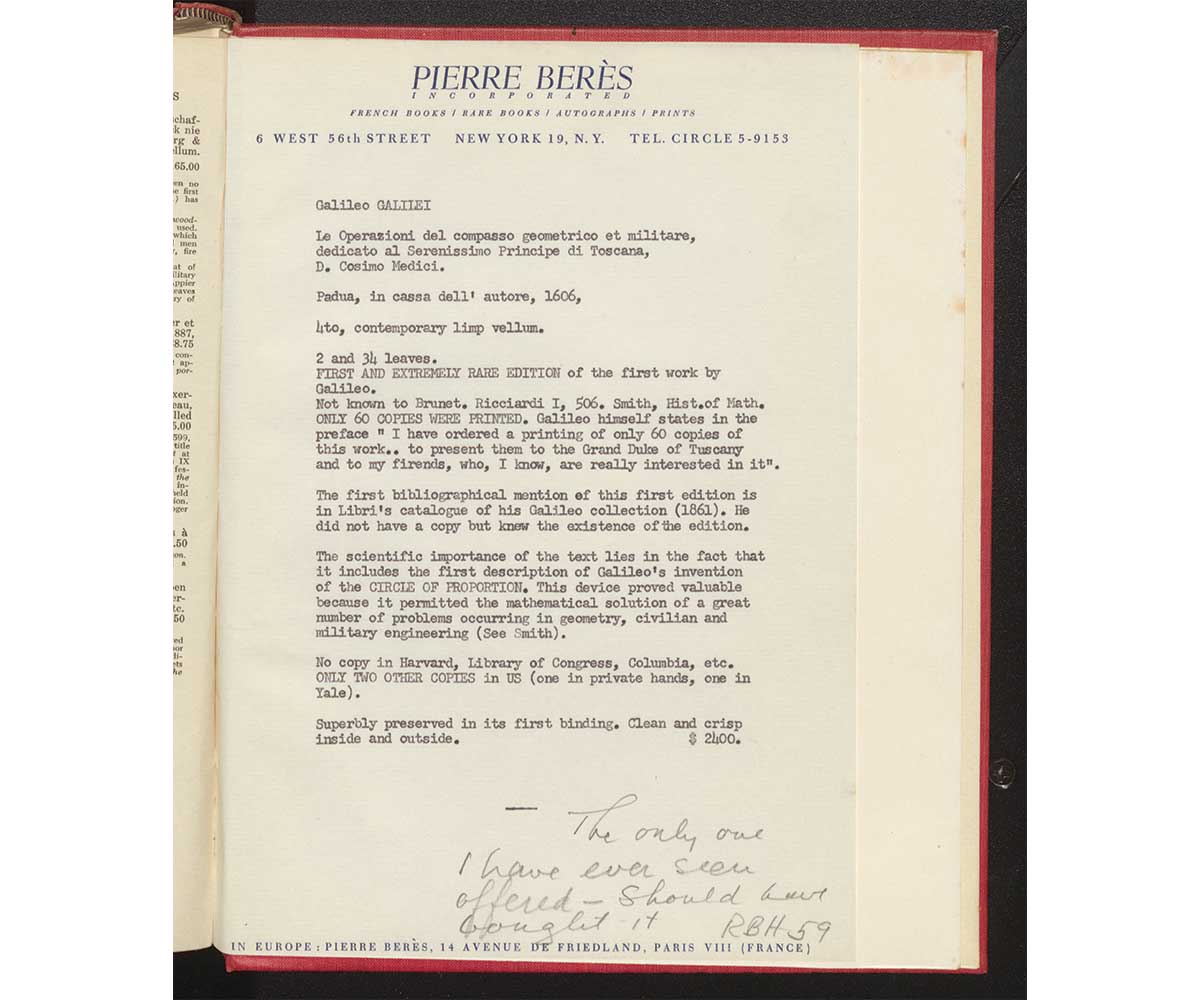

In other volumes, Honeyman offers more extensive thoughts, both about the accuracy of a seller’s descriptions and about how his own copies compare to those on offer. He paid special attention to his collection of the works of Galileo Galilei, offering extensive annotations on his copy of the 1931 R. Lier catalogue of Galileo works. In a later volume, he tipped in a bookseller’s advertisement from the Pierre Berès firm describing a copy from the 1606 first edition of Galileo’s Operazioni del compasso. He offers a simple lament in pencil, dated 1959: “The only one I have ever seen offered—should have bought it.”

Acquiring these catalogues was of great interest to us not only for these animating details of how Honeyman thought about and built his collection, but also for the wealth of provenance information they offer about our own holdings. Our library was a very active participant at the sale through our agent, Jake Zeitlin, purchasing 65 items in total. Included in these purchases were Kepler’s Mysterium Cosmographicum (1508) with the Platonic solids plate, and a copy of John Bevis’ Atlas Celeste (1750-1786).

The added information these catalogues provide gives us access to a ‘second generation’ of provenance information, which is useful for research and for security purposes. Added associations and ownership information tells us about the many uses to which a book has been put in its lifetime, and provenance of a particular copy is key in determining whether that copy is a fake or forgery. Outside of marks left on the books themselves, libraries and collectors typically have access to only one generation of provenance, or perhaps two: the immediate source of acquisition of the object, and the previous owner. Of course, ownership inscriptions and property stamps can provide further evidence, but not all prior owners decided to literally leave their mark on books in their libraries.

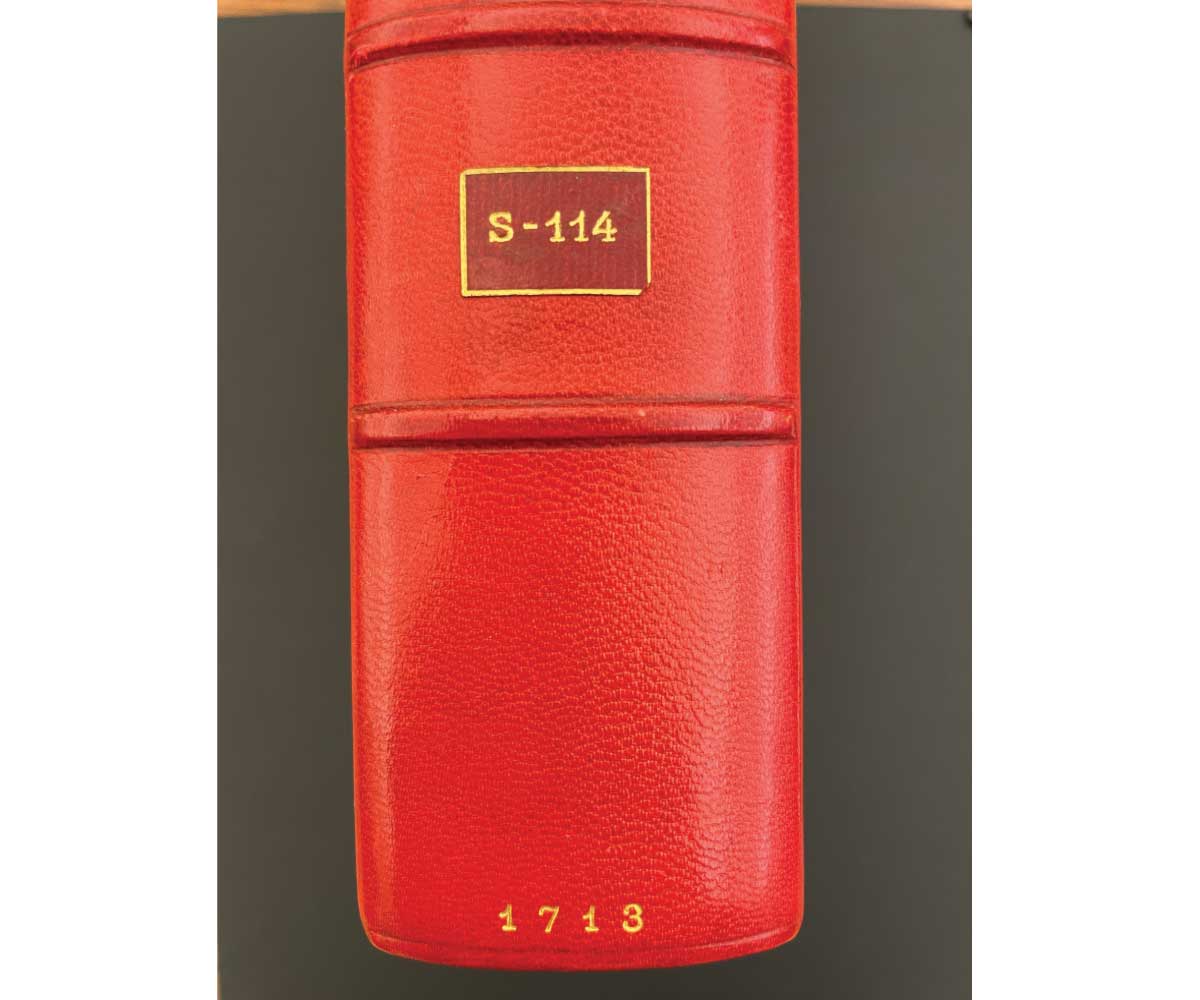

For Honeyman books, a few clues for dating his acquisitions are given in the introduction to the first volume of the sale catalogues prepared by Sotheby’s: the handwritten shelf marks on the front pastedowns or labels on his distinctive red boxes. The prefix “S” indicates a pre-war acquisition, and then books were numbered by order of accession. After the war, and likely with Honeyman’s expanding acquisitions, the books were re-numbered in a sequence beginning with the first letter of the author’s surname. And finally, about 1960, a second series of each letter was initiated with the addition of a lower case “a.” One other way to identify early Honeyman acquisitions is to look for his red leather bookplate, which Sotheby’s identifies as earlier than the paper bookplates.

We joined this known generation of provenance with the newly acquired catalogues to look deeper into the library’s copy of the 1713 edition of Newton’s Philosophiæ naturalis principia mathematica, lot no. 2303 in the Honeyman sale. This copy of Principia is housed in Honeyman’s distinctive chemise slipcase and box, with his early shelf mark (S-114) on an additional red label. The earlier leather gold-tooled bookplate appears on the front pastedown, along with a small black ink inscription in Honeyman’s hand:

No S-114

RBH

10/1931

18 Ens.

This inscription is not typical of the ex-Honeyman volumes at the library, but it does provide some helpful clues users might use to determine the source of this copy. The date of acquisition brought us to the 1931 catalogues in his collection, of which several included copies of the 1713 Principia. However, Honeyman made note of only one—no. 36 from R. Lier & Co’s Bulletin 14, a “very fine copy in original binding,” matching the description of the copy in our vault.

While the Honeyman catalogues have obvious benefits for our own holdings, our real goal in acquiring the collection has been to make it an accessible resource for other institutions and researchers. To that end, the Linda Hall Library’s digitization unit has scanned them in full, though the majority of the catalogues in the Honeyman Bound Bookseller Catalog Collection are still under copyright. These are accessible both on-site at the library, and through the library’s pilot program in Controlled Digital Lending (CDL). We hope that, by publicizing this acquisition, other holding institutions will take advantage of this resource and share in our project to study and promote the intersection of the history of the book and the history of science.