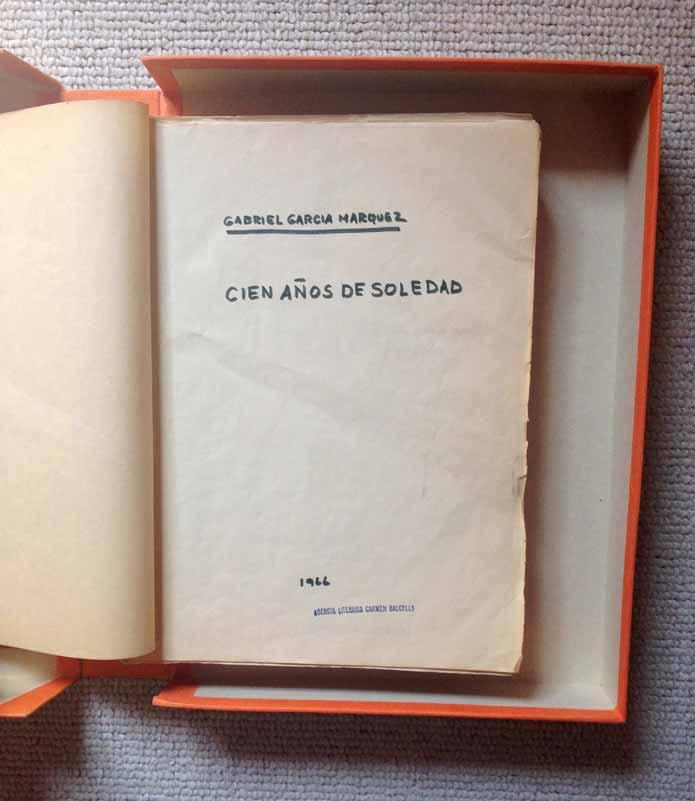

Most precious to Santana-Acuña, however, are two copies of the final typescript of One Hundred Years of Solitude. “I remember feeling out of a breath when I first touched it,” he recalled. Visitors to the exhibition, which remains temporarily closed but will reopen later this summer, will be able to see one of the typescripts while listening to a recording of García Márquez reading the first chapter of the novel, an experience that Santana-Acuña said gave him “goosebumps.”

The exhibit spans García Márquez’s whole life. In the first gallery, the author’s natal chart is on display; the next one boasts a first edition of Leaf Storm, the author’s first book, published in 1955, flanked by a William Faulkner typescript and a James Joyce galley (García Márquez cited both authors as major influences).

One of Santana-Acuña’s favorite items is housed in the seventh gallery: “a beautiful letter written by a nine-year old Ukrainian girl, who calls him a ‘genius’ and at the bottom of the letter drew flowers for him.”

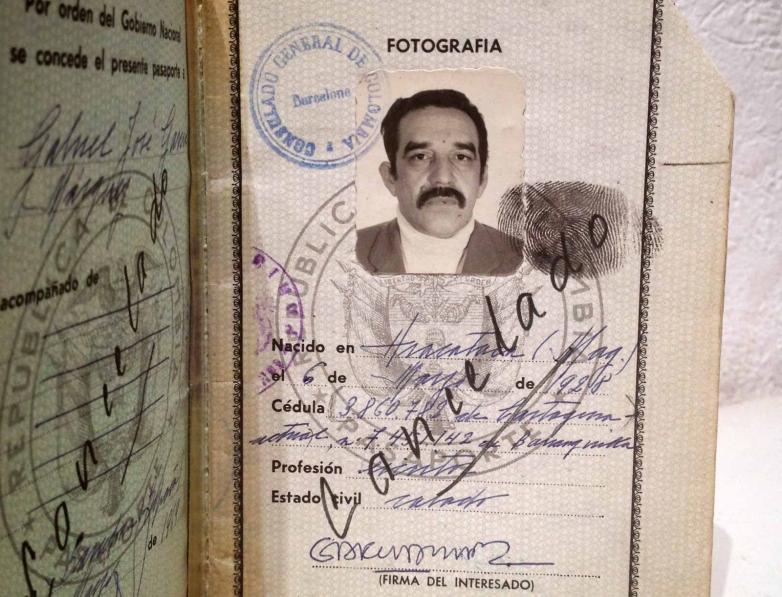

Santana-Acuña recommended that visitors to the virtual version of the exhibit take a look at García Márquez’s photographs. “There are plenty, and some of them give us an intimate understanding of the writer at work in his studio as well as about the man, the father, and the friend,” he said.

He also urged visitors to examine García Márquez’s scrapbooks. “García Márquez accumulated over his career twenty-one scrapbooks full of newspaper and magazine clippings from publications all over the world,” he said. “It is a really good way of seeing how his writing reached millions globally.”