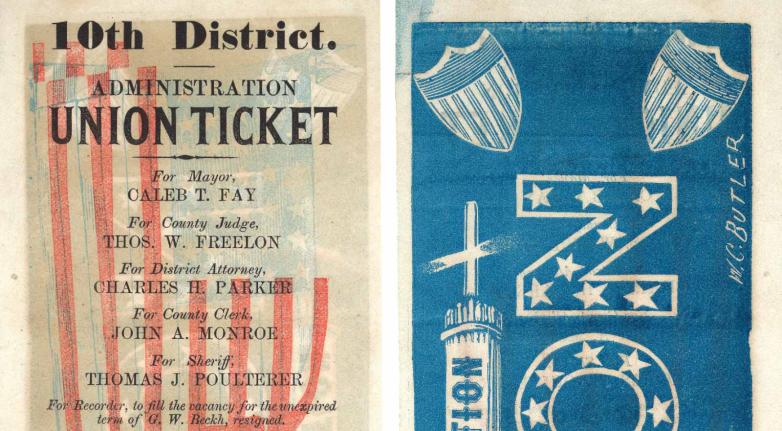

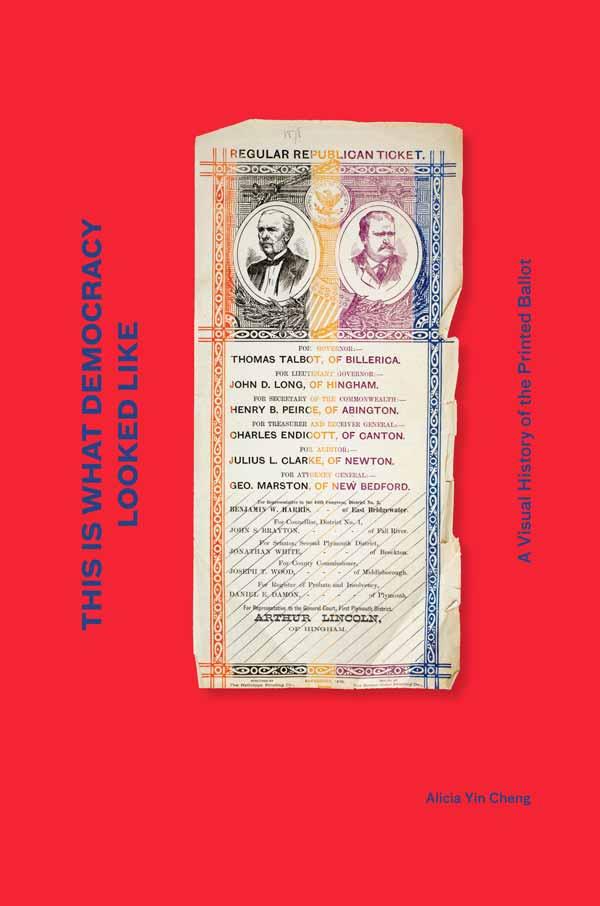

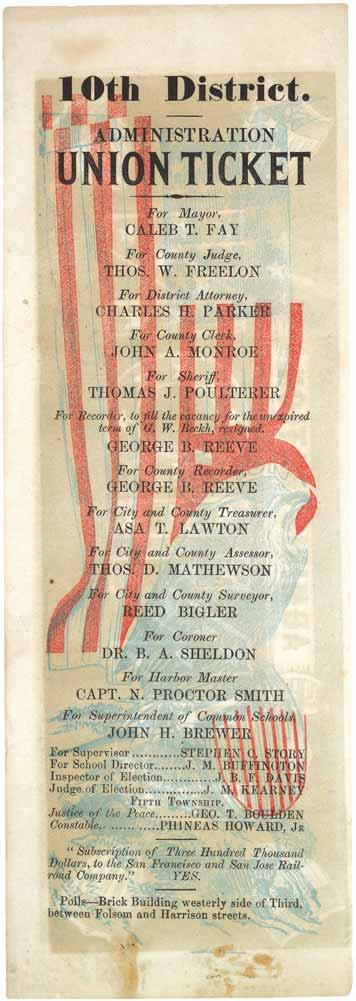

In 2008, when Alicia Yin Cheng stumbled across an article in the New Yorker chronicling the strange, fraught history of American elections, she had no idea that just twelve years later she would be publishing a book on the visual history of the printed ballot. But the article, “Rock, Paper, Scissors: How we used to vote,” by Jill Lepore, mentioned something that changed the way Cheng thought about the history of the electoral process and stuck with her for over a decade: Ballots were colorful.

This one simple fact grew into an in-depth research project culminating in the publication of This is What Democracy Looked Like this past June. In the book, Cheng explores the way the visual design of printed ballots narrates the nation’s political history.