The longevity of the DCP is largely thanks to the generous sponsorship it has received over the years, an unusual feat for a humanities project. Secord recalled with some amazement the time when he and Dr. Alison Pearn, the DCP’s associate director, secured the project’s financial future after finding a major donor. “We had to match the money that we received from this one exceptionally generous donor, and I think he thought it would take several years,” Secord said. But the team was able to build upon the reputation and connections of the DCP’s founder, Frederick Burkhardt, a renowned figure in American humanities. “Effectively, Alison and I went to New York, got into a taxi, made the rounds of the foundations, and raised most of the remaining £2.5 million within the space of a few hours. That was really quite something and doesn’t happen too often in one’s life.”

Drawn from the DCP’s rich materials, the current exhibition at CUL, Darwin in Conversation: The endlessly curious life and letters of Charles Darwin, reveals the project’s strengths. The DCP’s emphasis on capturing both sides of the correspondence—i.e., the letters both to and from Darwin—“really brings out the dialogic nature of the work he was doing, and that can be seen at the heart of his most famous works,” said Secord. For him, some of the most interesting letters are those to and from other members of the Darwin family, which round out the better-known scientific conversations.

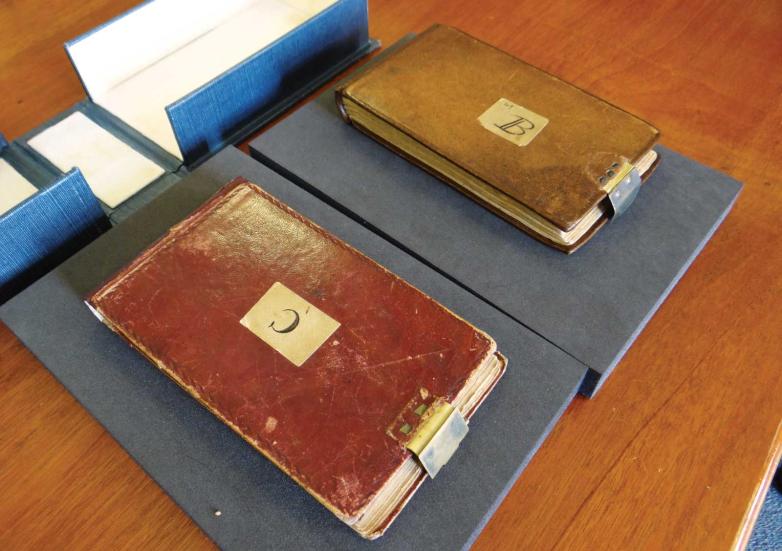

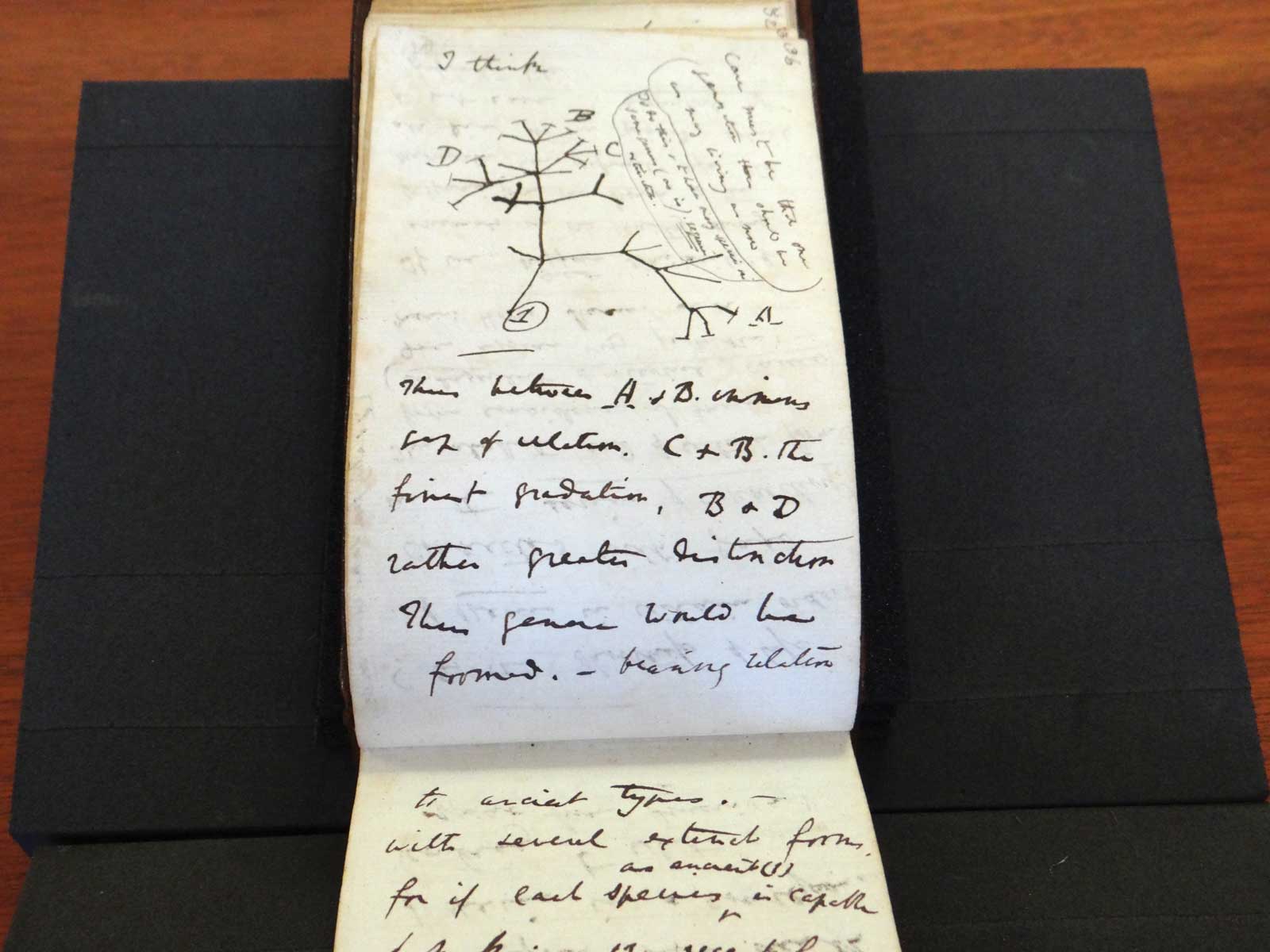

A late—and quite amazing—addition to the Cambridge exhibition are Darwin’s notebooks that recently reappeared on the office doorstep of University Librarian Dr. Jessica Gardner, in a gift bag, with a note whimsically wishing her a happy Easter. The importance of the two notebooks, which include the iconic ‘Tree of Life’ sketch of 1837, “is very difficult to quantify,” she explained. “They are sacred texts in the history of science, particularly of the life and environmental sciences.”