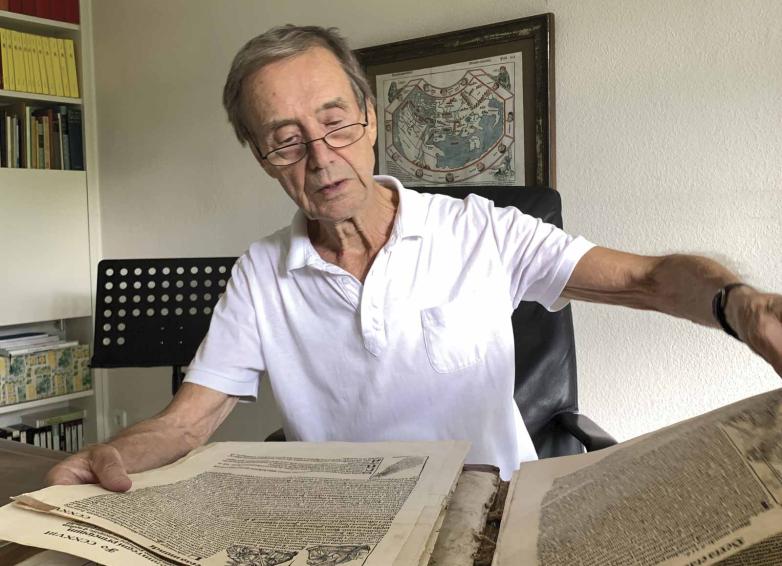

A renowned journalist and author, von Lojewski was the face of political and world news for a generation of Germans. He said he caught the “rare book bug” in 1977 in Washington D.C., where he was covering the presidential election. He had entered a bookshop to search for current political literature and emerged from it with a work on the Holy Land published in London in 1623. “I acquired it like a work of art, a message from a distant past, in order to immerse myself in it at leisure and learn what concerned our fellow humans 300 years ago,” he explained. In his even more intensive and protracted engagement with the Chronicle, he recognized, across the divide of half a millennium, the concerns, hopes, and fears of a world in flux.

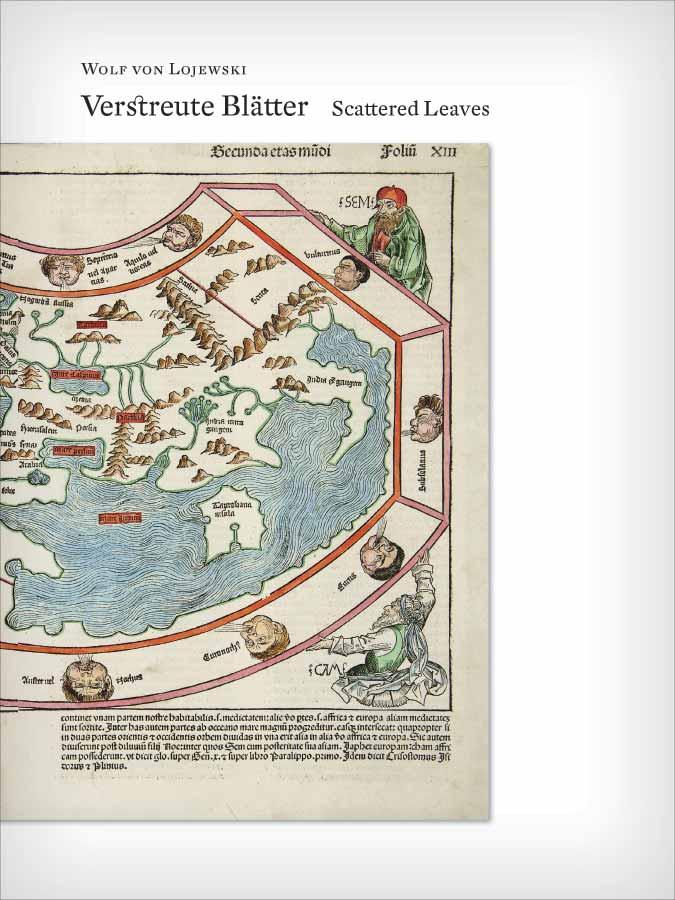

Von Lojewski said that Germans generally consider his search for the 326 leaves “crazy,” and Detlef Thursch, the organizer of the Frankfurt Antiquarian Book Fair who encouraged von Lojewski to write about his collection, confirmed that, in his experience, leaf-by-leaf collecting is uncommon in Germany. Whether you consider his quest eccentric or ingenious, through his collection von Lojewski gained new insights into early printing. He writes about these engagingly in Verstreute Blätter/Scattered Leaves. Readers knowledgeable in German will derive much pleasure from the author’s elegant style (while the English translation tends to be literal at the expense of idiom), and the volume, like the work that inspired it, is beautifully illustrated. With this publication the ‘von Lojewski Chronicle’ establishes itself as an object in its own right, which is more than the sum of its parts: an act of reunification in a world at risk of fragmentation.