But around 2008, Levy was looking for a new challenge. “I’d come to a point where I wasn’t happy doing design and bookbinding for other people,” she said. “I needed to do something meaningful for me.” When she moved to Sigtuna, north of Stockholm, Levy received what she needed: free public access to an art studio and nine months devoted to the new craft she would invent there. “That was the starting point,” she said.

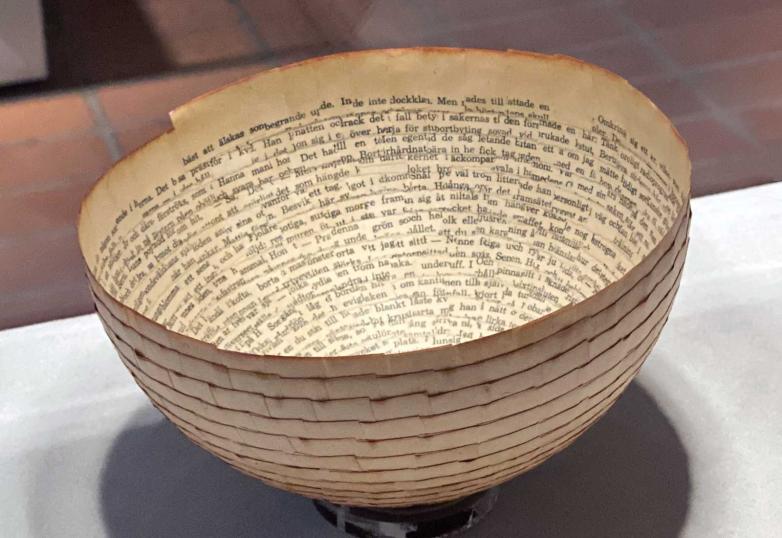

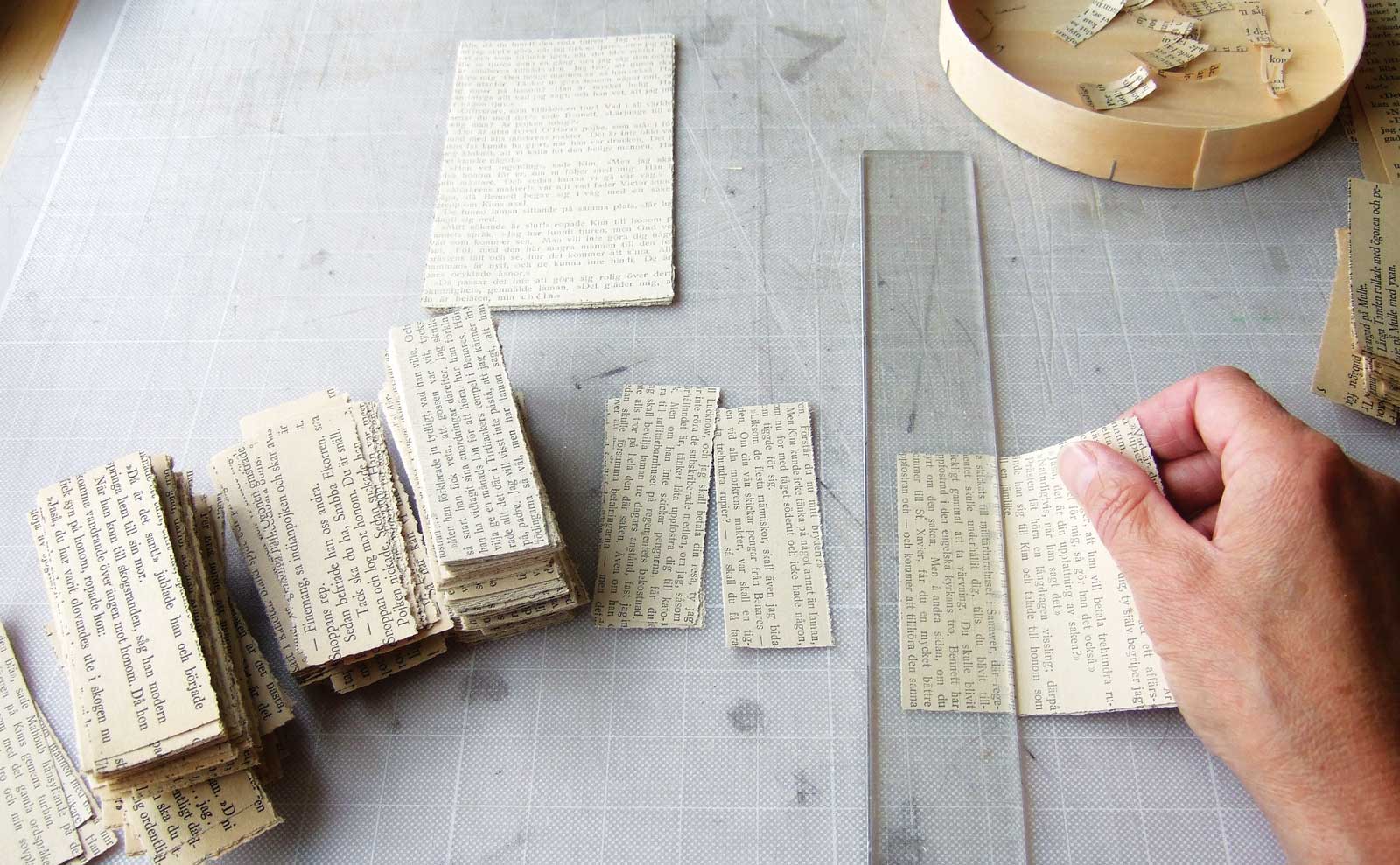

Her experiments drew from her years as a bookbinder. “I shred the pages and merge them using wheat starch paste, molds, and papier-mâché,” Levy said. This technique created intricate paper bowls woven together from text fragments. “I knew I’d found something I wanted to investigate further,” she said.

And she has investigated further since 2009, still using her bookbinder’s bone folder, tweezers, and paper knife. She lives in Sigtuna but rents a studio in the Ateljéföreningen Hospitalet in Uppsala. Her artworks are in the permanent collection of Sweden’s Nationalmuseum and have been showcased throughout Europe. This year, her sculptures were featured at the Homo Faber exhibition in Venice, Italy.

Wherever they appear, Levy’s creations begin and end with paper. “As a bookbinder, I learned the grain of paper, how it works when wet and how it shrinks,” she said. “I couldn’t do what I’m doing now without that knowledge.”

Her most recent artworks home in on content and meaning. Levy calls these sculptures “fantasy plants:” papier-mâché flowers and bulbs mounted to the sticks she collects in the forest near her home. “I’d never known what to do with them,” Levy said. Not until she found a 1933 copy of La vie des atomes by A. Boutaric in a Paris book box, whose contents inspired the fantastical flowers. “I’m combining wood with paper, which was once wood,” Levy said. “It goes back to their roots, which is what the book does by describing how we’re all made up of atoms.”

Usually Levy doesn’t foreground a book’s subject or substance. “That comes last,” she said. But she can’t ignore it either—she’s a reader. “It’s always interesting to me, because the content can always add more meaning.”