Niffenegger returned several years later, this time to teach. Now, she holds the keys to the Harley Clarke, having recently entered into a long-term lease with the city. The visual artist and writer, well known for her bestselling novel, The Time Traveler’s Wife (2003), is busy at work on something different, though no less personal: developing the Harley Clarke into a nonprofit center to teach and promote book and paper arts.

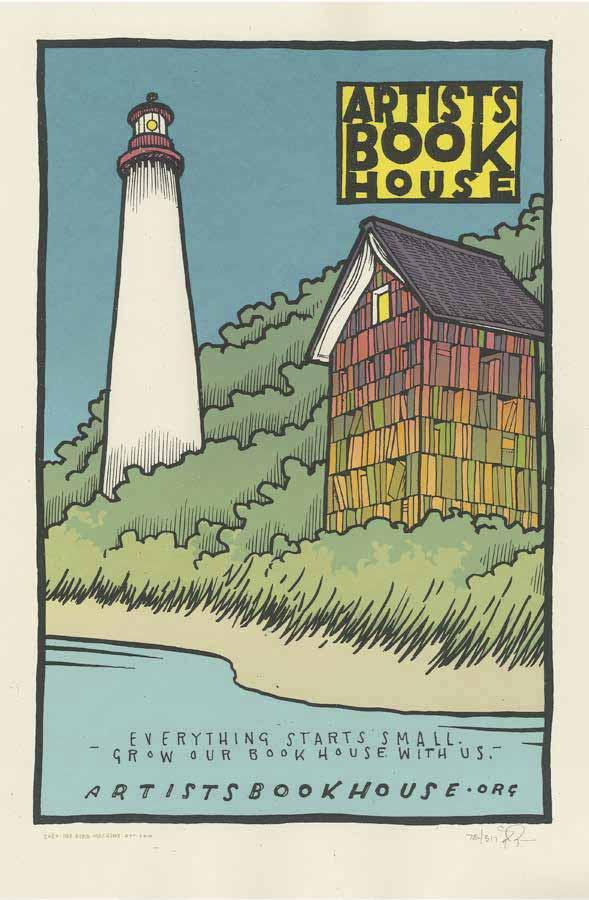

Called the Artists Book House, the arts hub will occupy the landmarked, 22,000-square-foot house, with studios, classrooms, and communal spaces spread across its four floors. The former main bedroom will host a bookbinding studio; the old living room, a bookstore; and the solarium, a cafe. Papermaking will occur in the conservatory, designed by Jens Jensen, the property’s original landscape architect, with pulp beating and cooking in the labyrinthine basement.

“We’re creating a place for people to be,” Niffenegger said. “The cafe means that you don’t have to take a class to be here. You can be in a beautiful building for the price of a cup of coffee.”

Though Niffenegger has a clear vision for the center’s programming—from a young poets club to workshops on letterpress printing and Ethiopian or Japanese bookbinding—it may be five years until Artists Book House officially opens. The Harley Clarke was built in 1927 for its namesake, a utilities tycoon, and was one of the last grand residences to be built along the lakeshore’s prime real estate before the Great Crash. But over its lifetime, the wood-framed and limestone-clad structure, designed by architect Richard Powers, has been neglected. It requires extensive repair, from its vine-covered exterior masonry to its cracked and water-damaged plaster walls, ceilings, and finishes.

With its lavish layout boasting a coach house and servants’ quarters, the Harley Clarke has historically worked well for group use rather than as a single-family residence. In 1950, the Clarkes sold the property to Sigma Chi to use as its national headquarters; the fraternity left in 1965 and sold it to the city, which leased it to the Evanston Art Center. In 2013, the Art Center relocated one mile west, and the Harley Clarke has since sat vacant.