Lessons in Bad Behavior from Ancient Greece: A New Translation of "Characters" by Theophrastus

If there's anything new to learn from Characters, a series of personality portraits written by the ancient Greek Theophrastus (c. 371 - c. 287 BC), it is that gluttons, chatterboxes, drunks, idiots, and others are not unique to any time or place in human history. This robust little volume of character sketches has been widely published and translated since its first appearance twenty-three centuries ago--Jean de la Bruyère's Les Caractères (1688), Character Writings of the Seventeenth Century (1891) and the Loeb Classical Library's edition are a few that come to mind--but each translation is an interpretative undertaking, meaning there is always a renewed need for fresh viewpoints.

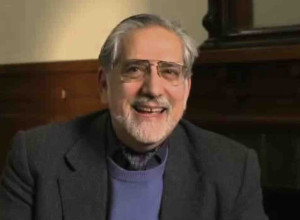

On October 1, Characters will be once again published in English, this time by Callaway Arts & Entertainment. Translated by Pamela Mensch with vibrant pen-and-ink illustrations by acclaimed caricature artist André Carrillo, this edition includes insightful annotations by Bard College classics professor and Guggenheim recipient James Romm.

Part the enduring appeal of Characters is that bad behavior, however caustic, is, whether we like it or not, universal; who doesn't know a busybody who "stands up and promises what he can't deliver," a slovenly fellow "afflicted with dull-white eczema and black fingernails, go[ing] about saying that these illnesses are hereditary," and the friend of scoundrels who "fraternizes with men who have been defeated in court and convicted in public trials; he assumes that if he's friendly with them, he'll become more worldly and formidable."

"These are flesh-and-blood people, with very familiar flaws and foibles," Romm explained. "They remind us that ancient Greeks were actual human beings, not marble busts. The past no longer feels like a foreign country. It's a true gift to be able to 'feel' the reality of the classical world." As Romm points out in his introduction, some previous translators could not square with the lack of judgement in Theophrastus's sketches and inserted their own. This edition strips away those addendums, allowing the original descriptions to be read on their own merit.

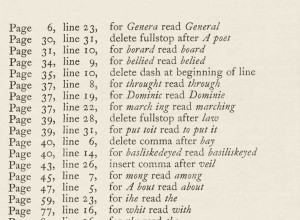

And yet, English-speakers don't suffer for lack options: Penguin released a paperback version as recently as 2015, so why a new translation now? "There's a very practical reason," Romm said. "The Greek text of Characters is rather messy, with lots of sentences in dispute (or simply unintelligible) due to copyists' errors in the transmission process. Only a few years ago, a new edition of the Greek text by James Diggle sorted out many of these problems. This new English version by Pamela Mensch takes advantage of that cleaned-up Greek text."

Contemporary readers may be familiar with Theophrastus's exhaustive Inquiry into Plants and Causes of Plants. However, Characters reveals more of the author's natural verve and wit, which has led some scholars to dispute whether Theophrastus deserves the attribution. "The contrast between Characters and the botanical works is indeed sharp," Romm said. "Assuming Theophrastus wrote both, he seems to have wanted to take an occasional break from science to compose light satire, and perhaps, like all good teachers, sought a way to bring some levity to his 'classroom' -- in his case, the Lyceum, founded by Aristotle."

We may see a bit of ourselves, our friends, and our political leaders in these portraits, but how might have an ancient Athenian reacted? After all, these were sketches based on actual people Theophrastus encountered on a daily basis. Romm believes the Greeks would have taken it in stride-- "With a laugh and a nod of recognition, and probably a bit of embarrassment!"

Society needs writers who document human behavior, even if that behavior never seems to change. But those records needn't always be gloomy. "Thucydides famously wrote that human nature is constant over time, so that the deeds he recorded in the Peloponnesian War would be seen again," Romm said. "In his case, that's a tragic message, since he mostly records atrocities. Theophrastus supplies the comic side of the same equation."