Collector or Custodian?: Saying Goodbye to A Unique First Edition

Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue by Captain Francis Grose

I bade farewell to the Captain today, writes slang lexicographer and author Jonathon Green. Captain Francis Grose, militia officer, antiquarian and slang collector. We have been sharing a home for some years, but it had become time to let him move on. Others requested his presence. I am ever-older and he, ageless, should be made available to illumine a wider world. So be it.

Were that world also perfect we should have been ensconced in a fine God permit, ever-faithful Tom Cocking on the box, bottle of red fustian to hand, a rump and dozen to assuage the Captain’s laudable appetite, rattling onward from the Start to the Relish, the Holy Land to the Bow-Wow Shop, and on to Swell Street as cits and loblollies raised their tiles in his honour, gentlemen of grease applauded their carnivorous patron, rum bluffers tossed off a toast (no heeltaps!) and Madame Van and Miss Laycock winked winningly from behind their fans.

But this not a perfect world, it seems if anything to be a world groaning out its terminal throes – and best it should, perhaps – and I was forced to subject the finest slang lexicographer of the 18th or even any other century, to the squalor of public transport, bus, tube, all that the Wen can offer and so little of it desirable.

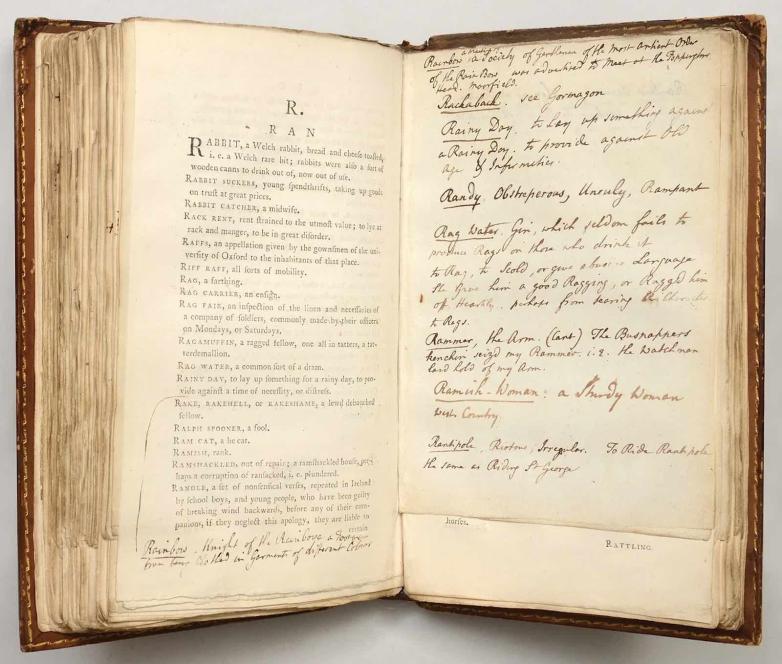

Nor, this being 2023, was it the corporeal Captain. He left us, too early by far, in 1791. But the Captain in libro, in the pages of the first edition of his Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue. This, a dictionary of slang (‘better left unpublished’ sneered one snob obituarist), appeared in 1785, and there would be revisions in 1788 and 1796 but the one I carried is unique. It offers dozens of interleaved pages, handwritten by Grose himself, laying out the bases of the entries that would be added to or would revise those existing and appear in the second edition. Or nearly all. Some seem to have slipped between his or his printer’s fingers, some e.g. arse-man, seem to have been deemed a little too vulgar and failed the cut; this particular term would not reappear until 1941. (I have written of them here: https://jonathongreen.substack.com/p/the-too-vulgar-tongue and of the Captain himself here: https://jonathongreen.substack.com/p/fit-for-purpose).

The book is thus one of a kind. With its creator dead, it seems to have entered the world via Grose’s printer Samuel Hooper who in turn left it among his personal library to his own family and thereafter it returned to the trade. Other than my own there are two bookplates, plus a grand colophon stamped into the cover. Its motto reads: Sub Tegmine Fagi and comes from the first words of Virgil’s first Eclogue, ‘Tityre, tu patulae recubans sub tegmine fagi’. The line had long since given a name to a 17th century gang of well-to-do roughs - the Tittery-tus - who infested the London streets, committing their crimes for amusement rather than gain. The tag implied that these privileged rogues were men of leisure and fortune, who ‘lay at ease under their patrimonial beech trees’). We must accept that chronology makes this no more than coincidence.

In 2013 a friend on what was then Twitter alerted me to a bookseller’s catalogue. There, in all its glory, and at a price that was surely beyond anything I could even ponder, was the Grose. I showed my wife. "You should have it", she urged. I did not ask twice. Yes, there was enough dosh in the kitty. It was just…so much. I rang, they sent me pictures of the juicier ms pages. I need no further prompting. The deal was done, even if in my excitement I initially offered a cheque on a defunct account.

Never for a moment did I see the book as ‘mine’. I was its hugely privileged custodian, ‘thine host’ as it were. I have been for the last decade. I have transcribed virtually every ms entry into Green’s Dictionary of Slang and they can be researched there. For the ‘real thing’ I am told that the journey may henceforth have to be somewhat longer. Fortunately a number of scholars have accessed it while I was still chatelain. Among them one who said that while Grose did not restrict himself to one note-appended edition, the alternative example, in the British Library, was but a precis. The Captain who was pausing amid convivial, like-talented companions on my shelves ruled.

But the volume to which I played host was not merely a first edition, and to be treasured as such. It was, it is a tangible link between myself and a man I see as one of the finest of my predecessors. We are not many, nor do we leave much in the way of tracks. Most of those who hunt down the counter-language barely leave a name and that almost grudgingly. Working on the margins, amassing and publishing the substance of a marginal lexis, they remain marginal figures. We have the odd letter, we have, to my knowledge and even now, no other manuscript of this length.

Captain Grose, both literally – he was a solid figure much petted by butchers – and figuratively too – three-dimensional in every sense – is an exception. He is the first of us to leave a portrait, several in fact. Perhaps the supposed biography that stands as preface to Pierce Egan’s update of the Classical Dictionary which appears in 1821 is at times imaginative, perhaps it is pure fantasy. Though why? Egan was his era’s leading sporting journalist, his work was elaborate, such was prize-fighting’s pleasure, but no-one says it lied. No matter. Grose was a known London character. He knew Samuel Johnson, and unlike the Scotland-scorning Doctor, was cherished by Robert Burns. He was admired for his antiquarian exposition. And for those who appreciated such things, there was his dictionary, vulgarity notwithstanding. For me the Captain was a legendary figure. Let us honour that.

And for a decade I have had the joy, to me the privilege, to have his work, the fruit of these researches of 237 years ago, those walks on the linguistic wild side of the late 18th century metropolis, as my companion. It has sat with its peers in my small collection of slang dictionaries. Primus inter pares. The capstone of the personal and professional wall those dictionaries represent.

Thank you, Captain. I shall miss you.

This is a guest post courtesy of Jonathon Green who writes the Mister Slang newsletter on Substack where a version of this article first appeared and Green’s Dictionary of Slang, the largest historical dictionary of English slang.