How Photographic Innovation Brought Edward Curtis’s Images to Life

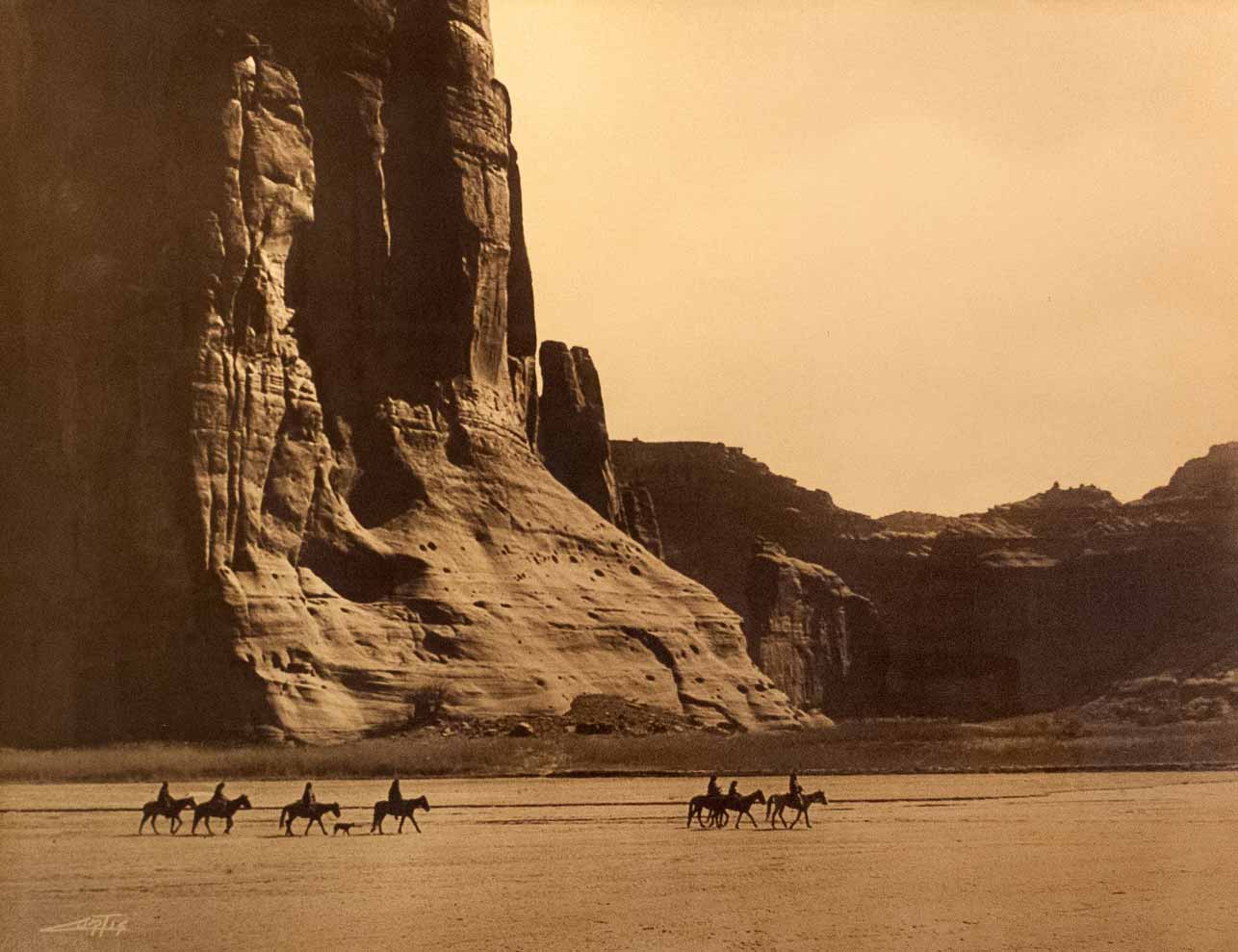

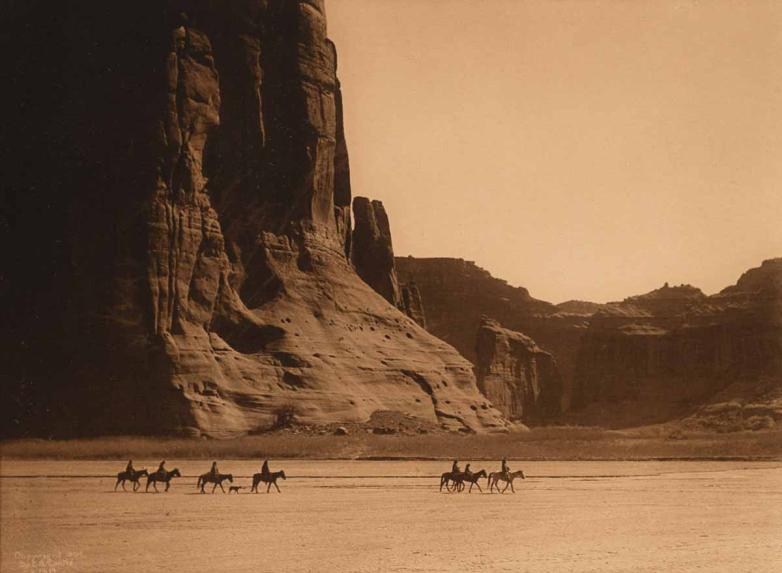

Canyon de Chelly, 1904. Gelatin silver border print.

Sponsored by Christopher Cardozo Fine Art.

Mr. Curtis, because of the singular combination of qualities with which he has been blest, and because of his extraordinary success in making and using his opportunities, has been able to do what no other man has ever done.

-Theodore Roosevelt

Though photographer and ethnographer Edward Curtis’s The North American Indian is an iconic work in the American historical canon, Christopher Cardozo, an Edward Curtis scholar, estimates most people are only familiar with 2–5 percent of Curtis’s work.

“Hundreds of Curtis’s vintage photographs have never been reproduced and, therefore, remain largely unknown,” Cardozo said. “This is even more true for the more than two million words of superb ethnographic text and transcriptions of language and music. Thus, while Curtis may be the most widely exhibited and collected photographer in the history of the medium, a great deal of his oeuvre remains largely unknown.”

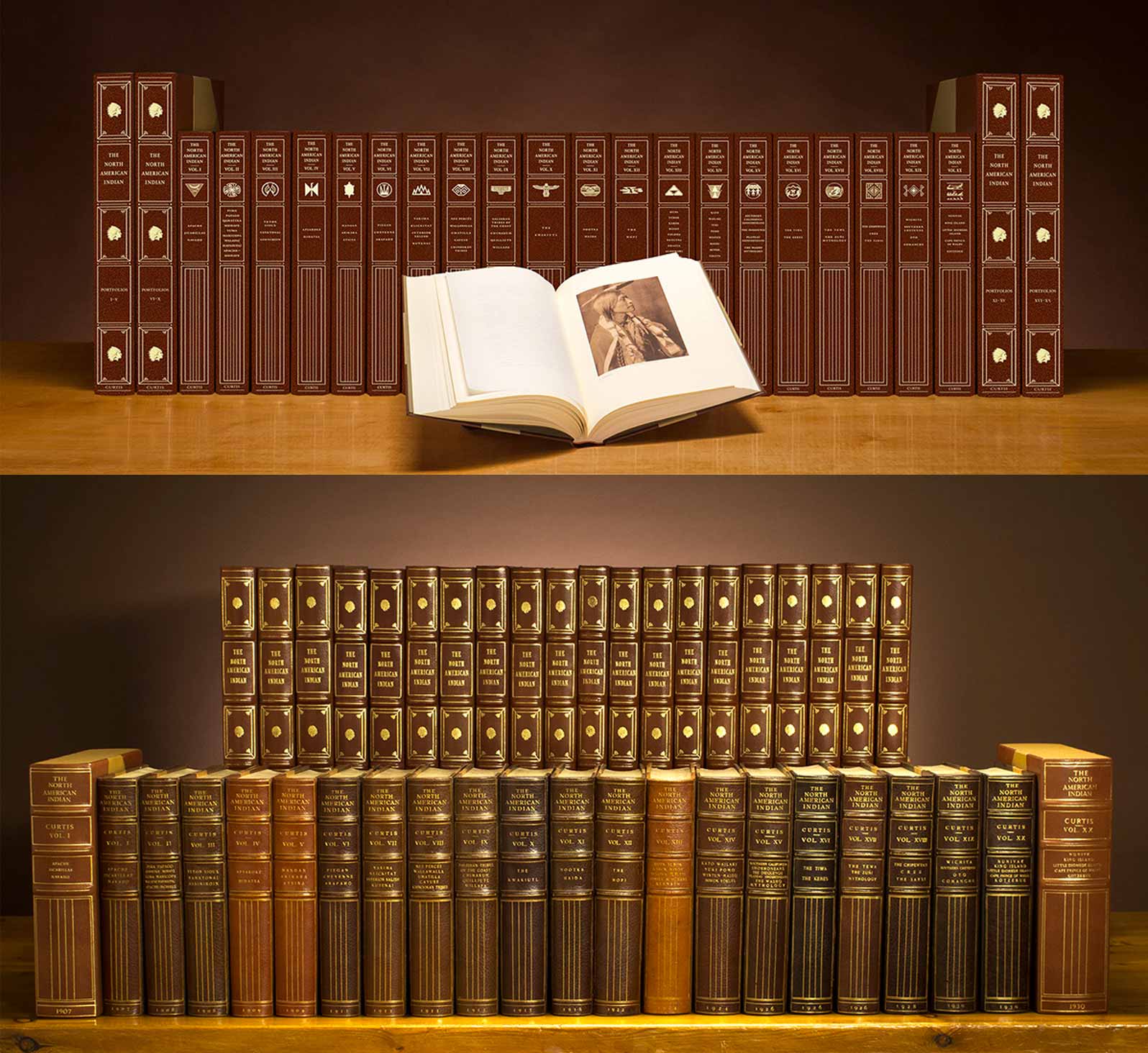

This is part of the reason why Cardozo, a photographer and historian himself, has undertaken the monumental task of recreating The North American Indian, a twenty-volume, twenty-portfolio set of books. Cardozo tripled his staff and invested over $1,000,000 for this republication. The “Custom Limited Edition” version involved thousands of hours of hand work and complete sets now reside at The Morgan Library and at Harvard University. Cardozo has recently released a more affordably priced “Complete Reference Edition”, which is identical in content to the Custom Limited Edition. The “Complete Reference Edition” is beautifully and durably produced but was not hand assembled and bound. Cardozo hopes that in doing so, not only will Curtis’ remarkable scholarship will be more accessible to the public, but collectors and art enthusiasts will become more familiar with Curtis’ skill and dedication to his craft.

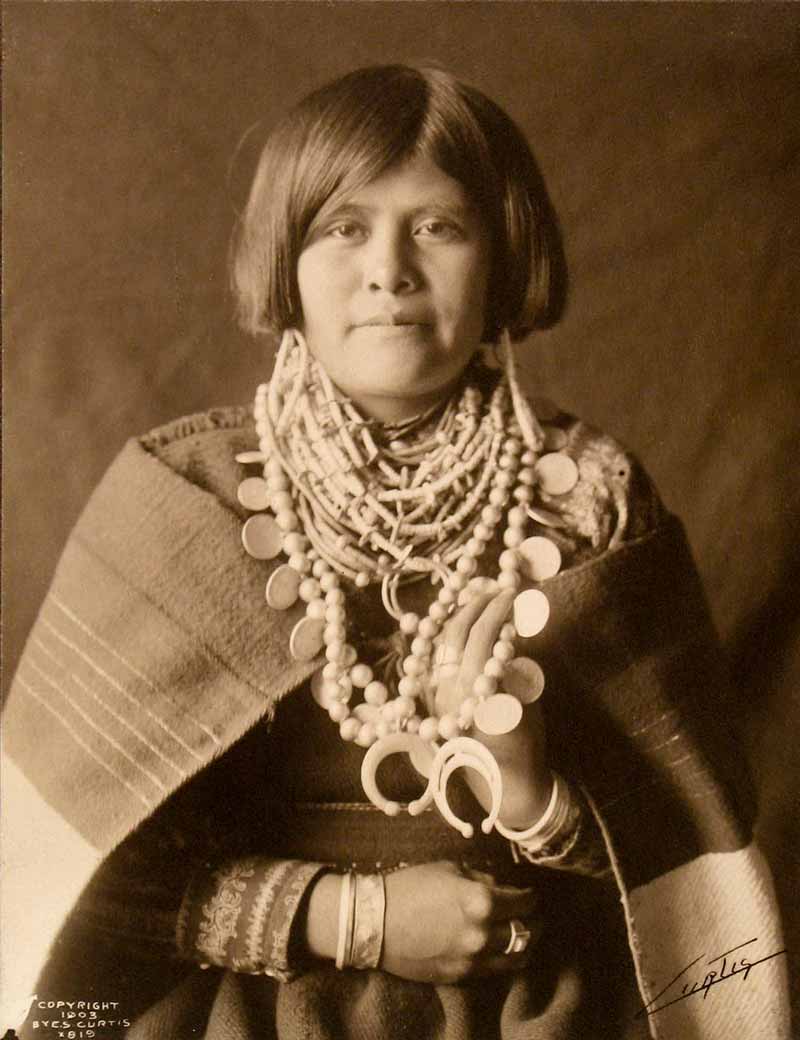

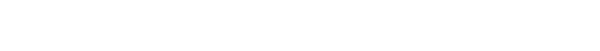

Never compromising in quality, Curtis is known for his haunting images of Native peoples. Part of what makes his images in The North American Indian stand out is that they are exceptional photographs, produced using the time-consuming photogravure method (a form of photo-engraving), etching the image onto a copper printing plate, and then producing the print with sepia-toned ink. This method allowed Curtis to produce rich, finely detailed images. Cardozo said Curtis “humanized Native people for the American public, who were unfamiliar with Native Americans beyond the typical stereotype of ‘savage,’ and thus helped to change public opinion about America’s First Peoples. Had he merely documented the sorry plight of Native people at the time, Cardozo believes it would have simply reinforced the public’s already negative beliefs about Native people.

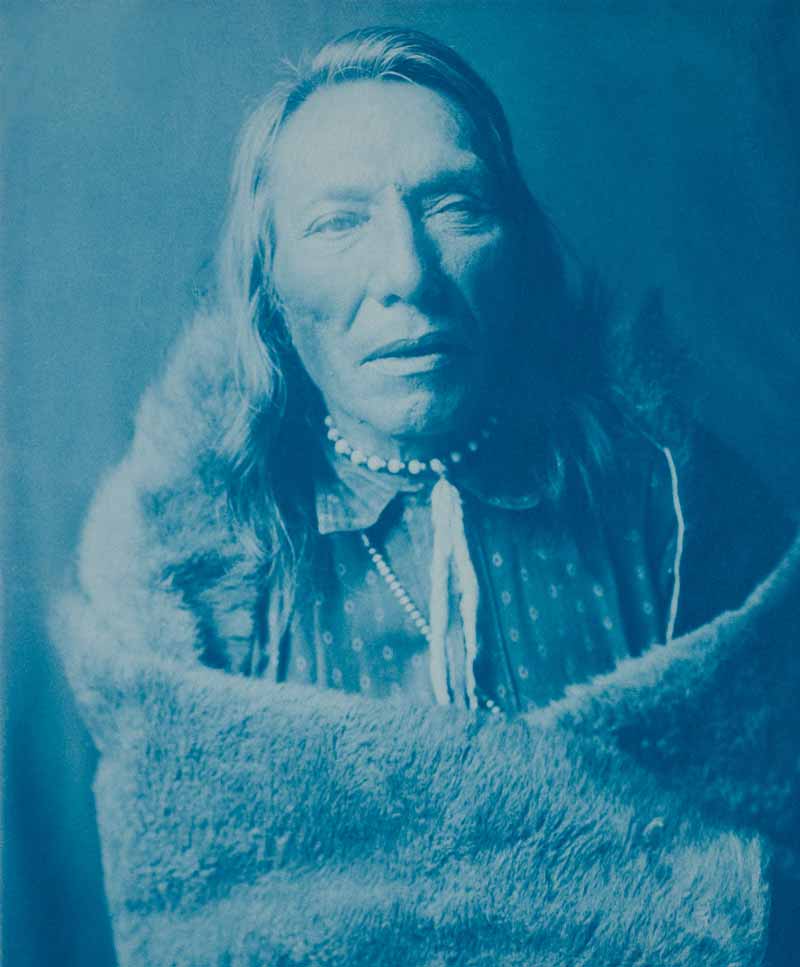

Curtis was also an innovator, who pioneered the “goldtone” method, (also called the “orotone” or “Curt-tone” after “Curtis”). This method produced luminescent, three-dimensional photographs by suspending the image on a glass plate and then backing with a gold liquid wash. Curtis was famous for this process, often winning contests for his goldtone submissions, but he also produced warm-toned platinum prints, gelatin silver prints, extremely rare goldtone paper prints, and cyanotypes, though few of these blue-toned prints survive today.

While Curtis’ photographic mastery certainly makes his work stand out, it was his ability to effectively pair this mastery with his skill in capturing the culture, spirit, and individuality of his subjects that truly sets Curtis’s work apart.

“Most photographs of Native people at the time were distant, cold and stereotypical,” Cardozo said. “Curtis created warm, intimate images that often brought us much closer to the individuals and who they really were, in a way no other photographer was able to.”

To learn more about the various photographic methods Edward Curtis employed and its effects, view our slideshow or read more about how the republication by Christopher Cardozo Fine Art is introducing The North American Indian to new audiences.