When Japan Went West

How fabric-like books of fables and folktales brought East Asian culture to the world

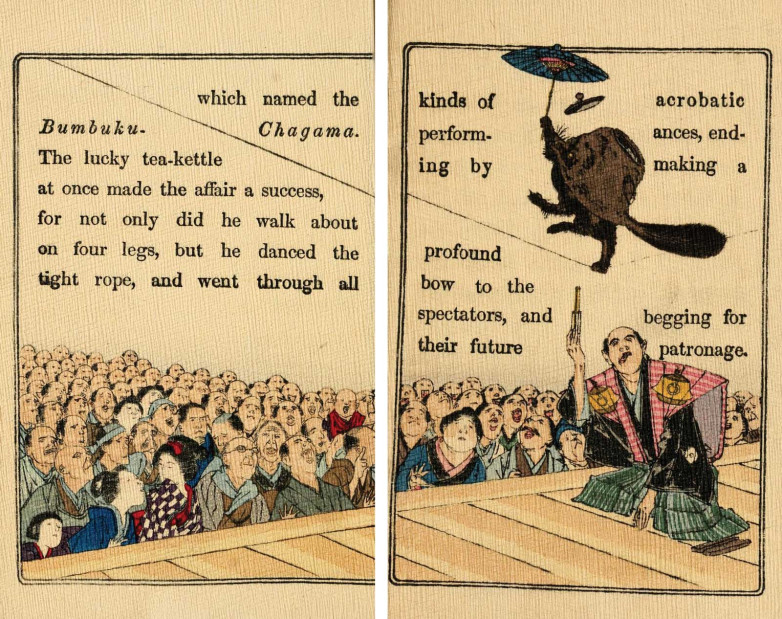

Only a moment earlier, the talking dog-like badger was a tea kettle. Now, the magical animal—still part kettle—is smoking a pipe while casually negotiating a work arrangement with a tinker (a mender of household objects): “I will bring luck to anyone who treats me well. … I like nice sweet things to eat, and sometimes a little wine to drink, just like yourself.” The tinker agrees, and the two travel around the country as the playful creature performs spectacular shows with acrobatics and tightrope dances. Their fame and fortune grow—both at home and abroad—and eventually the two can peacefully retire.

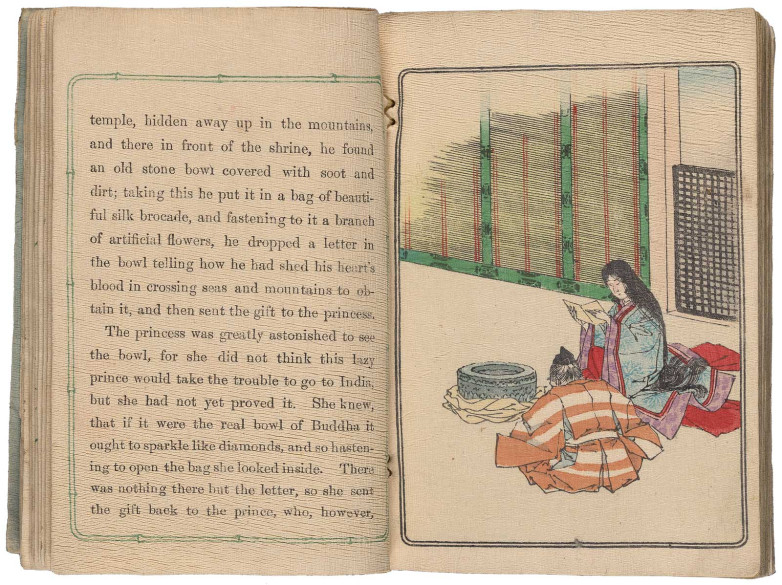

Elegant woodblock illustrations accompany the English-language translation of The Wonderful Tea-Kettle, an enchanting traditional Japanese fairy tale on display in a late nineteenth-century edition at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut. But what will immediately stand out to visitors of Textured Stories: The Chirimen Books of Modern Japan, on view through May 3, 2026, is the crinkly, delicate paper that gives the book its unique appearance.

Courtesy Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

Chirimen-bon, or chirimen books, is its own genre: a specific type of illustrated book produced in Japan between the 1880s and 1950s, created with textured, fabric-like paper. The word chirimen may have its roots in the Japanese word chijime (crinkled), and the term is now frequently associated with crêpe-style silk fabric, but these books are actually made from mulberry paper. To create books, every sheet was meticulously hand-pressed—after printing but before binding—to create a texture that resembles the delicate wrinkles of sumptuous, draping kimono silk.

For this groundbreaking exhibition at the Beinecke Library, curators Haruko Nakamura, librarian for Japanese studies, and Yoshitaka Yamamoto, assistant professor in the Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures, selected seventy chirimen books and related artifacts from Yale University Library, the Yale Center for British Art, and the Peabody Museum, as well as a loan from the Harvard-Yenching Library. The Beinecke Library’s exhibitions program is Yale’s most expansive, dedicated to engaging presentations of rare books and manuscripts. Textured Stories introduces visitors to chirimen books—the stories they tell, how they were made, and the historical moment in which they emerged—while also offering innovative scholarly perspectives on their place in traditional Japanese culture and their ongoing contemporary influence.

If the sweetly illustrated tale of the magical tea kettle seems only charming at first blush, exhibition visitors will soon learn that chirimen books were, in fact, potent vehicles for cultural expression and exchange. After almost 300 years of limited contact with the West, Japan began rushing toward Westernization in the last half of the nineteenth century while simultaneously aiming to articulate its own distinctive national identity. Chirimen books are works of cross-cultural collaboration that emerged within this context of rapid transformation.

Often presenting Western-language retellings of traditional Japanese stories, chirimen books are enhanced with woodblock illustrations that follow East Asian art historical conventions. An international network of translators, artists, printers, and distributors brought these books into existence for an equally cosmopolitan readership. A noted textbook publisher initially produced the books—created to aid Japanese learners in their study of Western languages—in English, French, Spanish, German, Swedish, Russian, and other languages. Western tourists to Japan collected chirimen books as souvenirs, and eventually, they were exported to Europe.

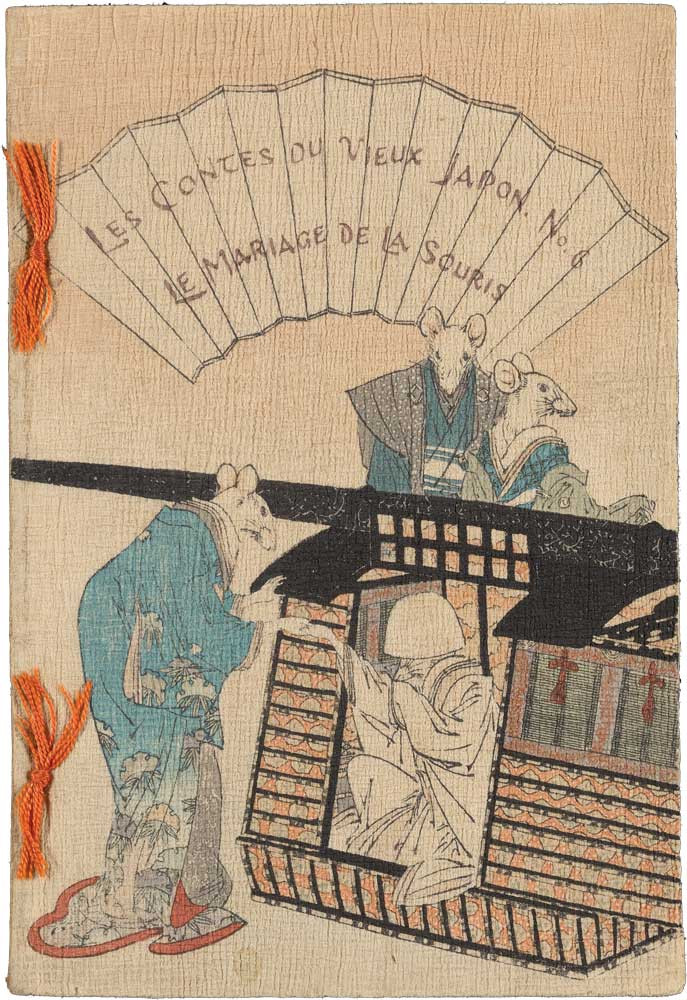

Chirimen books joined together Eastern and Western cultural traditions—on the page and through the cross-cultural collaborations that brought them into existence. As much as they may have helped Japanese language learners or been read as children’s stories, they also shed light on details of Japanese culture that would have previously been largely unknown in the West. In The Wonderful Tea-Kettle, for example, readers gain a glimpse of chanoyu, a traditional Japanese tea drinking ceremony. The Mouse’s Wedding, another fairy tale book on view, is a story about elegant mice that nonetheless accurately documents Japanese wedding and marriage conventions at the time.

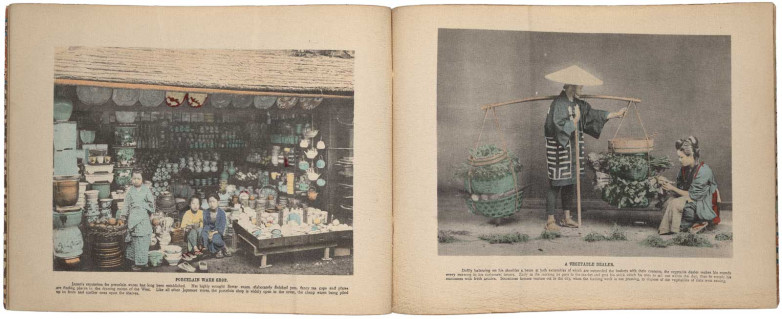

Fables and folktales were especially popular versions of the chirimen genre, but visitors to the exhibition will encounter books with a wide range of stories and styles. Some reflect a historical moment with great directness in a decidedly non-fairy-tale world. Scenes from the Japan-China War, for example, was produced as a commemorative volume marking the end of the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–95). Other works, such as Illustrations of Japanese Life, incorporated newly introduced Western photographic techniques—such as collotype printing (an engraving technique that uses a gelatin-coated glass plate)—and captured scenes from Meiji-era daily life on chirimen paper.

Textured Stories provides a fascinating look at the transformative historical moment in which chirimen books were created, but it also offers a deeply researched perspective on how these works engaged past traditions. The curators paired a seventeenth-century gold-leaf manuscript of The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter—a tenth-century classic and the oldest surviving work of Japanese fiction—with a chirimen retelling. Although the book materials and languages differ, the story in both versions is the same: a bamboo cutter’s daughter is actually a princess from the moon, who rejects marriage proposals from five different suitors and decides to return to her celestial palace.

Traditional chirimen books look back to East Asian literary and art history, but the exhibition concludes by looking forward, toward popular, present-day genres. Contemporary Japanese graphic novels and animated films likewise draw upon older, illustrated Japanese storytelling conventions while also being influenced by Western comics. Just as chirimen books offered late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Westerners an opportunity to learn about Japan, so too do manga and anime invite international audiences into the world of Japanese storytelling today. Readers of manga and watchers of anime will feel quite at home in this exhibition’s chirimen world of spirits and supernatural beings.

The story of chirimen-bon is itself a reminder of the power of cross-cultural curiosity and collaboration. How do traditions transform in moments of great cultural upheaval? What do writers and artists communicate to audiences across time and space? This exhibition invites visitors to reflect on the human drive to connect and explore how storytelling evolves and endures.