These, and many other documents on view, were collected by David M. Rubenstein, a lawyer, businessman, and philanthropist. “The benefit of seeing this particular exhibition is that [it] explains what we celebrate every Fourth of July: the birth of our democracy,” he said. “Not knowing how our democracy came to be makes protecting it difficult.”

The exhibition celebrates the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence by tracing the development of the ideas and beliefs of the American Revolution. Louise Mirrer, president and CEO of the New York Historical, said, “Through historical printings, the origins of the ‘American experiment’ are on display, allowing us to reflect on how we live and fulfill the ideals of our nation today.”

Today is a fractious time. Rubenstein is well aware. “I think in times of division it’s worth remembering how we became a union.” He added, “There are lessons to be learned in how independence was gained. Ideas alone don’t give us our country; we needed shared sacrifice and national cooperation.”

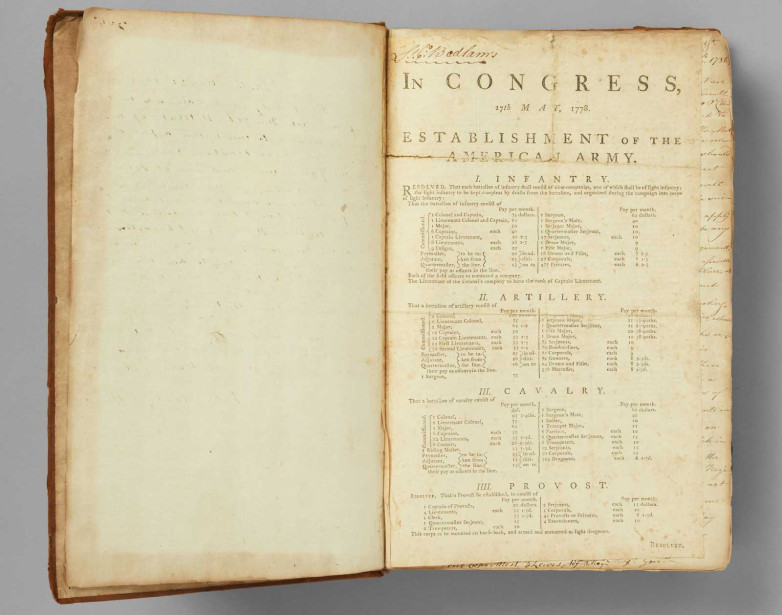

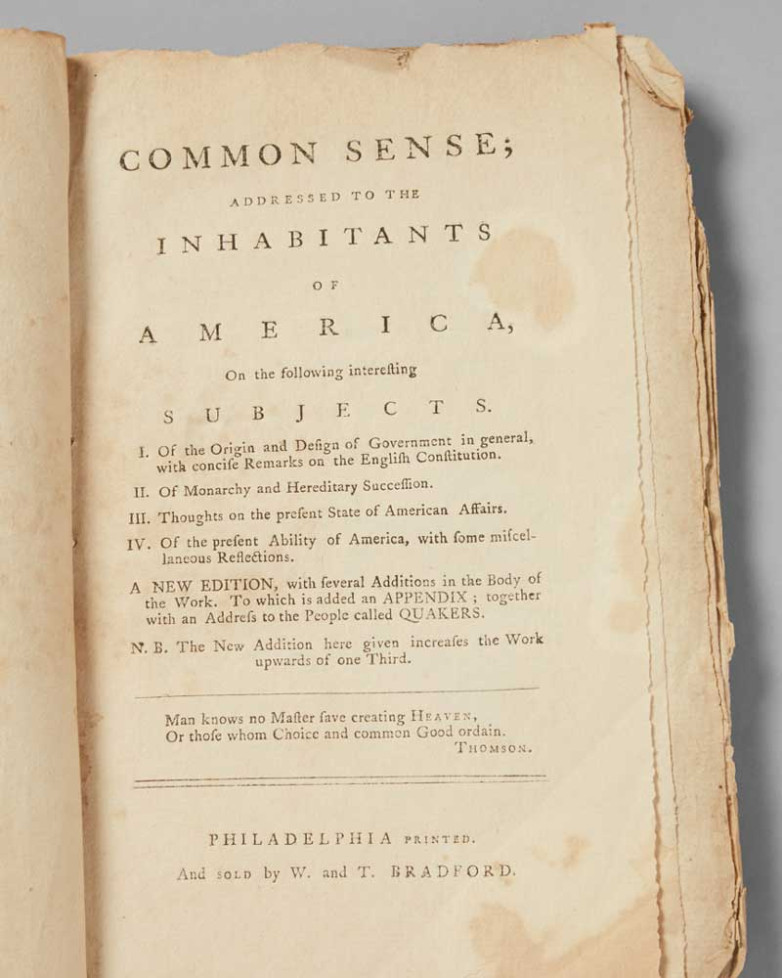

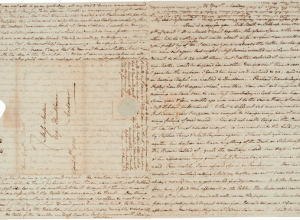

The exhibition starts with the Stamp Act of 1765 and ends with the Articles of the Confederation, adopted in November 1777. Betwixt these foundational documents are significant printed works related to the American Revolution. These trace, said Mirrer, “the emergence of our nation through a shared belief in the power of the people and the promise of democracy.”