Rand McNally did not initially set out to become America’s top map producer. When the founder of the company, William H. Rand, arrived in Chicago from California just after the Civil War, he intended to cater to the needs of the booming railroad industry, printing their annual reports, timetables, stationery products, and tickets. The industry must have been pleased with Rand’s work, because in just three years his ticket printing business alone had grown to 100,000 units a day.

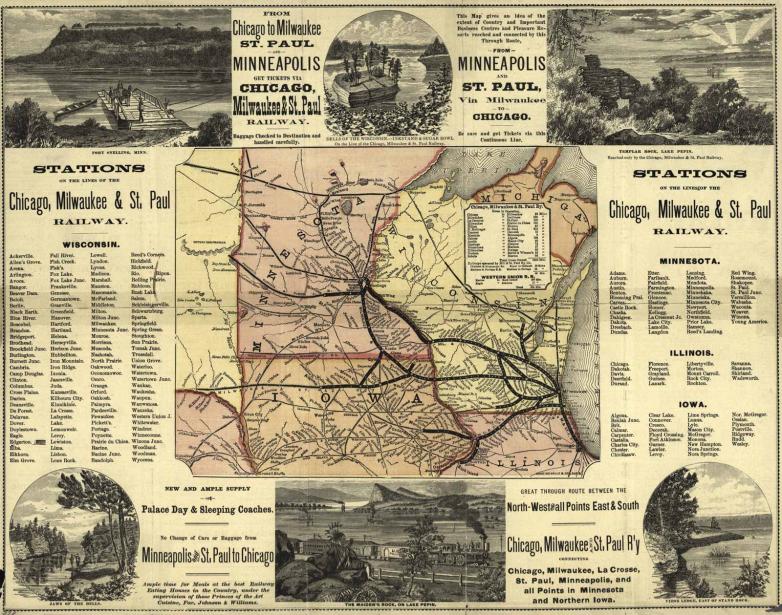

One of the associates that Rand hired to help him with his rapidly growing sales was Andrew McNally, a twenty-two-year-old printer who had recently immigrated to America from Ireland. McNally proved himself more than capable and was soon asked by Rand to become a partner in the firm, along with Rand’s nephew George Amos Poole. With Rand as president, McNally as vice president, and Poole as treasurer, they incorporated their new partnership in 1873 under the name Rand, McNally and Company. They celebrated the new business venture by announcing “to their railroad friends and patrons” that they were expanding their product line to include “Map Engraving in the very highest style of the art.” In less than a decade, the new map department would account for forty percent of the company’s revenue.

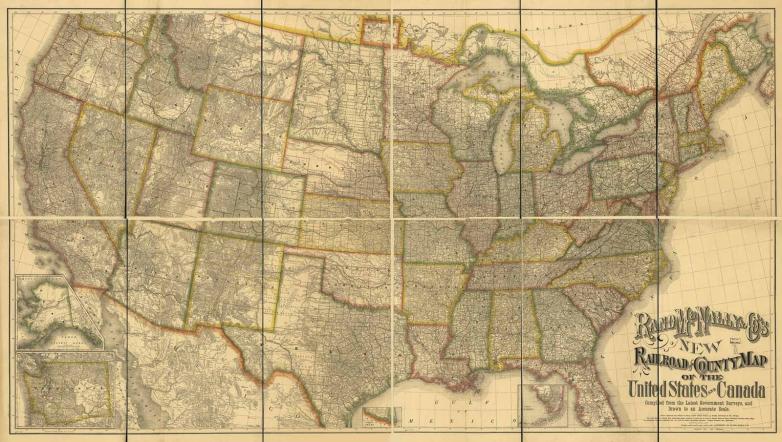

Rand McNally’s map engraving was unlike any other in North America. While most of its competitors were printing from lithographic stones, or incised copper plates, Rand McNally wisely decided to adopt the new wax engraving process (or cerography) developed by Sidney Edwards Morse in the 1830s and 1840s. Cerography used an inexpensive metal plate covered with a layer of hardened beeswax. Engravers removed slivers of wax that would make up a map’s lines and symbols. The waxed plate was then placed in an electrically charged bath of copper sulfate which caused a thin copper coating to adhere to the waxed surface. This coating conformed to all the engraved markings in the wax, and when peeled off, offered an exact replica of the waxed map, but in relief. The copper plate could be used in a letterpress and would be good for a million impressions, sixty times more than what a lithographic stone could produce and about a hundred times more than what could be printed from an incised copper plate. Cheaper production costs meant lower prices for their clients.