A Pilgrimage to Palestine

In "Mark Twain and the Holy Land," the New-York Historical Society celebrates the author’s first novel—and the fabled journey it recounts

While Mark Twain is remembered chiefly for his Mississippi River novels, it was The Innocents Abroad, published in 1869 and almost forgotten today, that made his reputation. No other book Twain wrote sold more copies than Innocents. On display at the New-York Historical Society through February 2, 2020, is a fascinating look at the young Twain on the eve of celebrity in an exhibition that marks the book’s 150th anniversary. Organized by the N-YHS in partnership with the Shapell Manuscript Foundation, the exhibition features a wealth of Twain documents and letters, photographs, artifacts, and books, including the copy of Innocents owned by Twain’s wife, Olivia Langdon Clemens, and the salesman’s sample kit used to sign up subscribers to the volume. Olivia Clemens’ ownership of the book has a special resonance in the show, for it was on the trip described in the book that Twain met fellow traveler Charles Langdon, through whom he met in turn Langdon’s sister, Olivia. Twain also made a special effort to procure a Bible for his mother, and this too is on display in the show.

Courtesy of the Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, N-YHS, Jessie Tarbox Beals Collection

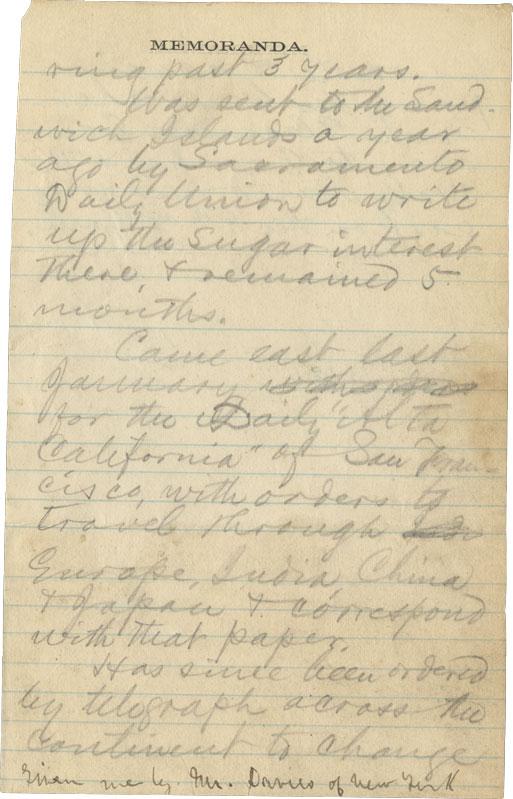

When Twain arrived in New York in 1867, he had a modest reputation as a speaker and a writer of short, humorous pieces for newspapers and magazines. Now he was hungry for a book. He chanced upon an advertisement for a “pleasure cruise” to Europe and the Holy Land. The voyage was to feature an “A list” of political and social notables. Twain knew he had to book passage on the ship—not to see Europe and the Holy Land so much as to rub elbows with the wealthy and powerful who might be useful for him. He persuaded a San Francisco newspaper to underwrite a ticket, in return for which he would send back a weekly column from the journey. But reality quickly mocked Twain’s expectations. Instead of notables, he found himself largely in the company of respectable, middle-class Protestants. They became objects of satire for Twain, who preferred to play cards, smoke cigars, and drink wine with a few reprobates like himself.

The voyage of the Quaker City, the pleasure ship that carried these pilgrims across the Atlantic, was well documented, some of which can be seen in the exhibit. As the first example of organized tourism in America, the voyage included a photographer, William E. James, whose camera and images are on display. Also on view is a contemporary oil painting of the Quaker City, the passenger manifest, Twain’s correspondence, and a Dragoman costume that Charles Langdon brought back from the Ottoman Empire.

Courtesy of Randolph James

Courtesy of the Shapell Manuscript Collection

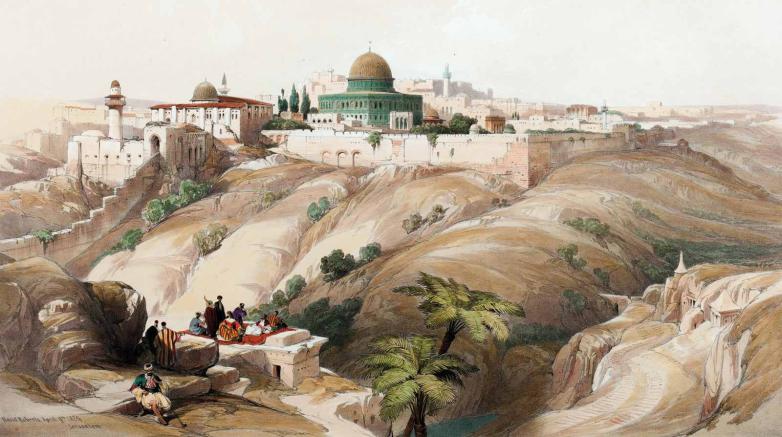

The highlight of the voyage was the Holy Land, a place held in awe and reverence by American Protestants raised on the Bible and nourished by travel books that described it in terms of an epic romanticism. As a Protestant himself, Twain brought the same baggage with him; but unlike his fellow pilgrims he found himself confronted with an altogether disappointing reality. And he turned that disappointment into biting humor, mocking everything from the needy beggars, shepherds, and nomads to the diminutive scale of things to the mountebanks and the phony holy sites and relics they had to offer. This was Twain’s contribution to the shaping of an American character: the American traveler, the person who saw the world clearly and for what it was, without the aid of tradition and the “authority” of guidebooks.

While Innocents can hardly be said to be a recommendation to visit the Holy Land, the burgeoning popularity of its author undoubtedly contributed to widespread interest in touring Palestine. Letters from such notables as Ulysses S. Grant, William T. Sherman, and Theodore Roosevelt—pilgrims all—document that interest, and they are on display. In 1876, Herman Melville finally published his enormous Clarel: A Poem and Pilgrimage to the Holy Land, based on a trip he made to the Holy Land in 1857. Like Twain, he found the place wanting: “a caked, depopulated hell.” But there was no humor in Melville’s account; Clarel recounted a failed pilgrimage to recover religious faith. The two-volume work is present in the show.

Lenders to the show include Susan Tane; the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley; Cornell University Costume Textile and Library Collection; Brooklyn Museum; Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University Libraries; and Vassar College Library.