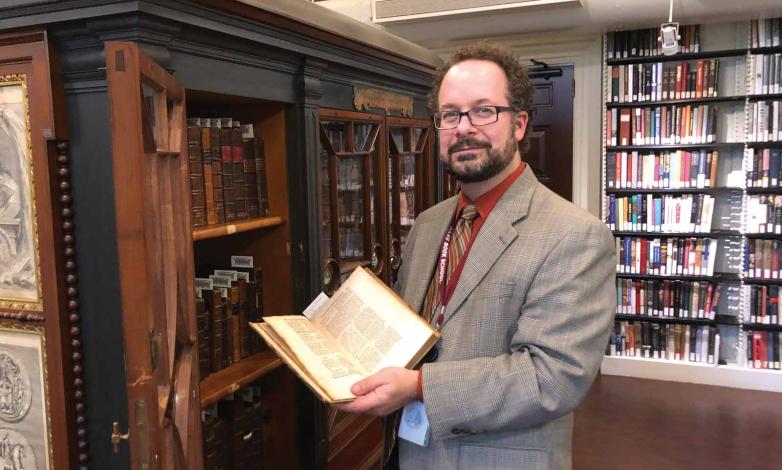

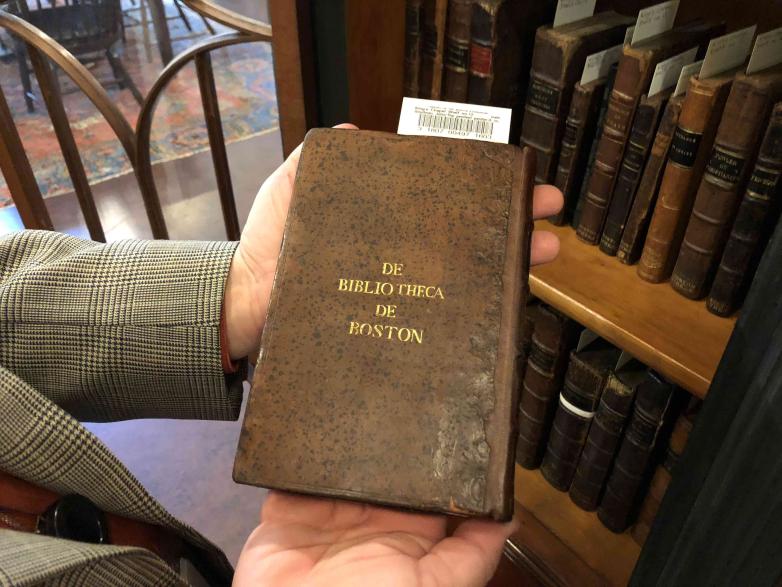

The books circulated from King’s Chapel until the Revolutionary War, when the loyalist clergy fled the city and the library disappeared into safekeeping. It reemerged in the early nineteenth century and was deposited at the Athenaeum in 1823. Fifty years later, the King’s Chapel congregation sponsored the creation of an ark-like Colonial Revival bookcase in which the collection is still housed. All are exceptionally well-preserved and many retain the original bindings Bray commissioned to identify them as part of the library.

Conscious of the fact that the King’s Chapel collection expresses a very particular approach to essential knowledge, the Athenaeum invited ten community partners, including the Chinese Historical Society of New England, the Institute for Human Centered Design, the Museum of African American History, and the North Bennet Street School, to supply their own “required reading” lists. The many absences in Bray’s original picks have been noted, and in some cases, responded to. For example, Bray excluded works by women, but one original volume that fell into private hands has been returned for the exhibition—it bears the signature of its eighteenth-century female owner and that of her daughter.

Required Reading, on view through March 14, 2020, aims to immerse the viewer in the context of the collection and cultivate “a sense of wonder evoked by handmade objects,” said Buchtel. The true showpiece of the exhibition is the replica of the original 1883 bookcase, created by Milwaukee, Wisconsin–based woodworker and exhibition designer Brent Budsberg. Placed in the center of the room, the case has been split in two right down to the portraits of William and Mary. The visitor is invited to step inside the bookcase where they will encounter the community partners’ must-reads and find pencils and slips of paper so that they can submit their own. The hope, Buchtel explained, is that “the ark may be both literally and symbolically opened,” and that our approach to what is essential is similarly expansive.