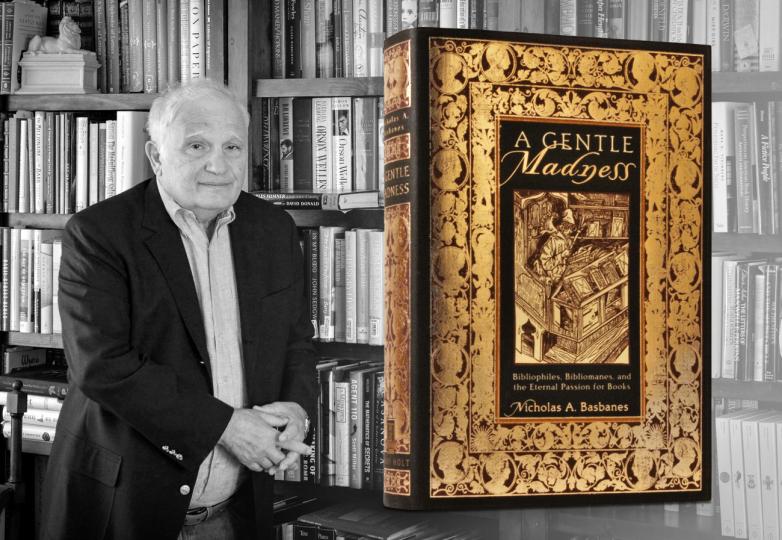

As a non-fiction writer, I pride myself in having earned my stripes as an investigative reporter who develops sources, follows paper trails, and insists on documenting everything. I want to see things in situ, too, and I want to talk to my primary subjects face to face. For A Gentle Madness, that also meant handling the goods—be it a Gutenberg Bible, First Folio, Bay Psalm Book, Poe’s Tamerlane, or an Audubon Birds of America elephant folio. My research archive in the Cushing Library at Texas A&M University includes some 250 hours of taped material for A Gentle Madness alone, all of it converted to digital format and now open to scholars. I have many favorites among them, one a lengthy discourse I had with Charles L. Blockson, a one-time Penn State football star who in 1956 had eschewed an opportunity to play for the New York Giants to become, as he put it to me, “a black bibliophile,” consumed since childhood with documenting his heritage and his history. When we got together in Philadelphia, he had already turned over a massive library of Afro-American material to Temple University, which established a research center in his name that now numbers 500,000 items. He was perfect for my book in many ways, and continues to be a good friend. “How did you learn about me, Nick,” he had asked, when we were wrapping up our first discussion. “I always knew you were out here somewhere, Charles,” I replied. “It was just a matter of time before I found you.”

On April 14, 1991, the New York Times published a lengthy essay I had written under the headline, “Bibliophilia: Still No Cure in Sight.” The piece was a monster, 4,300 words jumping off page one of the Sunday Book Review section, and continuing on four pages inside. With a circulation in those pre-internet days of close to two million copies, this was a very big deal, and the character of what I had been up to for the previous three years changed in a heartbeat. Doors that I once thought were impenetrable were suddenly opened, including a few others that I did not even know then existed.

Two months earlier, I had attended the trial in Des Moines, Iowa, of the notorious book thief Stephen Blumberg. Only a few people knew that I had spent a full day with the reclusive biblio-kleptomaniac one Saturday when court was in recess, had even driven with him to Ottumwa, where the 21,000 books he had stolen from libraries across North America and valued at upwards of $20 million had been kept in an old Victorian house. We had a seven-hour interview that day, something no other journalist had been able to arrange, and I snapped a hundred photographs while I was at it. I had planned on using that material exclusively in my book, but it was such a stunning coup that I made it a central component of my pitch to the Times book review editor.