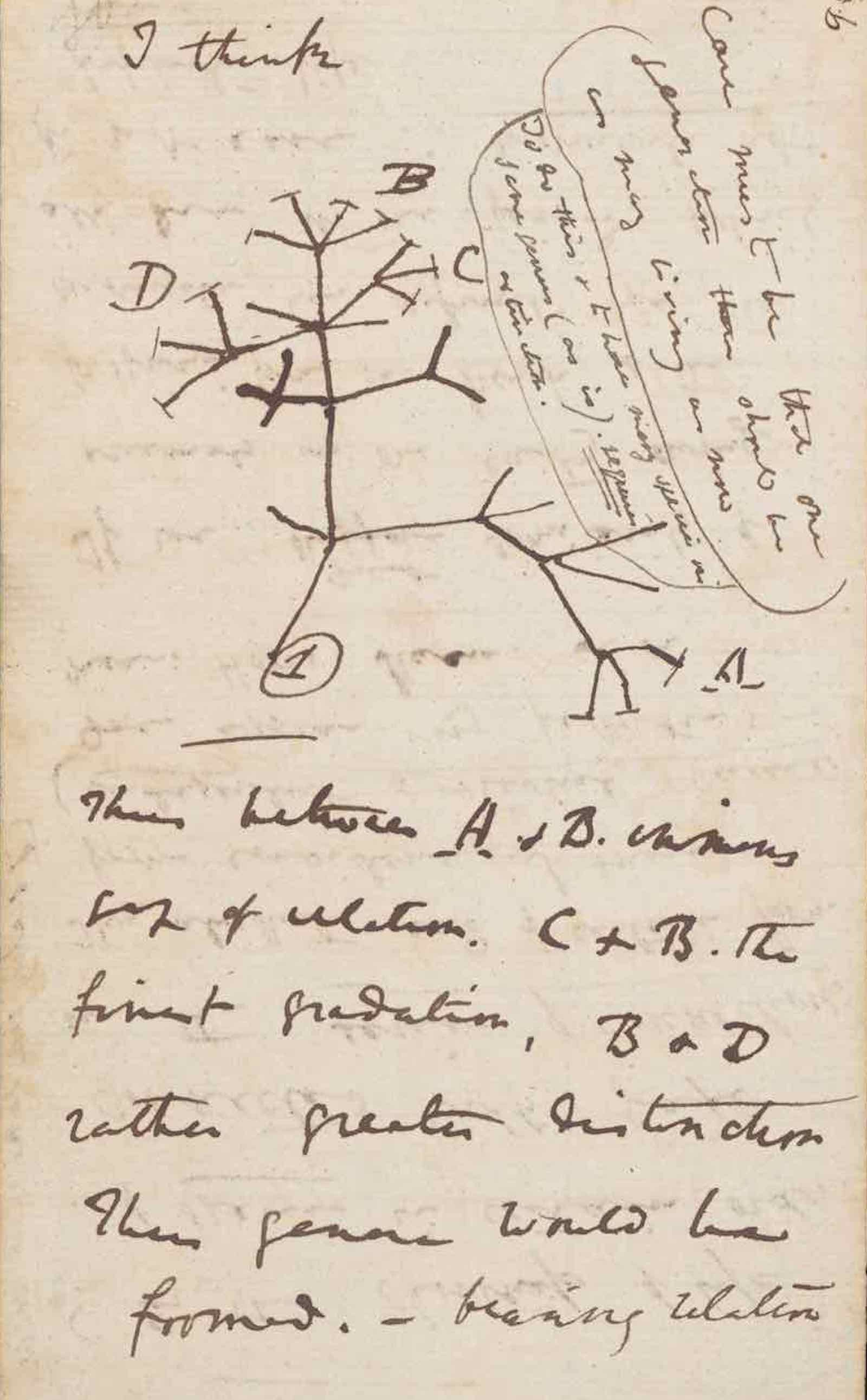

"Darwin’s discoveries demonstrate how dogged and persistent research can produce discoveries that change the world and the value of collaborating with people of diverse backgrounds and experiences. We hope this exhibition inspires generations to explore and push the boundaries of science,” said Elizabeth Denlinger, co-curator of this exhibition along with Dr. Alison M. Pearn of the Darwin Correspondence Project.

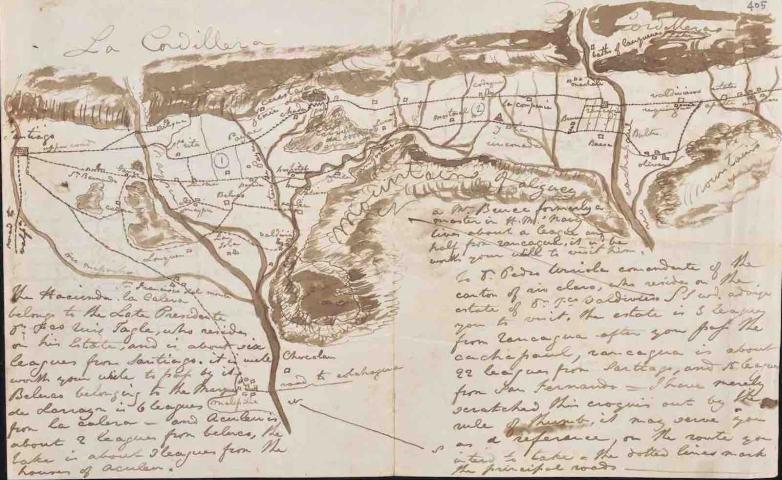

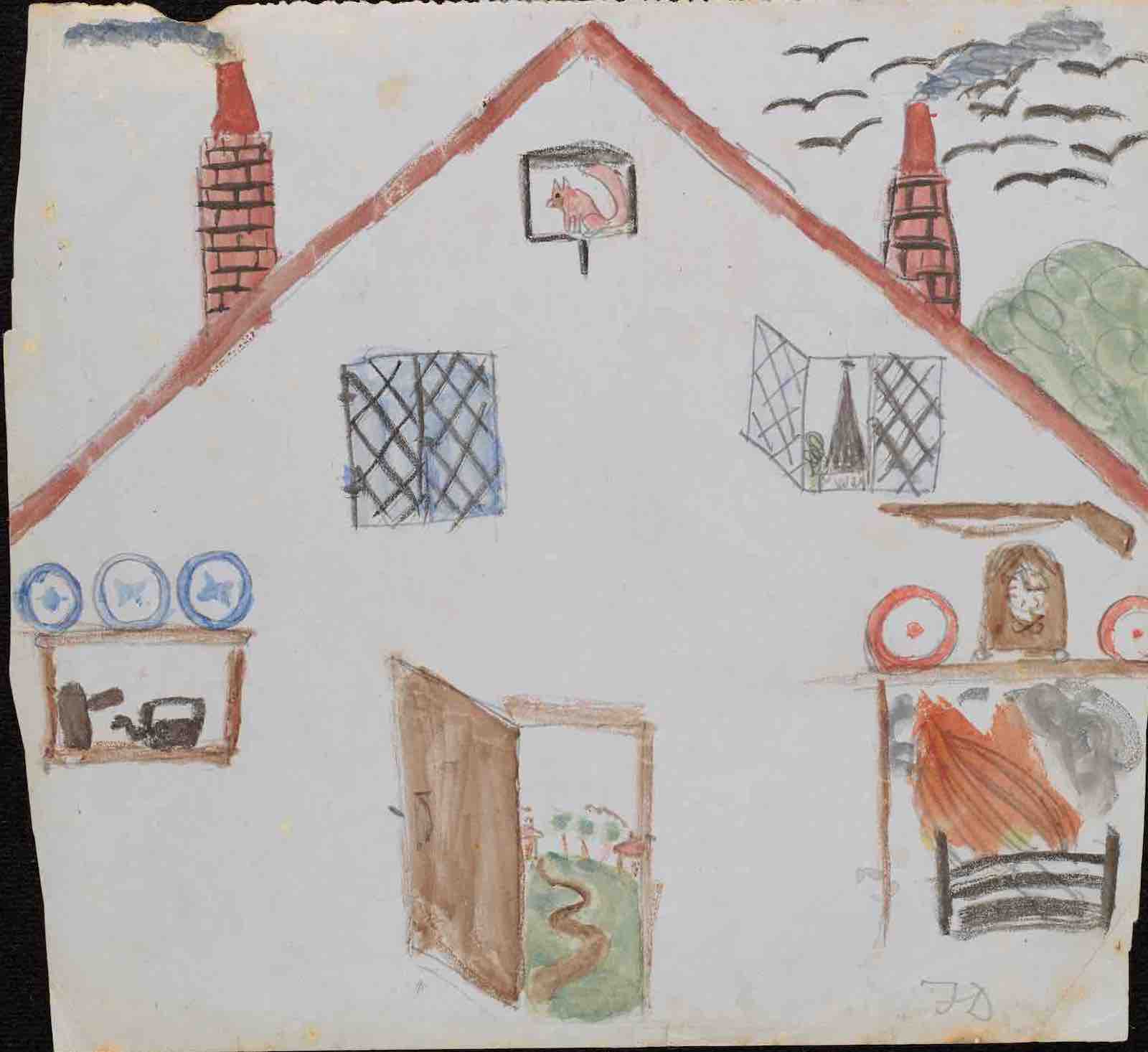

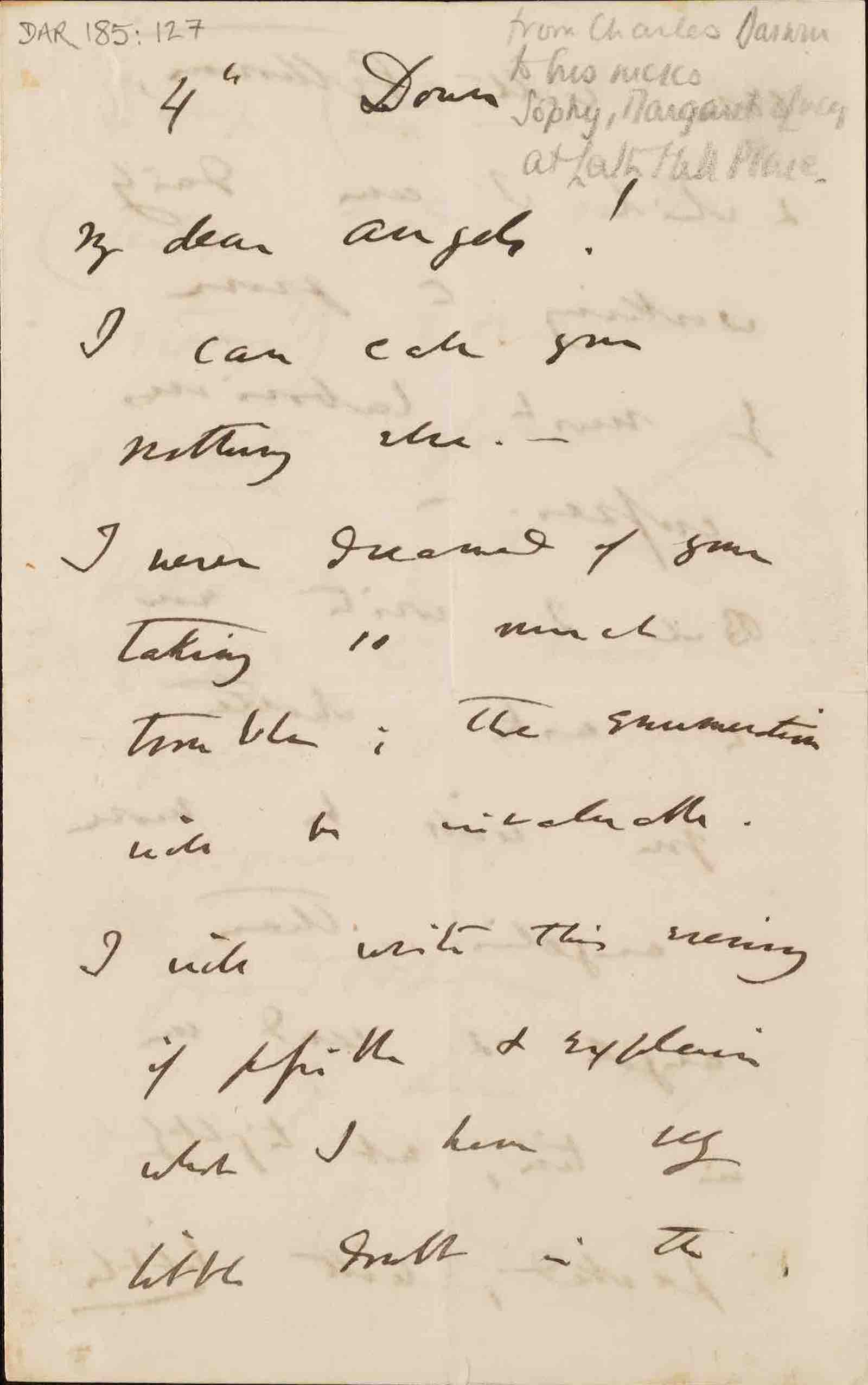

The Library has also curated Charles Darwin: Off the Page, a complementary collection of portraits, maps, and illustrations. The installations, located on the third floor galleries, show both the larger world of Darwin’s work and the intimate spaces of his home, Down House, shared with Emma Darwin and their seven children.

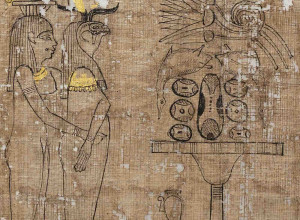

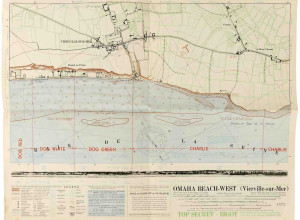

In the Print Gallery, environmental graphics of Darwin's personal world line the walls, flanked by maps showing the global reach of his correspondence both in general and in particular for his late work, The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872). The Library’s collection of photographs of those expressions by the French physiologist G.B. Duchenne de Boulogne will be on view, alongside contemporary illustrations by Mark Pernice of the twining and insectivorous plants which Darwin researched in his last years.