Are You Building An Accidental Book Collection?

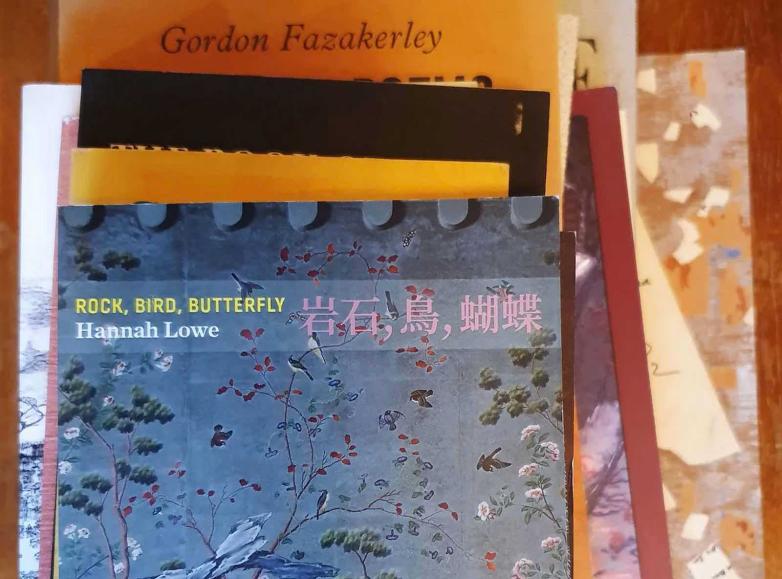

Part of Michael Caines' book collection. Or is it?

This is a guest post by TLS editor Michael Caines, on an accidental collection and not knowing what you're really up to.

How many of them are there? Maybe only two dozen books. Or thereabouts. And where are they? Well, tellingly, they’re scattered across different shelves because, at first, I didn’t see that they might belong together. But pictured above are most of them at least.

These aren’t illustrated books in the sense of featuring visual images created in response to written words. It’s the other way round with this lot – the written words in these books illustrate the visual images – or at least there’s a more equal, conversational partnership at play. They make up what could be called an “ekphrastic” collection; not that this term perfectly covers what all of them are up to, but it’ll serve as shorthand, for now.

Apart from anything else, I’m not wholly sure that I’m “collecting” such books. I like the idea of them as a pleasant, accidental subplot, though, rather than the main collecting narrative here. A couple were review copies; one was a gift at the Small Publishers Fair; at a zine fair in Brixton, I think Tamar Yoseloff of Hercules Editions easily persuaded me to buy, along with a couple of identically small, smart volumes, Hannah Lowe’s Rock, Bird, Butterfly (2022).

From a charity shop, meanwhile, around the same time, I picked up a very cheap copy of the similarly pocket-sized Cuts by Robert Shure (Edinburgh: Canongate, 1974), a little sequence of poems based on 15th and 16th century woodcuts (cf. the recent Emblem by Lucy Mercer).

Some of the other books in the pile feel like exhibitions in print. They include, for example, Paul Durcan’s Give Me Your Hand: Poems inspired by paintings in the National Gallery, London (London: Macmillan/National Gallery, 1994). Durcan had already produced Crazy about Women, inspired by the National Gallery of Ireland, when he embarked on this poet’s stroll among some of the world’s most celebrated works of art. As with Shure, but on a grander scale, most of the resulting poems ventriloquize the sitters in these paintings, often in some cunningly, characteristically askew fashion. Hence Durcan’s Rokeby Venus (ie, The Toilet of Venus by Velázquez): “I lie on my bed / In the raw watching videos”. Hence a portrait of Cardinal Richelieu, subverting the supremely sumptuous portrait of l'Éminence rouge by Philippe de Champaigne.

After Durcan comes a glossy, stiff-backed anthology, Words for Images: A gallery of poems (New Haven. CT: Yale University Art Gallery, 2001), edited by John Hollander and Joanna Weber. Yale University hereby flaunts the magnificence of both its intellectual and material resources: Words for Images captures the “direct literary response” of “twenty-two Yale-trained poets” to “selected twentieth-century artworks residing in the Yale Art Gallery’s collections”. Lowe begins the poem above with the curatorial summary; Shure gives impudent voice to a woodcut; Durcan does likewise with a cardinal. Elizabeth Alexander approaches an oil painting of 1961 by Agnes Martin with a verse exegesis, before moving on.

Ekphrasis is a long-established and still widely practised poet’s game (see the Ekphrastic Review, for example, which exists primarily online, publishing some good work that will presumably never see print).

But there are more ways than one to play that game. I don’t know if these scattered volumes do constitute some kind of interesting collection when they’re put side by side. But the range of approaches, perhaps counterintuitively, suggest to my mind that they do – that is, they offer usefully contrasting views of how poets respond to images, by way of tribute, commentary, critique, dramatization etc.

I’d also be interested to learn whether anybody reading this has likewise found themselves accidentally building up a collection – finding that the nucleus of a potential project, a distraction, a mission, whatever it seems to be, happens to be right there on your shelves already. Traditionally, it seems, book-collecting is framed in terms of intention. For example: “I wish to have a copy of every book ever printed”, as the notorious Sir Thomas Phillipps might have put it. (But then some of the possible sources of motivation I mentioned not so long ago could be troublesomely subconscious ones.) In this case, I concede that this modest grouping of “ekphrastic” volumes of verse grew out of a general interest in poetry and a weakness for pretty pictures. (Not that all of the pictures are pretty.) True bibliomania has more serious symptoms, I’m sure...

Michael Caines is an editor at The Times Literary Supplement, co-editor at the Brixton Review of Books and on the editorial board of The Book Collector. This article first appeared at his substack newsletter Bibliomania.