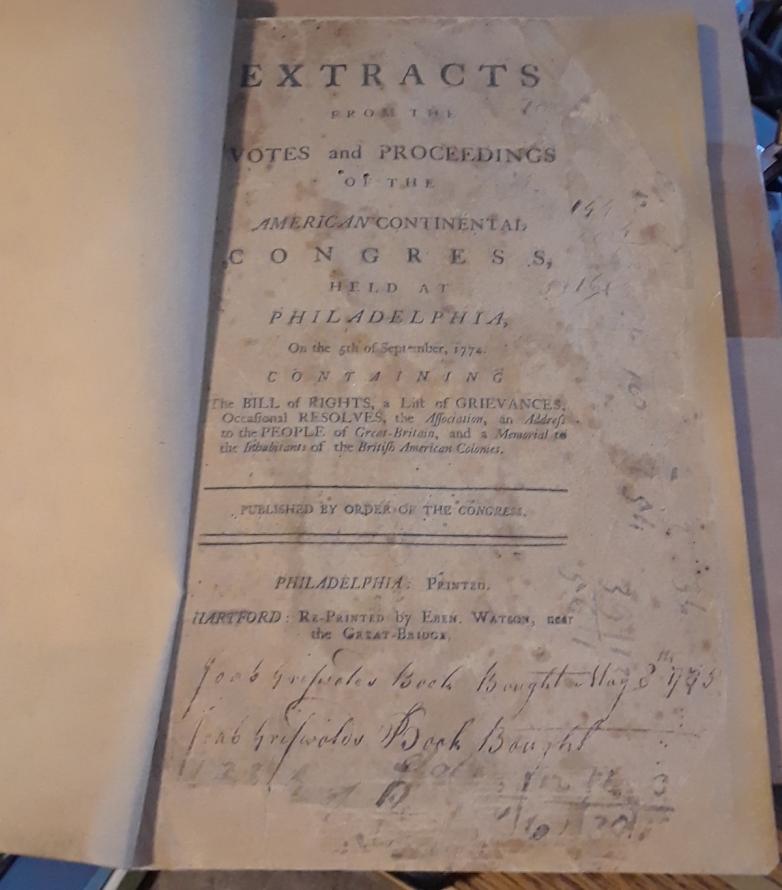

I contacted the American Antiquarian Society in Worcester, Massachusetts, which holds copies of Extracts in their collection, including two Hartford printings by Eben Watson. They confirmed it as a genuine first printing, though it was missing its original wrapper. At 48 pages, it was otherwise complete. The museum advised me not to re-bind. In its current state, it’s closer to an “as issued” condition, they explained, which would make it more attractive to collectors.

I was concerned that this copy of Extracts had been somehow sold by accident. A call to the bookstore owner revealed that he had purchased the four 'atlases' as one package and that they had sat on his shelf for months. He couldn’t recall where he had bought them, and he said that he hadn’t bothered to look beyond the first atlas because that was “not the kind of thing I usually carry.”

How did it come to be wrapped up with three raggedy school atlases? Research in genealogical databases suggests that the students whose names are in the atlases were probably related to Joab Griswater, the original purchaser of this copy of Extracts. Perhaps the four documents traveled together for decades or centuries without being properly examined.

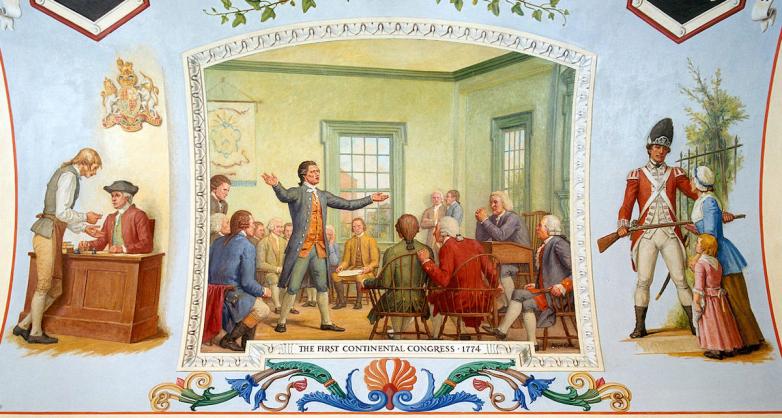

Most Americans have heard of the Second Continental Congress in 1776, which produced the Declaration of Independence. The First Continental Congress is not as well known. A divisive group of colonists had gathered in Philadelphia to marshal a response to the blockade that followed the Boston Tea Party. Many delegates favored conciliation and patience. More radical colonists, such as Samuel Adams, John Adams, and Patrick Henry, urged the Congress away from conciliation and towards revolution. All of them pressed for a definitive statement of the rights of the colonists, which they argued were being ignored by the British crown.

In seven weeks, the 56 delegates from twelve colonies laid the groundwork for both the American Revolution and for the independent nation that would follow. Georgia did not attend, fearing to alienate the British, from whom they were seeking help in their war with Native Americans.

Following adjournment of the Congress on October 26, 1774, William & Thomas Bradford of Philadelphia, printed 120 copies of the Extracts from the Votes and Proceedings of the American Continental Congress. Reprints quickly followed in Albany, Annapolis, Boston, Lancaster, New York, Newport, Norwich, Providence, Hartford, and later in London.

The Extracts included a “Declaration and Resolves” that incorporated an early form of the Bill of Rights, which reflected a radical concept – that some rights had been granted to all men by God himself. The Extracts also included an agreement of the colonies to unite in boycotting imports from Britain and a request for aid from colonists in Quebec. The first copies of the Extracts arrived in London about 20 days after the Congress adjourned.

We might call the Extracts a “booklet.” In colonial America, most printings were “bound” only in the most liberal sense of the word. Two holes were punched with an awl, and string was threaded through the holes to keep the pages together. This was a common binding method in that era, known as “stab-sewn.” What we think of as books were usually custom-made. Readers who wanted a bound book would deliver pages to their favorite bookbinder and select their own binding.

Most surviving Extracts have been bound and rebound multiple times in the past two centuries. To produce a more attractive finished product, bookbinders would often trim the pages to remove tattered edges. As a result, surviving examples of colonial-era printings of the Extracts are of different sizes, often substantially smaller than when first printed. Colonial-era documents were frequently printed on several types of paper stock, due to the vagaries of supply. A 50-page document might sit unfinished for weeks or months due to a lack of paper stock. Most surviving copies are held in museums. Fewer are held by private collectors. Original colonial printings are valued today at $3,000 to $5,000. Colonial issues are more expensive than London printings because the print runs were smaller.

I had my Extracts gently restored for $400 by the Green Dragon Bindery in Shrewsbury, Massachusetts. Stains were removed, tears were repaired, and dog-eared pages were flattened. Caution was taken to ensure that the provenance, in the form of the original owner’s writing, was preserved. As restored, this printing is very close in condition to the way it might have appeared a year after original purchase.

For now, the Extracts has found a place of honor in my collection, although it is such an important document that it seems a shame to keep it for myself. Perhaps one day it will find its way to an institution where it can be enjoyed by others.