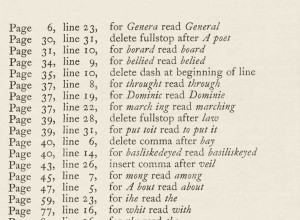

The bookmark as a designed object has a history long entwined with bookbinding when it was usually a ribbon or bit of thread attached to the spine or endband, or even a paper tab inserted into a slit in the page itself. Some of the early bookmarks did more than mark a page, such as the rotating bookmarks of medieval Europe that involved small paper discs that could be oriented to remind the reader of an exact column and line.

In the nineteenth century, with the rise of mass production, the bookmark became popular as its own object. In the 1974 Collecting Bookmarkers, considered to be among the most comprehensive bookmark histories, A. W. Coysh writes that the “first detached and therefore collectable bookmarkers began to appear in the 1850s,” but that it “was not until the 1880s that paper bookmarks became common.” He used his own collection of mostly British bookmarks to trace a chronology of this material change, from embroidered ribbons and wooden paper knives in the Victorian age, for when books still came with uncut pages, to celluloid that imitated tortoise shell and elaborate copper pieces from the Art Nouveau era.

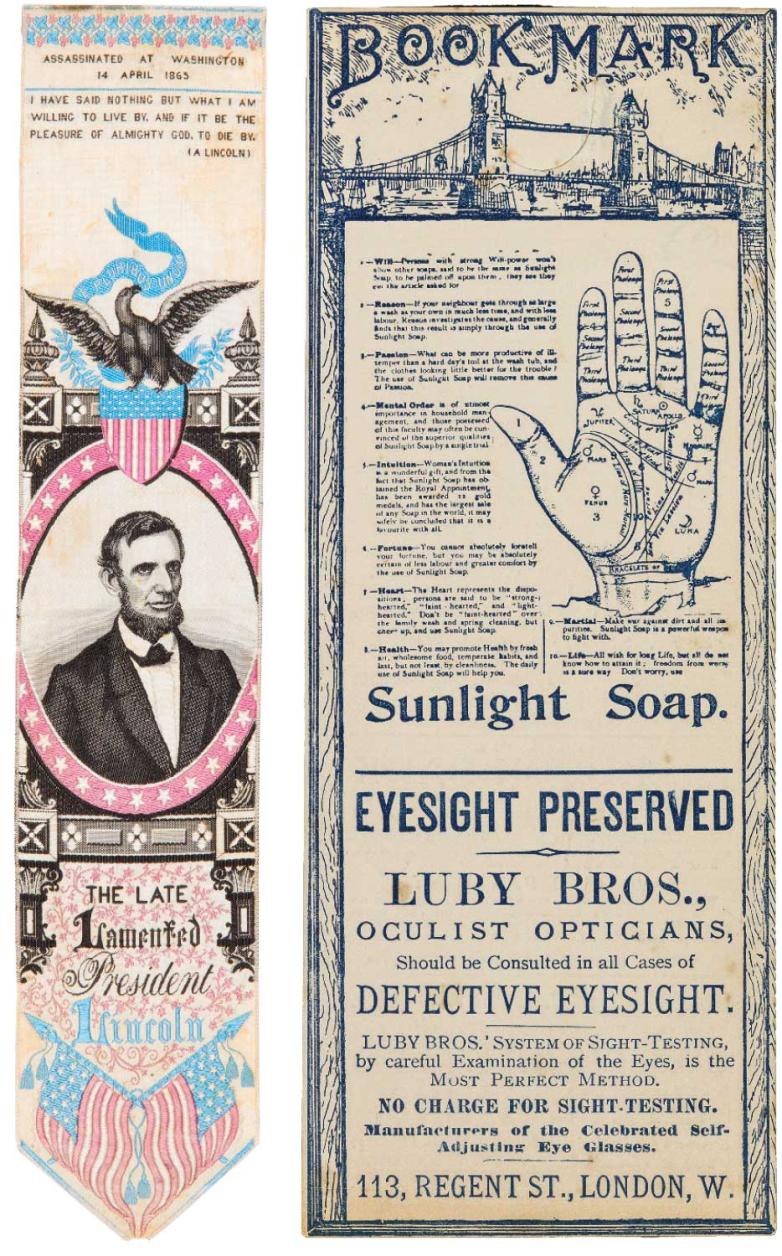

One of the leading bookmark manufacturers of the 19th century was English weaver Thomas Stevens. Customizing the jacquard loom, he created machine-woven silk bookmarks with vibrant scenes for every occasion, whether Christmas greetings or a commemoration of a major event like the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. These “Stevengraphs” remain prized today (there is a dedicated Stevengraph Collectors Association).

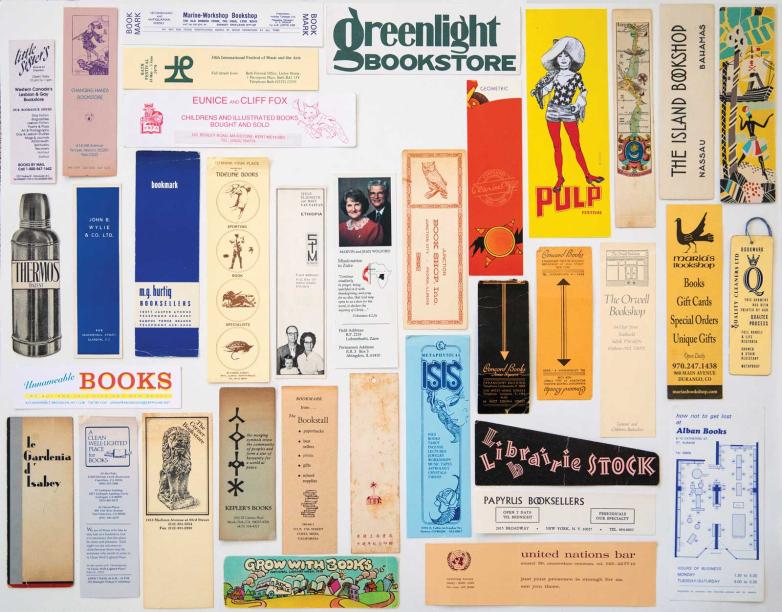

The affordability of printing and distributing paper bookmarks would finally make them ubiquitous as an advertising device, not just for book-related industries but for promoting patent medicines, insurance, soap, cigarettes, and countless other products, making them rich areas of collecting. “They were not only souvenirs in gift shops; they were used as a tool for promotion and public messaging,” said Katie Rudolph, an archivist and librarian at the Denver Public Library, which holds the Ina Zager Bookmark Collection with bookmarks ranging from vacation souvenirs to those warning of playing by power lines.