To mark the bicentenary of Austen’s death, Chawton House Library explored the waxing and waning of literary reputations, reintroducing women writers now unknown outside academic circles. In addition to lectures, concerts, and book launches, two exhibitions premiered this year, both of which consider “lost” literary celebrities: Austen’s predecessor, Eliza Haywood, and her contemporary, Germaine de Staël. Both women received far more recognition in their own lifetimes than did Austen, who was a relatively unknown, moderately successful provincial novelist.

The first exhibition, Naming, Shaming, Reclaiming: The “Incomparable” Eliza Haywood (which I curated), ran from March 20 to June 4. Eliza Haywood (1693–1756) enjoyed a thirty-seven-year publishing career. During this time, she was extraordinarily prolific, publishing at least forty-three works, but perhaps as many as seventy-two. She started off as an actress, and an interest in inventing and reinventing the self is something that informs much of her work. She made her literary debut in 1719 with a three-volume novel called Love in Excess. During the 1720s, she wrote popular seduction fiction, penned gushy manuscript poems to her friends, and published scandal novels, which made barely masked references to her real-life enemies. She was praised by some for her ability to depict with accuracy the pleasures and pains of passion, but she also became infamous as a writer of improper literature that gloried in ruining reputations, and that, because of its semi-erotic content, was dangerous for impressionable young readers.

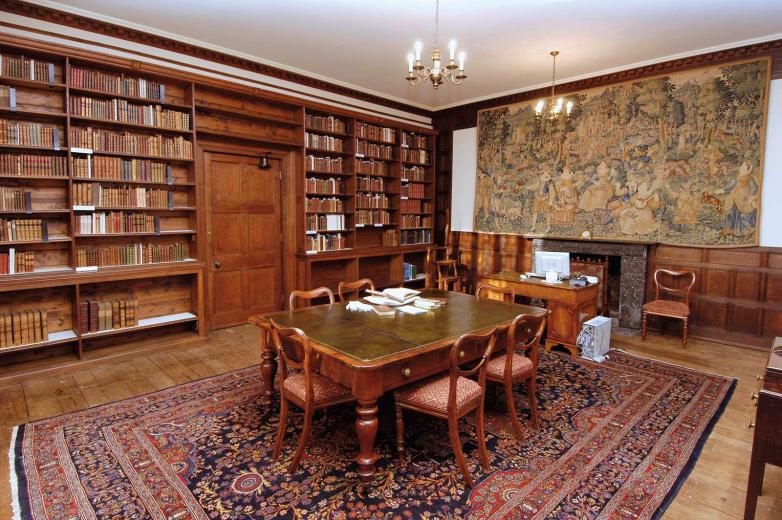

However, despite her portrayal as a trashy romance writer, there are other sides to Haywood, who was a remarkably versatile writer. She was aware of how to use her name, and how to adapt her writing to suit the changing tastes of the literary marketplace. In addition to writing novels like the very popular History of Miss Betsy Thoughtless (1751), Haywood worked as a translator, playwright, satirist, and periodical writer. She ran a pamphlet shop in Covent Garden, and produced political pamphlets, as well as advice manuals similar to modern self-help guides for servants, young women, wives, and husbands. Using rare editions of Haywood’s work from the Chawton House Library collection, the exhibition introduced Haywood in her many guises, created by others and by herself, and reflected on the battles over self-image and reputation that many women writers fought.

The second exhibition, Fickle Fortunes: Jane Austen and Germaine de Staël (curated by Chawton House Library’s executive director, Dr. Gillian Dow), runs through September 24. Austen died in July 1817, but that month also saw the death of Madame de Staël, a superstar of pan-European intellectual, political, and literary life. Born into a Swiss family who lived in France, Staël penned her first play at just twelve years old. She became known later in life for her writings on the philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, on the trial of Marie Antoinette, and on French Revolutionary politics. She hosted salons where the leading intellectuals and politicians met, and published two novels, Delphine (1802) and Corinne, or Italy (1807), the latter of which Austen definitely read, as well as a philosophical work about Germany, De l’Allemagne (1813). Napoleon had this last work pulped during printing because of its sympathetic view of Germany, and this delayed its publication for three years. It was one of many such acts in a long-standing public feud between the two figures. The exhibition aims to put Staël back on the intellectual map, whilst also considering Austen’s extraordinary popularity, and showing how, in the two centuries since 1817, the reputations of these two women writers have realigned in ways that would have astonished their contemporaries.

Whilst 2017 is the year in which we celebrate Austen’s life and works, we also hope to open up exciting new worlds of literature written by other remarkable women during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries for those hungry for more.