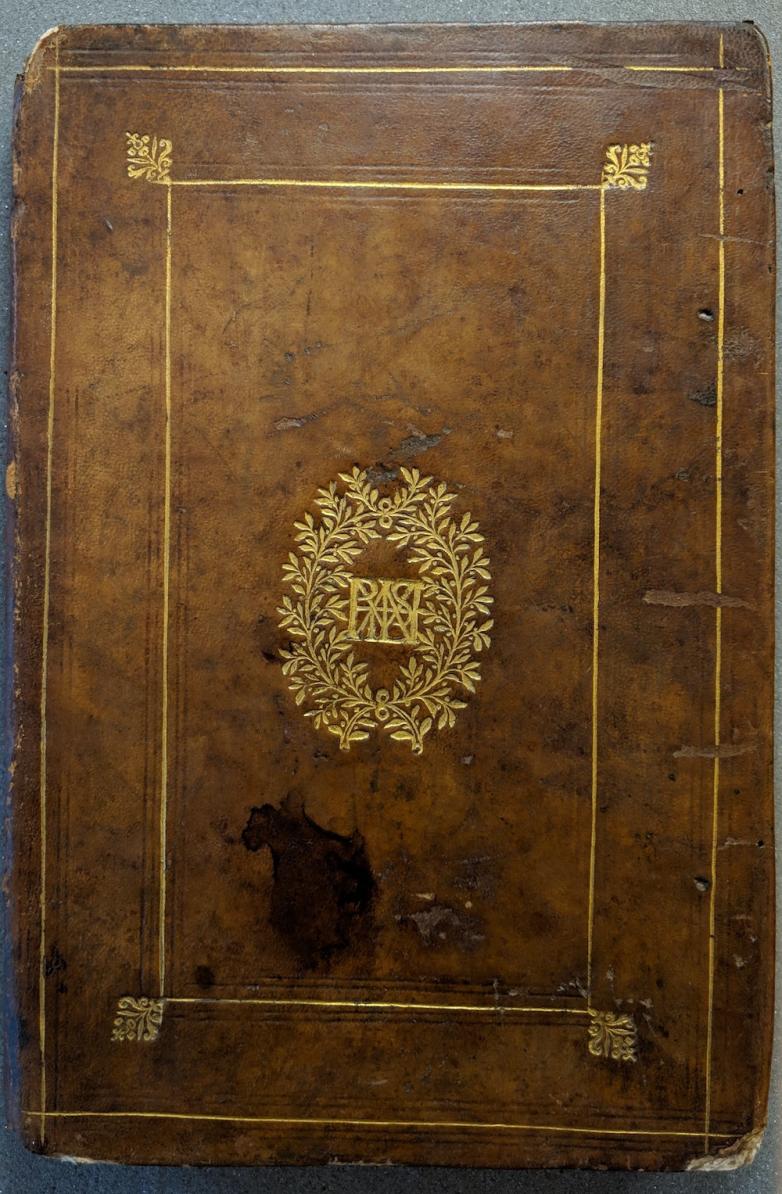

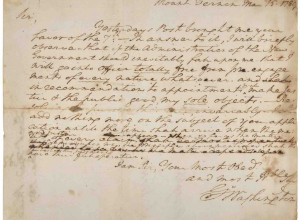

When Braganza, a PhD candidate in Renaissance Literature at Harvard University, told Houghton Library curator John Overholt about her discovery, the book was purchased and brought back to the states, where Braganza has been able to study her book fair find. Close examination of the anagrammatic monogram and early modern bookbinding ornamentation revealed only part of the story, so Braganza turned to biographical information about Wroth and her fiction, specifically the prose romance called The Countess of Montgomery’s Urania, for further clues. Braganza's findings are the subject of a scholarly essay just published in the winter 2022 issue of English Literary Renaissance. What she ultimately determined was that the book was given as a gift by Wroth to her son, with the coded monogram acting as a kind of family tree to clarify (and legitimize) the identity of the boy’s father, William Herbert, 3rd Earl of Pembroke.

“One of the attractions of studying how Wroth braided her life and fictions together is that the pattern she wove is deeply intuitive. There is a real compulsion to understand the evolving and very human relationship between the two,” Braganza said via email. “This opens a space for theories like mine, a freedom to anticipate what her next move might have been and a sense of the fitness of those hypotheses.” So far, the response from scholars in the field to her theory about the Cyropaedia and its cryptic monogram has been supportive.

Through March 11, the Cyropaedia is on view at the Houghton Library in 500 Years of Women Authors, Authorizing Themselves, an exhibition co-curated by Braganza. Her serendipitous discovery will be part of a larger book project on early modern ciphers in art, jewelry, literature, and architecture titled The Secret-Seekers: Renaissance Writers and the Birth of Code, so expect to hear more about Braganza’s fascinating work in the future.