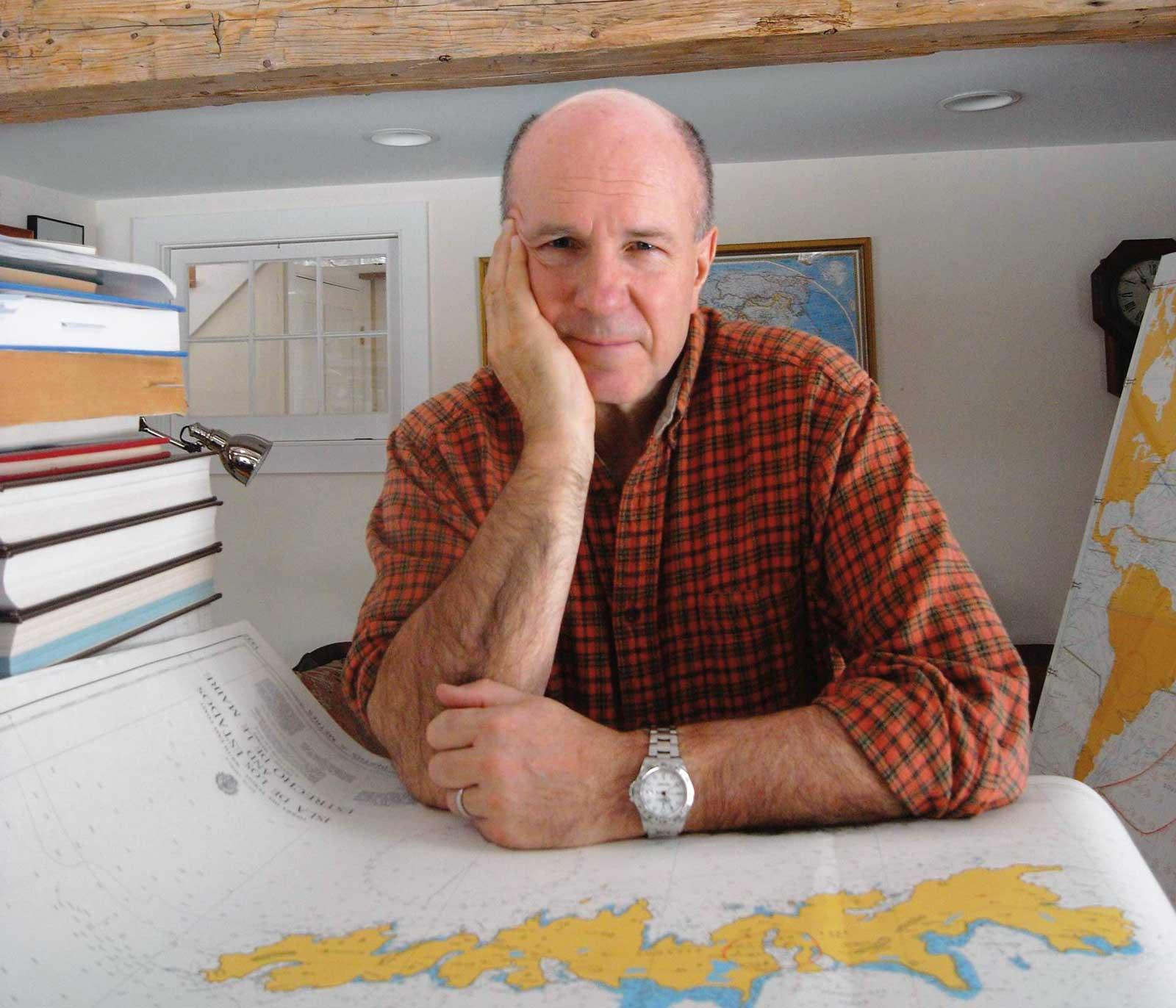

By way of explaining his acquisitiveness, Winchester clarified his writing process. After an initial idea for a book forms, he develops a structure for it, and once that is in place, he starts building a book collection of material related to the various themes.

“With The Men Who United the States, I decided the structure should be a bit more high-risk, so it would be the five classical elements of Chinese philosophies: wood, water, earth, fire, and metal. Once the structures are in place, I know what I want to research. So let us say metal—talking about America—the subjects that I wanted to cover on metal would be the telegraph, the telephone, the distribution of electricity, the television, the radio, and the Internet. I will then get whatever books I can lay my hands on that seem relevant to these discrete subjects. Many of the books are new but most of them are not. I never really purchase anything for my working library other than reading copies of books.”

Winchester estimated he has about 3,000–4,000 books in his working library and 1,000 books in his reading library. But it’s only recently that he has been able to maintain such a large book collection. For many years, Winchester traveled the world as a foreign correspondent, and before that as a geologist. In fact, the Oxford graduate’s first job landed him in west Uganda, where he was searching for copper.

“What I was particularly interested in back then was mountain climbing. I was something of an amateur climber, so I tended to read adventure stories about mountain climbing,” he recalled. “And one of the books I got from this little British Consul library in Fort Portal was a first edition of a book called Coronation Everest by James Morris, which was his account of being the London Times correspondent on the Mount Everest expedition in May 1953.”

Winchester wrote a letter to the author (now Jan Morris) asking for tips on becoming a writer. Winchester received a “tremendously nice” letter in response, which read in part, “My advice to you is quite simple, the day you receive this letter, not next week, not next month but the day you receive it, go into your offices there in Uganda, resign, come back to England, get a job on a local newspaper and write to me again.”