Doyle NY to Auction Important Frida Kahlo Archive on April 15

On April 15, 2015 at 10am, Doyle New York will

hold an auction of Rare Books, Maps & Autographs. Highlighting the

sale is an important archive of 25 love letters written by Mexican

artist Frida Kahlo to Jose Bartoli, a Spanish émigré artist whom she met

in New York. These unpublished letters, comprising more than 100 pages

in Spanish, were cherished by Bartoli along with other keepsakes until

his death in 1995, and have descended in the family to the current

owner. Acclaimed Frida Kahlo biographer Hayden Herrera has written an essay profiling these letters and their significance.

On April 15, 2015 at 10am, Doyle New York will

hold an auction of Rare Books, Maps & Autographs. Highlighting the

sale is an important archive of 25 love letters written by Mexican

artist Frida Kahlo to Jose Bartoli, a Spanish émigré artist whom she met

in New York. These unpublished letters, comprising more than 100 pages

in Spanish, were cherished by Bartoli along with other keepsakes until

his death in 1995, and have descended in the family to the current

owner. Acclaimed Frida Kahlo biographer Hayden Herrera has written an essay profiling these letters and their significance.ESSAY BY FRIDA KAHLO BIOGRAPHER HAYDEN HERRERA

“My

Bartoli…I don’t know how to write love letters. But I wanted to tell

you that my whole being opened for you. Since I fell in love with you

everything is transformed and is full of beauty…. love is like an aroma,

like a current, like rain. You know, my sky, you rain on me and I,

like the earth, receive you. Mara” -- Frida Kahlo, October 1946

This group of twenty-five letters that the Mexican painter, Frida Kahlo wrote to a Spanish refugee named Jose Bartoli between August 1946, when she had just turned thirty-nine, and November 1949, show that she knew how to write love letters that flow with poetry and passion. Kahlo’s letters are steamy with unbridled sensuality and they are, like Kahlo’s paintings, extraordinarily direct and personal. They cry outwith a heart-breaking loneliness and with the misery of physical pain, for they were written while Kahlo was recuperating at home in Mexico City from a spinal fusion performed in June, 1946 at New York’s Hospital for Special Surgery. This was just one of several surgeries that never really cured her physical problems that stemmed from a 1925 bus accident that left the eighteen-year-old Kahlo a partial cripple.

The agony of her spinal surgeries is expressed in Kahlo’s self-portraits starting with The Broken Column, 1944, in which a weeping Frida is pierced by nails and her body is opened up to reveal a crumbling Ionic column. This and other self-portraits speak not only of her wounded body but also of her acute solitude, her feeling of rage and sorrow at not being able to move easily and having to live so often confined within her home. Likewise her letters to Bartoli talk about feeling shut in, isolated, and immobile. But in both her letters and her self-portraits Kahlo defiant — she challenges us with her fierce gaze and with her determination to overcome misery.

The agony of her spinal surgeries is expressed in Kahlo’s self-portraits starting with The Broken Column, 1944, in which a weeping Frida is pierced by nails and her body is opened up to reveal a crumbling Ionic column. This and other self-portraits speak not only of her wounded body but also of her acute solitude, her feeling of rage and sorrow at not being able to move easily and having to live so often confined within her home. Likewise her letters to Bartoli talk about feeling shut in, isolated, and immobile. But in both her letters and her self-portraits Kahlo defiant — she challenges us with her fierce gaze and with her determination to overcome misery.

Tree of Hope, a double self-portrait painted in September and October, 1946, was, Kahlo said in an October 11 letter to her chief patron, Eduardo Morillo Safa who bought it, “nothing but the result of the damned operation.” Eight days later she wrote to Bartoli, who had recently left Mexico, about working on Tree of Hope: “I remembered your last words and I began to paint. I worked all morning and when I finished eating I kept on painting until there was no more light. But afterward I felt so tired and everything hurt.”

In Tree of Hope one Frida lies on a hospital trolley. The surgical incisions on her back are still open and bleeding. The other Frida, dressed in her habitual Tehuana costume, is strong. In one hand she holds the orthopedic corset that in her letters to Bartoli she cursed because wearing it was torture. In her other hand she holds a flag on which she inscribed her motto, the first line of a song that she and Bartoli loved: “Tree of Hope Keep Firm.” Many of Kahlo’s letters to Bartoli mention the tree of hope, and almost every letter reveals her formidable will to keep firm. A photograph of herself that she sent to Bartoli and that she inscribed with the words “tree of hope keep firm,” shows her sitting in the patio of her house in Coyoacan, a southern district of Mexico City. She drew an ink line around the names Mara and Bartoli and she continued this line upward, crossing her chest at the level of her heart and then dividing it so that one line goes down to her right hand and the other goes up to her head.

In Tree of Hope one Frida lies on a hospital trolley. The surgical incisions on her back are still open and bleeding. The other Frida, dressed in her habitual Tehuana costume, is strong. In one hand she holds the orthopedic corset that in her letters to Bartoli she cursed because wearing it was torture. In her other hand she holds a flag on which she inscribed her motto, the first line of a song that she and Bartoli loved: “Tree of Hope Keep Firm.” Many of Kahlo’s letters to Bartoli mention the tree of hope, and almost every letter reveals her formidable will to keep firm. A photograph of herself that she sent to Bartoli and that she inscribed with the words “tree of hope keep firm,” shows her sitting in the patio of her house in Coyoacan, a southern district of Mexico City. She drew an ink line around the names Mara and Bartoli and she continued this line upward, crossing her chest at the level of her heart and then dividing it so that one line goes down to her right hand and the other goes up to her head.

Another 1946 self-portrait that refers to her recent surgery is The Little Deer. Here Frida’s body is transformed into a young stag pierced by arrows. This painting was a gift to her friend Jose Domingo Lavin who had recommended her surgeon, Dr. Philip Wilson and who, her letters reveal, had loaned Kahlo the money to make the trip to New York.

Another 1946 self-portrait that refers to her recent surgery is The Little Deer. Here Frida’s body is transformed into a young stag pierced by arrows. This painting was a gift to her friend Jose Domingo Lavin who had recommended her surgeon, Dr. Philip Wilson and who, her letters reveal, had loaned Kahlo the money to make the trip to New York.

Frida Kahlo met Bartoli, a Catalan artist three years younger than she, when she was lying in bed in the Hospital for Special Surgery. Her younger sister, Cristina, who had come with Kahlo to New York, introduced them. Like Kahlo, Bartoli had experienced great pain. He had fought on the Republican side in the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), after which he was imprisoned in a concentration camp where he secretly drew the horrors that he observed. He escaped and went to Mexico by way of Africa, finally making his home and continuing his political work in New York. During visits to the hospital, he and Kahlo fell in love. When she was released and returned to Mexico, they began an impassioned correspondence.

Kahlo signed her letters “Mara,” which is probably short for “Maravillosa,” which is what Bartoli called her. She told Bartoli to address her in his letters as Sonja so that if her husband, the muralist Diego Rivera found them he would think they were from a woman. A famous philanderer, who in the mid-1930s went so far as to have an affair with Kahlo’s sister, Cristina, Rivera tolerated Kahlo’s love for women, but he was wildly jealous of her liaisons with men. Bartoli sent his letters to the post office where Cristina collected them and took them to her sister. Many of Kahlo’s letters to Bartoli are addressed to Bertram and Ella Wolfe whose Brooklyn home served as a mail drop. Ella was Kahlo’s great friend and confidant; Bertram was Rivera’s biographer.

Kahlo signed her letters “Mara,” which is probably short for “Maravillosa,” which is what Bartoli called her. She told Bartoli to address her in his letters as Sonja so that if her husband, the muralist Diego Rivera found them he would think they were from a woman. A famous philanderer, who in the mid-1930s went so far as to have an affair with Kahlo’s sister, Cristina, Rivera tolerated Kahlo’s love for women, but he was wildly jealous of her liaisons with men. Bartoli sent his letters to the post office where Cristina collected them and took them to her sister. Many of Kahlo’s letters to Bartoli are addressed to Bertram and Ella Wolfe whose Brooklyn home served as a mail drop. Ella was Kahlo’s great friend and confidant; Bertram was Rivera’s biographer.

Although Kahlo was deeply attached to Rivera, these letters suggest that she would have left him in order to live with Bartoli. She told Bartoli that he gave her a kind of love that she had never experienced before. Her love for Bartoli was passionate, carnal, tender, and maternal. She wanted him to know everything about her life, and the letters tell him who she has seen, what she has done, how her health is either improving or worsening, and what doctors have ordered. In many of the letters she talks about her painting, how difficult it is. But she is determined to follow Bartoli’s advice to work hard, to draw, and to be strong. In several letters she tells Bartoli that she is not drawing; once her doctors forbid her to draw or paint. Another time she explained that she had not been able to draw because she was struggling to paint some “son-of-a-bitch rocks that looked like cardboard, but now I have been able to make them look O.K.” In a December 12, 1946 letter she says, “I am working slowly, but with pleasure. I finished a drawing that I owed to Marte R. Gomez, it is not too ugly.” Indeed this pencil self portrait dedicated to her friend, the agricultural engineer, Marte R. Gomez, is perhaps Kahlo’s most beautiful and most finished drawing. In it her joined eyebrows become a dove. (In her letters she calls herself Bartoli’s dove.)

Although Kahlo was deeply attached to Rivera, these letters suggest that she would have left him in order to live with Bartoli. She told Bartoli that he gave her a kind of love that she had never experienced before. Her love for Bartoli was passionate, carnal, tender, and maternal. She wanted him to know everything about her life, and the letters tell him who she has seen, what she has done, how her health is either improving or worsening, and what doctors have ordered. In many of the letters she talks about her painting, how difficult it is. But she is determined to follow Bartoli’s advice to work hard, to draw, and to be strong. In several letters she tells Bartoli that she is not drawing; once her doctors forbid her to draw or paint. Another time she explained that she had not been able to draw because she was struggling to paint some “son-of-a-bitch rocks that looked like cardboard, but now I have been able to make them look O.K.” In a December 12, 1946 letter she says, “I am working slowly, but with pleasure. I finished a drawing that I owed to Marte R. Gomez, it is not too ugly.” Indeed this pencil self portrait dedicated to her friend, the agricultural engineer, Marte R. Gomez, is perhaps Kahlo’s most beautiful and most finished drawing. In it her joined eyebrows become a dove. (In her letters she calls herself Bartoli’s dove.)

Several of the 1946 letters let Bartoli know that she has missed her period. If the condition of her spine would allow it, she was half-hoping to have Bartoli’s baby. “If I were not in the condition I am in now and if it were a reality, nothing in my life would give me more joy. Can you imagine a little Bartoli or a Mara?”

Several of the 1946 letters let Bartoli know that she has missed her period. If the condition of her spine would allow it, she was half-hoping to have Bartoli’s baby. “If I were not in the condition I am in now and if it were a reality, nothing in my life would give me more joy. Can you imagine a little Bartoli or a Mara?”

Reading Kahlo’s letters can make you feel claustrophobic—almost as shut in as she was. Much of her writing is taken up with how lonely she feels without him and how she is suffering. She is vehement about her need for Bartoli. “Don’t leave me, don’t forget me,” she keeps saying. She wants to be him and to have him be her. Quite often she slips into a kind of emotional blackmail—she will get better for him; only he can make her happy; he is the reason she stays alive. He is her tree of hope, the support without which she cannot paint. This neediness might at one point have driven him away. One of two letters that she wrote to Bartoli in 1947 express her anguish when she learned from a friend that he had been in Mexico for three weeks and he had not come to see her. Their relationship had resumed by 1949 and in her letters from that year she is just as desperate for him to be close.

Bartoli never lost his love for Frida. If you asked him about her he would speak with great reverence, but also with restraint. All his life he treasured the little objects she gave him as tokens of her love and he kept all her letters. Kahlo sometimes worries that Bartoli would find her letters to be childish, corny, and stupid. But, she tells him, love letters are never intelligent or stupid. Her letters are her “truth.” She asks him to receive them “as if a little girl passing in the street gave you a flower without knowing why.” -- Hayden Herrera

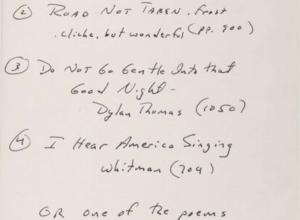

SYNOPSES OF THE LETTERS

Hayden Herrera has written a summary in English of the content of each letter. To download a pdf of the synopses, click here.

Books, Autographs & Maps

For information on books, autographs and maps from other collections and estates to be offered in the April 15 auction, as well as the Rare Book Collection of the New York City Bar Association, click here.

Photographs

For information on photographs from other collections and estates to be offered in the April 15 auction, click here.