The Huntington Purchases Rare Pasteur, Austen Family, and “Wicked Ned” Collections

SAN MARINO, Calif.—The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens added important rare material to its history of science collection recently: handwritten research notes by Louis Pasteur (1822-1895) on the brewing of beer, furthering the scientist’s understanding of the fermentation process; and, for the manuscripts collection more generally—1,000 pages by a sailor and largely self-taught writer and artist who called himself “Wicked Ned,” and a collection of unpublished letters, poems, and other material from the family of Jane Austen.

The Huntington’s Library Collectors’ Council purchased the collections at its annual meeting earlier this month. “These are each spectacular additions to the library,” said David Zeidberg, Avery Director of the Library at The Huntington. “And while Pasteur and Austen may be household names and those materials are compelling in their own right, I have to say, the Wicked Ned material is absolutely stunning.”

The Library Collectors’ Council is a group of 37 families who help support acquisitions. It was formed to augment the collections by helping to purchase materials that the institution otherwise could not afford.

Highlights of the newly purchased materials:

Louis Pasteur’s notes on brewing beer

Pasteur, the French chemist known for his important discoveries that led to vaccines and other major milestones in disease prevention, was a pioneer in the study of fermentation. It was studying fermentation, in fact, that led him to focus on and promote the process that ultimately became known as pasteurization—initially developed to keep wine and beer from souring, and then later used to preserve milk. The eight leaves of Pasteur’s lab notes on beer brewing from the 1870s “demonstrate how he knew that what he was doing with beer would provide conceptual tools for developing vaccines against anthrax and would lead eventually to rabies inoculations,” said Melissa Lo, Huntington curator in the history of science.

The notes—scribbled on various sizes of paper, in black ink and blue and black pencil— also reveal a politically motivated scientist trying to help his country, which recently had been defeated in the Franco-Prussian War. If he could help his countrymen figure out how to brew a better beer, said Lo, he could thus help the French continue to rally against the Prussians. Ultimately, his work in fermentation helped transform the beer industry throughout the rest of the century. Based on his work, his fellow Frenchmen began to heat their concoctions to at least 50 degrees C (122 degrees F) to kill off putrid microbes. By the early decades of the 1880s, German and American brewers followed suit, and “pasteurization’”—this was when the term was coined—started being practiced worldwide. “It just goes to show,” quipped Lo, “that a little bit of beer goes a long way.”

The Huntington has a sizable Pasteur collection, among the best in the country, said Lo. “These notes provide a key window into a particular area in the history of science, but my sense is that these may well be of interest to researchers who more and more are investigating the history of food and drink, as well as hand-crafted beer.”

Wicked Ned

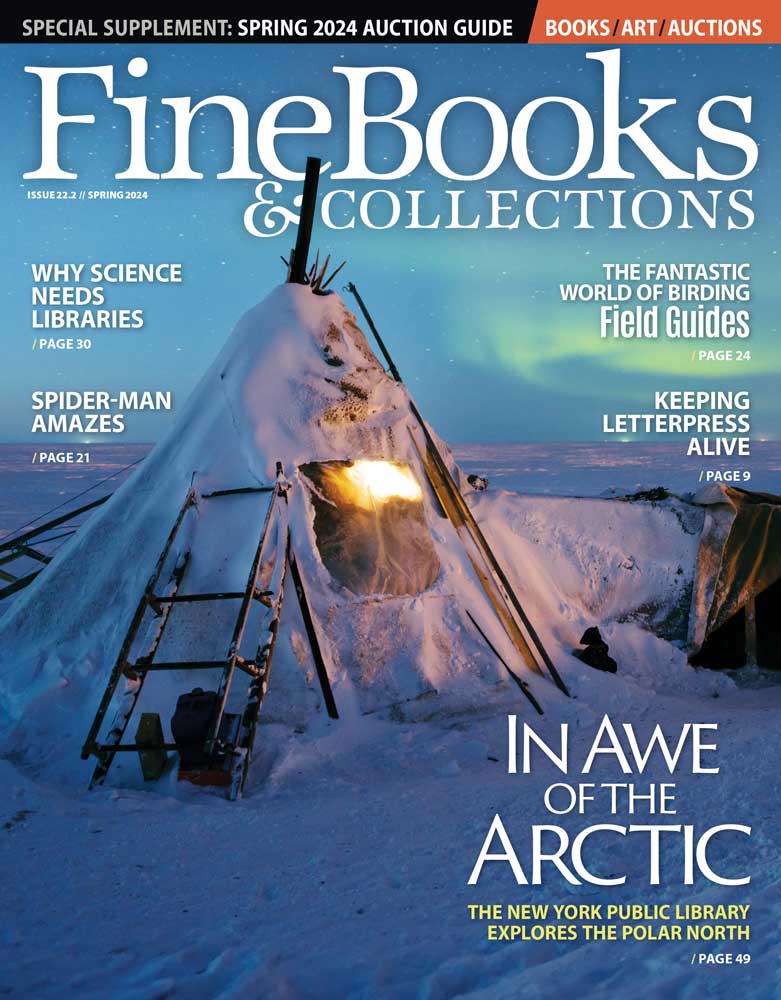

Also purchased was a treasure trove of writings, drawings, and watercolors created by a remarkable 19th-century New England seaman. David E. Marshall, who adopted the pseudonym Wicked Ned, had a colorful maritime career and considerable literary and artistic talent. A son of a Connecticut sea captain, Marshall first went to sea at the age of 13 and remained in the service of “Daddy Neptune” for the rest of his life, serving, he wrote,“on every type of boat, from a clam boat to a 74, and in all capacities, from cook to captain.”

In the 1820s, he sailed on ships “of dubious character,” as he characterized them, and was essentially a pirate. Later on, he worked on the Great Britain, the largest sailing passenger ship of the time, and in the 1840s, he made several trips around the world on whaling ships. In the 1850s, he was employed as the captain’s clerk on board two frigates of the United States Navy, the Raritan and the Savannah. During the Civil War, Marshall served as a naval quartermaster on transport ships of the Union Navy.

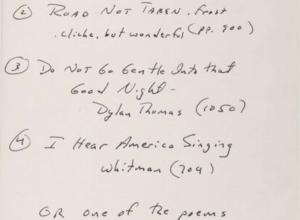

A quintessential autodidact—Marshall was expelled from school when he was 10— “Wicked Ned” was an accomplished writer and extraordinarily gifted artist. In his lavishly illustrated manuscript journals, Marshall documented his adventures, reflected on American political and social ills, recorded his innermost thoughts, and composed poetry, including a long poem depicting his 1846 whaling voyage.

“One of Marshall’s most fascinating journal entries is a rather savage diatribe denouncing Christian missionaries’ efforts to enlighten the ‘savages’ of the Sandwich Islands,” said Olga Tsapina, Norris Foundation Curator of American Historical Manuscripts. “Marshall even switches to red ink, as if to make the paper blush with outrage. Stripped of their native identity, the Sandwich Islanders were robbed of their national pride. Marshall wrote:‘ever since he has become partially civilized and enlightened, the comparison he has been able to draw between his own and other countries has created an unnatural loathing towards his own race, or that memory still clings with regret to the customs and affectations of former days.’”

The poem depicting Marshall’s whaling journey ends with a scene of a burial at sea. The deceased mariner, Marshall writes, was “one, real nature’s son, / A native of New Zealand savage land,” and “each hardy seaman” sighed for him. Marshall continues: “and cheeks were wet which tears have seldom wet,” for “he was generous, noble, and was brave.”

“Wicked Ned’s journals offer a very rare glimpse into the lives of sailors and mariners, generally less given to keeping elaborate journals than their higher-ups,” said Tsapina. “To get these kinds of depictions and his insights—it’s extraordinary.”

The pages of the three large folio volumes are accompanied by some 200 striking watercolors, pencil, and ink drawings depicting Marshall’s exploits, recollecting his adventures, and fondly recalling his New England home. “From a purely documentary standpoint, these are extremely rare and wonderful visual insights into what a sailor’s life was like,” said Tsapina. “But the quality of the drawings are astonishing—remarkable for a self-taught artist.”

Leigh Family Papers (Jane Austen’s Mother was Cassandra Leigh)

The Council also acquired 52 unpublished letters, poems, and other materials from Jane Austen’s mother’s family, the Leighs of Adlestrop. The collection spans six generations, capturing intimate family relationships across time.

“This is a deeply personal collection of family papers that draws back the curtain on the formalities of society in 17th- and 18th-century England,” said Vanessa Wilkie, William A. Moffett Curator of English Historical Manuscripts. “We’re looking at correspondence revealing the intimate, mundane, playful, and tragic aspects of the times.” The collection spans almost 200 years, with a range of voices from within one lineage. “You get a dear mother, affectionate father, dear son, dear cousin, dear brother, dear little niece, dear Madame, and even A. Nonymous,who writes a really funny letter that cautions against the dangers of falling in love with Miss Fortune.”

Historians and literary scholars continue to mine the legacy of Jane Austen, already well studied. These materials provide an unpublished window into her mother’s side of the family. It does not include Jane Austen material; most of her letters were burned by her sister after her death. The collection supplements other Leigh family material already in The Huntington’s possession.

Image: David E. Marshall (“Wicked Ned”), Right Whale, ca. 1851, watercolor. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.