Dan Flavin's Drawings at the Morgan

New York, NY, January 2012—Best known for his groundbreaking fluorescent light installations, Dan Flavin (1933-1996) was also an avid draftsman and collector of drawings. Throughout his career, the self-taught artist turned to drawing to plan his constructions and installations, as well as to sketch from nature in the most traditional fashion. He also enthusiastically acquired drawings by artists of diverse styles and backgrounds with whom he felt affinities.

??

Now, for the first time, the central role that drawing played in Flavin’s art will be explored in a major exhibition at The Morgan Library & Museum, opening on February 17, 2012. The show includes more than one hundred drawings by the artist—from early abstract expressionist watercolors of the 1950s and portraits and landscape sketches, to studies for his seminal light installations and late pastels of sailboats. In addition, the exhibition will feature nearly fifty works from Flavin’s personal collection of drawings, including nineteenth-century American landscapes by Hudson River School artists, Japanese drawings, and twentieth-century works by artists such as Piet Mondrian, Donald Judd, and Sol LeWitt. The exhibition will be on view through July 1, 2012.????

"The world knows Dan Flavin through the iconic fluorescent light installations on which his reputation rests," said William M. Griswold, director of The Morgan Library & Museum. "But few people are aware that these magnificent pieces often began as sketches, schematic drawings, and diagrams on graph paper. Throughout his career, Flavin turned to drawing to explore new ideas and new themes, and collected drawings by old and modern masters to serve as sources of inspiration. The Morgan is delighted to present this first-ever retrospective look at the key role that drawing played in the creative process of one of the twentieth-century’s most innovative artists."????

Early works

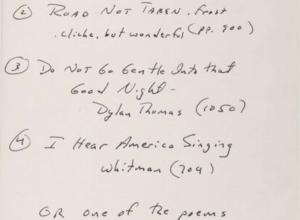

Dan Flavin: Drawing begins with the artist’s early drawings and watercolors. Landscapes are often the subjects of these works, and they reveal his interest in atmospheric and meteorological conditions, stemming from his training as a meteorological technician while in the Air Force. His admiration for Abstract Expressionists such as Willem de Kooning and Franz Kline led him to adopt a broad, gestural style. Particularly important among his works of the late 1950s is a group of watercolors with handwritten texts copied from the Bible, as well as from Irish and Chinese poetry and from James Joyce—a figure with whom the young Flavin identified, owing partly to their shared Irish heritage. ????

Early on Flavin began the practice, which he would continue throughout his career, of dedicating his works not only to friends and relatives, but also to historical figures and people whom he admired, such as Picasso and Cézanne. Some of these lengthy dedications express Flavin’s political and social engagement, as in the 1961 watercolor to those who suffer in the Congo, a reference to the crisis that ensued after the Congo achieved independence in 1960.????

Drawings for icons and related constructions??

Flavin’s first sustained series of constructions with light are the icons, created between 1961 and 1963. Each consists of a painted wooden square to which one or more lamps have been attached. Although only eight were fabricated, drawings document ideas for many more. Their collective title was inspired by the artist’s interest in Russian art of the early twentieth century, notably that of Kasimir Malevich, who referred to his abstract art as "the icon of my time." Likewise, Flavin compared his use of electric light to a modern type of icon. With characteristic irony, however, he noted that his icons "differ from a Byzantine Christ held in majesty; they are dumb—anonymous and inglorious . . . They are constructed concentrations celebrating barren rooms. They bring a limited light."??

The drawings for Flavin’s icons range from small sketches on 3 x 5 inch notebook pages—a favorite support for his working drawings—to large, finished studies in colored pencil or pastel. icon V (Coran Broadway Flesh) is the subject of several detailed drawings, probably because, with the number of lamps it includes, it is one of the most complex in the series, but also no doubt because Flavin considered it to be his best work at the time. It is "a perfectly resolved piece—symmetrical square of one color which is totally lighted," he wrote in his journal. Obsessed with keeping records of his work, Flavin drew several "inventories" of his icons, taking stock of those already made and planning future ones. Many drawings document various possible arrangements of several icons together, attesting that, although they were eventually sold individually, these works were first conceived as a group. ????

Drawings for fluorescent light installations

??From 1963 until the end of his life, the fluorescent light installations for which he is celebrated constituted Flavin’s main artistic production. These were first worked out in rapid sketches on the pages of the 3 x 5 inch notebooks he carried with him at all times. Using a fine ballpoint pen, Flavin combined visual and verbal notations, including such inscriptions as the color and dimensions of the lamps. Sometimes writing and drawing became one as Flavin literally "drew" the fluorescent tubes with the words designating their color. Some studies were on larger sheets, usually of 8 1/2 x 11 inch typing paper, a support that, like the notebook pages, demonstrated a preference for nonartistic paper. Indeed, Flavin did not treat his working sketches as master drawings. "For me, drawing and diagramming are mainly what little it takes to keep a record of thought...," he wrote. But his drawings were essential to his working process, and he carefully kept them. All were precisely dated and sometimes numbered to record the sequence in which they were made. ????

In the 1960s, Flavin also created finished drawings in preparation for his installations, using colored pencil and sometimes colored paper to suggest the interaction of the lights in the space. A few of these exist for the Green Gallery installation of 1964, Flavin’s first exhibition of fluorescent lights. As he became more familiar with the effects of lights, he no longer felt the need for such drawings. The later ones were made primarily for the market.

??

Beginning in 1971, Flavin kept visual records of his installations through what he called "final finished diagrams," carefully drawn in colored pencil on graph paper. These were not drawn by him but by others following his instructions—first his wife Sonja, and later his son, Stephen, and other assistants. The draftsperson’s initials appear on the sheet, next to Flavin’s signature. Delegating the actual making of a work is unusual with drawings, which are traditionally associated with the artist’s hand. But Flavin’s approach was in keeping with developments in Minimal and Conceptual art of the 1960s and 70s, which stressed the role of the artist as the person who conceives the work, though he may not be the one who actually executes it. This was notably the case with Flavin’s light installations. He planned them and closely supervised their placement, but the pieces, commercially available, were installed by electricians. ????

Landscapes, sails, and portrait drawings

??Perhaps the most unexpected aspect of Flavin’s drawing production is the numerous landscape sketches he made outdoors from observation. Particularly drawn to riverbanks and ocean shores, he often sketched views of the Hudson River and Long Island beaches. In these quick drawings, he would capture the mood of a scene in a few strokes. Working in series, he made many sketches from the same point of view in rapid succession. Unlike his studies for light installations, these drawings were made in traditional artists’ sketchbooks and in graphite pencil. Exercising the same care he took with his working studies, Flavin dutifully recorded the date, subject, and location of each sketch, sometimes even the weather conditions of the day on which it was made. For the purpose of exhibitions, he would frame many of them together, in sequences reflecting the order in which they were created.

??

During the 1980s, Flavin focused on the subject of sails in charcoal and pastel drawings whose spare composition and calligraphic qualities reflected his interest in Asian art. First drawn from observation, these were eventually made from imagination, allowing Flavin to draw them in any season. In addition to the landscapes, Flavin frequently drew portraits of his friends or of people he encountered by chance, for instance at restaurants or cafes. Often in ballpoint pen, these drawings can be found interspersed with sketches for light installations in Flavin’s notebooks. Rendered with quick, short marks, these likenesses often border on caricatures as the artist sought to catch his subjects’ salient features. ????

Flavin’s collection??

Highlights from Flavin’s collection include sheets by early-twentieth-century abstract painters such as Arp and Mondrian, both of whom he mentioned several times in his journal during the 1960s. Rather than finished drawings, Flavin sought sketches and studies, in which he found the most direct expression of the artist’s thoughts. Because of his own habit of working out his installations from quick notations on small pieces of paper, he felt a connection with artists like Mondrian, who could plan a painting by jotting down a few lines on the wrapper of a pack of cigarettes. Drawings by Hans Richter and George Grosz from the late 1910s and early 1920s are evidence of Flavin’s interest in the constructivist phase of Dada. ????

Flavin’s collection also includes many drawings—probably acquired through exchange—by his friends and contemporaries. A large sheet by the Chinese-American artist Wallace Ting is a reminder that it was he who introduced Flavin to sumi ink—a medium the latter used extensively in the late 1950s. Drawings by Donald Judd, Robert Morris, and Sol LeWitt evoke Flavin’s friendship with other artists associated with the Minimalist movement. He was particularly close to LeWitt, who has acknowledged the influence of Flavin’s concept of series on his own development, and to Judd. Earning his living as an art critic in the early sixties, Judd wrote several pieces on Flavin, praising "the power and complexity" of his work. Judd’s drawings in Flavin’s collection are related to his early Minimalist sculpture. Two elegant designs in gouache and pastel show that the two men shared the same interest in the use of color to create objects that combined aspects of sculpture and painting while being neither. ????

Flavin developed an interest in nineteenth-century American landscape drawings during the 1960s, especially after he moved to Cold Spring, in the Hudson River Valley, in 1965. His most intense period of acquisition of works by Hudson River School artists was 1979-81, when he bought a large number of them on behalf of Dia Art Foundation for the purpose of displaying them at a planned Dan Flavin Art Institute in Garrison, New York, a project that was never completed.

??

Flavin had a lifelong interest in Asian art as well, the influence of which is visible in his work from his early ink and charcoal drawings to his late pastels of sails. In the mid-1980s Flavin purchased over thirty Japanese drawings from Galerie Janette Ostier in Paris. Most of them date to the first half of the nineteenth century and are by artists associated with ukiyo-e (pictures of the floating world), such as Hiroshige, Hokusai, and Kuniyoshi. Japanese drawing epitomizes the combination of expressivity and economy that Flavin aimed to achieve in his own art.

??

Light installations at the Morgan??

Two major fluorescent light installations by Flavin will also be on view. At the entrance of the exhibition, visitors will encounter Flavin's untitled (to the real Dan Hill) 1a, 1978, a work composed of pink, yellow, green and blue light cast in two directions: out towards the viewer and back into the corner of the gallery. A spectacular corner installation, untitled (in honor of Harold Joachim) 3, 1977, an eight foot square grid, will suffuse the Clare Eddy Thaw Gallery on the ground floor with pink, yellow, green and blue light. Several studies related to this work are on view in the exhibition. ??????

Public Programs

??Family Program

??Glow Play: Sculpting with Light??

Saturday, February 25, 2-4 p.m.??

Artist and educator Nicole Haroutunian will invite children and their families to discover the drawings of Minimalist artist Dan Flavin. After visiting the exhibition and experiencing two of the artist's light installations first hand, they will then create color sketches inspired by Flavin's works on paper and shape glowing sculptures of their own.??

Adults: $6; Members: $4; Children: $2????

Gallery Talk ??

Dan Flavin: Drawing ??Friday, March 2, 7 p.m.??

With Isabelle Dervaux, Acquavella Curator, Modern and Contemporary Drawings??

Free????

Symposium ??Minimalist Drawing: The 1960s and 1970s??

Friday, April 27, 10:30 am-5 p.m.??

This symposium will explore the changing form, function, and status of drawing in the era of Minimalism and Conceptual art. Speakers to be announced. ??$15; $10 for Members; free to students with valid ID.????

Additional programs to be announced

????Organization and Sponsorship

This exhibition is supported in part by the Dedalus Foundation, Inc. and Nancy Schwartz, with additional assistance from The Aaron I. Fleischman Foundation. ??

Major funding for the catalogue is provided by Lannan Foundation. ????Dan Flavin: Drawing is organized by Isabelle Dervaux, Acquavella Curator of Modern and Contemporary Drawings at The Morgan Library & Museum.??

The Morgan exhibition program is supported, in part, by public funds from the New York State Council on the Arts and the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs.

The Morgan Library & Museum??

The Morgan Library & Museum began as the private library of financier Pierpont Morgan, one of the preeminent collectors and cultural benefactors in the United States. Today, more than a century after its founding in 1906, the Morgan serves as a museum, independent research library, musical venue, architectural landmark, and historic site. In October 2010, the Morgan completed the first-ever restoration of its original McKim building, Pierpont Morgan’s private library, and the core of the institution. In tandem with the 2006 expansion project by architect Renzo Piano, the Morgan now provides visitors unprecedented access to its world-renowned collections of drawings, literary and historical manuscripts, musical scores, medieval and Renaissance manuscripts, printed books, and ancient Near Eastern seals and tablets.????

General Information??

The Morgan Library & Museum??

225 Madison Avenue, at 36th Street, New York, NY 10016-3405

??212.685.0008??

www.themorgan.org????

Hours??

Tuesday-Thursday, 10:30 a.m. to 5 p.m.; extended Friday hours, 10:30 a.m. to 9 p.m.; Saturday, 10 a.m. to 6 p.m.; Sunday, 11 a.m. to 6 p.m.; closed Mondays, Thanksgiving Day, Christmas Day, and New Year's Day. The Morgan closes at 4 p.m. on Christmas Eve and New Year's Eve.????

Admission??$15 for adults; $10 for students, seniors (65 and over), and children (under 16); free to Members and children 12 and under accompanied by an adult. Admission is free on Fridays from 7 to 9 p.m. Admission is not required to visit the Morgan Shop.

??

Now, for the first time, the central role that drawing played in Flavin’s art will be explored in a major exhibition at The Morgan Library & Museum, opening on February 17, 2012. The show includes more than one hundred drawings by the artist—from early abstract expressionist watercolors of the 1950s and portraits and landscape sketches, to studies for his seminal light installations and late pastels of sailboats. In addition, the exhibition will feature nearly fifty works from Flavin’s personal collection of drawings, including nineteenth-century American landscapes by Hudson River School artists, Japanese drawings, and twentieth-century works by artists such as Piet Mondrian, Donald Judd, and Sol LeWitt. The exhibition will be on view through July 1, 2012.????

"The world knows Dan Flavin through the iconic fluorescent light installations on which his reputation rests," said William M. Griswold, director of The Morgan Library & Museum. "But few people are aware that these magnificent pieces often began as sketches, schematic drawings, and diagrams on graph paper. Throughout his career, Flavin turned to drawing to explore new ideas and new themes, and collected drawings by old and modern masters to serve as sources of inspiration. The Morgan is delighted to present this first-ever retrospective look at the key role that drawing played in the creative process of one of the twentieth-century’s most innovative artists."????

Early works

Dan Flavin: Drawing begins with the artist’s early drawings and watercolors. Landscapes are often the subjects of these works, and they reveal his interest in atmospheric and meteorological conditions, stemming from his training as a meteorological technician while in the Air Force. His admiration for Abstract Expressionists such as Willem de Kooning and Franz Kline led him to adopt a broad, gestural style. Particularly important among his works of the late 1950s is a group of watercolors with handwritten texts copied from the Bible, as well as from Irish and Chinese poetry and from James Joyce—a figure with whom the young Flavin identified, owing partly to their shared Irish heritage. ????

Early on Flavin began the practice, which he would continue throughout his career, of dedicating his works not only to friends and relatives, but also to historical figures and people whom he admired, such as Picasso and Cézanne. Some of these lengthy dedications express Flavin’s political and social engagement, as in the 1961 watercolor to those who suffer in the Congo, a reference to the crisis that ensued after the Congo achieved independence in 1960.????

Drawings for icons and related constructions??

Flavin’s first sustained series of constructions with light are the icons, created between 1961 and 1963. Each consists of a painted wooden square to which one or more lamps have been attached. Although only eight were fabricated, drawings document ideas for many more. Their collective title was inspired by the artist’s interest in Russian art of the early twentieth century, notably that of Kasimir Malevich, who referred to his abstract art as "the icon of my time." Likewise, Flavin compared his use of electric light to a modern type of icon. With characteristic irony, however, he noted that his icons "differ from a Byzantine Christ held in majesty; they are dumb—anonymous and inglorious . . . They are constructed concentrations celebrating barren rooms. They bring a limited light."??

The drawings for Flavin’s icons range from small sketches on 3 x 5 inch notebook pages—a favorite support for his working drawings—to large, finished studies in colored pencil or pastel. icon V (Coran Broadway Flesh) is the subject of several detailed drawings, probably because, with the number of lamps it includes, it is one of the most complex in the series, but also no doubt because Flavin considered it to be his best work at the time. It is "a perfectly resolved piece—symmetrical square of one color which is totally lighted," he wrote in his journal. Obsessed with keeping records of his work, Flavin drew several "inventories" of his icons, taking stock of those already made and planning future ones. Many drawings document various possible arrangements of several icons together, attesting that, although they were eventually sold individually, these works were first conceived as a group. ????

Drawings for fluorescent light installations

??From 1963 until the end of his life, the fluorescent light installations for which he is celebrated constituted Flavin’s main artistic production. These were first worked out in rapid sketches on the pages of the 3 x 5 inch notebooks he carried with him at all times. Using a fine ballpoint pen, Flavin combined visual and verbal notations, including such inscriptions as the color and dimensions of the lamps. Sometimes writing and drawing became one as Flavin literally "drew" the fluorescent tubes with the words designating their color. Some studies were on larger sheets, usually of 8 1/2 x 11 inch typing paper, a support that, like the notebook pages, demonstrated a preference for nonartistic paper. Indeed, Flavin did not treat his working sketches as master drawings. "For me, drawing and diagramming are mainly what little it takes to keep a record of thought...," he wrote. But his drawings were essential to his working process, and he carefully kept them. All were precisely dated and sometimes numbered to record the sequence in which they were made. ????

In the 1960s, Flavin also created finished drawings in preparation for his installations, using colored pencil and sometimes colored paper to suggest the interaction of the lights in the space. A few of these exist for the Green Gallery installation of 1964, Flavin’s first exhibition of fluorescent lights. As he became more familiar with the effects of lights, he no longer felt the need for such drawings. The later ones were made primarily for the market.

??

Beginning in 1971, Flavin kept visual records of his installations through what he called "final finished diagrams," carefully drawn in colored pencil on graph paper. These were not drawn by him but by others following his instructions—first his wife Sonja, and later his son, Stephen, and other assistants. The draftsperson’s initials appear on the sheet, next to Flavin’s signature. Delegating the actual making of a work is unusual with drawings, which are traditionally associated with the artist’s hand. But Flavin’s approach was in keeping with developments in Minimal and Conceptual art of the 1960s and 70s, which stressed the role of the artist as the person who conceives the work, though he may not be the one who actually executes it. This was notably the case with Flavin’s light installations. He planned them and closely supervised their placement, but the pieces, commercially available, were installed by electricians. ????

Landscapes, sails, and portrait drawings

??Perhaps the most unexpected aspect of Flavin’s drawing production is the numerous landscape sketches he made outdoors from observation. Particularly drawn to riverbanks and ocean shores, he often sketched views of the Hudson River and Long Island beaches. In these quick drawings, he would capture the mood of a scene in a few strokes. Working in series, he made many sketches from the same point of view in rapid succession. Unlike his studies for light installations, these drawings were made in traditional artists’ sketchbooks and in graphite pencil. Exercising the same care he took with his working studies, Flavin dutifully recorded the date, subject, and location of each sketch, sometimes even the weather conditions of the day on which it was made. For the purpose of exhibitions, he would frame many of them together, in sequences reflecting the order in which they were created.

??

During the 1980s, Flavin focused on the subject of sails in charcoal and pastel drawings whose spare composition and calligraphic qualities reflected his interest in Asian art. First drawn from observation, these were eventually made from imagination, allowing Flavin to draw them in any season. In addition to the landscapes, Flavin frequently drew portraits of his friends or of people he encountered by chance, for instance at restaurants or cafes. Often in ballpoint pen, these drawings can be found interspersed with sketches for light installations in Flavin’s notebooks. Rendered with quick, short marks, these likenesses often border on caricatures as the artist sought to catch his subjects’ salient features. ????

Flavin’s collection??

Highlights from Flavin’s collection include sheets by early-twentieth-century abstract painters such as Arp and Mondrian, both of whom he mentioned several times in his journal during the 1960s. Rather than finished drawings, Flavin sought sketches and studies, in which he found the most direct expression of the artist’s thoughts. Because of his own habit of working out his installations from quick notations on small pieces of paper, he felt a connection with artists like Mondrian, who could plan a painting by jotting down a few lines on the wrapper of a pack of cigarettes. Drawings by Hans Richter and George Grosz from the late 1910s and early 1920s are evidence of Flavin’s interest in the constructivist phase of Dada. ????

Flavin’s collection also includes many drawings—probably acquired through exchange—by his friends and contemporaries. A large sheet by the Chinese-American artist Wallace Ting is a reminder that it was he who introduced Flavin to sumi ink—a medium the latter used extensively in the late 1950s. Drawings by Donald Judd, Robert Morris, and Sol LeWitt evoke Flavin’s friendship with other artists associated with the Minimalist movement. He was particularly close to LeWitt, who has acknowledged the influence of Flavin’s concept of series on his own development, and to Judd. Earning his living as an art critic in the early sixties, Judd wrote several pieces on Flavin, praising "the power and complexity" of his work. Judd’s drawings in Flavin’s collection are related to his early Minimalist sculpture. Two elegant designs in gouache and pastel show that the two men shared the same interest in the use of color to create objects that combined aspects of sculpture and painting while being neither. ????

Flavin developed an interest in nineteenth-century American landscape drawings during the 1960s, especially after he moved to Cold Spring, in the Hudson River Valley, in 1965. His most intense period of acquisition of works by Hudson River School artists was 1979-81, when he bought a large number of them on behalf of Dia Art Foundation for the purpose of displaying them at a planned Dan Flavin Art Institute in Garrison, New York, a project that was never completed.

??

Flavin had a lifelong interest in Asian art as well, the influence of which is visible in his work from his early ink and charcoal drawings to his late pastels of sails. In the mid-1980s Flavin purchased over thirty Japanese drawings from Galerie Janette Ostier in Paris. Most of them date to the first half of the nineteenth century and are by artists associated with ukiyo-e (pictures of the floating world), such as Hiroshige, Hokusai, and Kuniyoshi. Japanese drawing epitomizes the combination of expressivity and economy that Flavin aimed to achieve in his own art.

??

Light installations at the Morgan??

Two major fluorescent light installations by Flavin will also be on view. At the entrance of the exhibition, visitors will encounter Flavin's untitled (to the real Dan Hill) 1a, 1978, a work composed of pink, yellow, green and blue light cast in two directions: out towards the viewer and back into the corner of the gallery. A spectacular corner installation, untitled (in honor of Harold Joachim) 3, 1977, an eight foot square grid, will suffuse the Clare Eddy Thaw Gallery on the ground floor with pink, yellow, green and blue light. Several studies related to this work are on view in the exhibition. ??????

Public Programs

??Family Program

??Glow Play: Sculpting with Light??

Saturday, February 25, 2-4 p.m.??

Artist and educator Nicole Haroutunian will invite children and their families to discover the drawings of Minimalist artist Dan Flavin. After visiting the exhibition and experiencing two of the artist's light installations first hand, they will then create color sketches inspired by Flavin's works on paper and shape glowing sculptures of their own.??

Adults: $6; Members: $4; Children: $2????

Gallery Talk ??

Dan Flavin: Drawing ??Friday, March 2, 7 p.m.??

With Isabelle Dervaux, Acquavella Curator, Modern and Contemporary Drawings??

Free????

Symposium ??Minimalist Drawing: The 1960s and 1970s??

Friday, April 27, 10:30 am-5 p.m.??

This symposium will explore the changing form, function, and status of drawing in the era of Minimalism and Conceptual art. Speakers to be announced. ??$15; $10 for Members; free to students with valid ID.????

Additional programs to be announced

????Organization and Sponsorship

This exhibition is supported in part by the Dedalus Foundation, Inc. and Nancy Schwartz, with additional assistance from The Aaron I. Fleischman Foundation. ??

Major funding for the catalogue is provided by Lannan Foundation. ????Dan Flavin: Drawing is organized by Isabelle Dervaux, Acquavella Curator of Modern and Contemporary Drawings at The Morgan Library & Museum.??

The Morgan exhibition program is supported, in part, by public funds from the New York State Council on the Arts and the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs.

The Morgan Library & Museum??

The Morgan Library & Museum began as the private library of financier Pierpont Morgan, one of the preeminent collectors and cultural benefactors in the United States. Today, more than a century after its founding in 1906, the Morgan serves as a museum, independent research library, musical venue, architectural landmark, and historic site. In October 2010, the Morgan completed the first-ever restoration of its original McKim building, Pierpont Morgan’s private library, and the core of the institution. In tandem with the 2006 expansion project by architect Renzo Piano, the Morgan now provides visitors unprecedented access to its world-renowned collections of drawings, literary and historical manuscripts, musical scores, medieval and Renaissance manuscripts, printed books, and ancient Near Eastern seals and tablets.????

General Information??

The Morgan Library & Museum??

225 Madison Avenue, at 36th Street, New York, NY 10016-3405

??212.685.0008??

www.themorgan.org????

Hours??

Tuesday-Thursday, 10:30 a.m. to 5 p.m.; extended Friday hours, 10:30 a.m. to 9 p.m.; Saturday, 10 a.m. to 6 p.m.; Sunday, 11 a.m. to 6 p.m.; closed Mondays, Thanksgiving Day, Christmas Day, and New Year's Day. The Morgan closes at 4 p.m. on Christmas Eve and New Year's Eve.????

Admission??$15 for adults; $10 for students, seniors (65 and over), and children (under 16); free to Members and children 12 and under accompanied by an adult. Admission is free on Fridays from 7 to 9 p.m. Admission is not required to visit the Morgan Shop.