December 5, 2012

Collecting and Transforming Medieval Manuscripts at The Getty

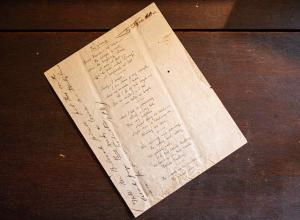

LOS ANGELES—For hundreds of years, medieval manuscripts have been bought and sold, gifted and stolen, preserved and rearranged, loved and forgotten, hidden and displayed, cut into pieces, hung on walls, and glued into albums. They have survived wars, fires, floods, religious conflict, political tumult, the invention of printing, and changes in taste. They have at times been valued for their beauty, for their spiritual significance, or simply for the strength of their parchment pages. Featuring works from the Getty Museum’s permanent collection, the Getty Research Institute, Hearst Castle, and other outside loans, Untold Stories: Collecting and Transforming Medieval Manuscripts, on view February 26-May 12, 2013 at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Getty Center includes medieval books, leaves, and cuttings with a variety of rich stories to be told.

The exhibition is the product of a collaboration between outside scholar and former Getty graduate intern Abby Kornfeld; the Getty Museum’s Kristen Collins, associate curator of manuscripts; and Nancy Turner, manuscripts conservator. The show offers a fascinating historical overview alongside a display of some of the Getty’s most treasured manuscripts. Each piece in the exhibition has its own ‘life story,’ whether it journeyed through the mountains of Peru or graced the courts of kings. Some manuscripts escaped unscathed, while others were damaged and painstakingly conserved.

The exhibition is the product of a collaboration between outside scholar and former Getty graduate intern Abby Kornfeld; the Getty Museum’s Kristen Collins, associate curator of manuscripts; and Nancy Turner, manuscripts conservator. The show offers a fascinating historical overview alongside a display of some of the Getty’s most treasured manuscripts. Each piece in the exhibition has its own ‘life story,’ whether it journeyed through the mountains of Peru or graced the courts of kings. Some manuscripts escaped unscathed, while others were damaged and painstakingly conserved.

“J. Paul Getty once referred to the ‘eventful lives’ led by art objects before they entered a museum’s collection. This exhibition explores the centuries of use and ownership of a number of manuscripts and is an excellent showcase for the research and conservation measures that take place before works are shown to the public,” explains Timothy Potts, Director of the J. Paul Getty Museum. “It also demonstrates the significance and value these precious objects held for their previous owners though the centuries.”

Eventful Lives

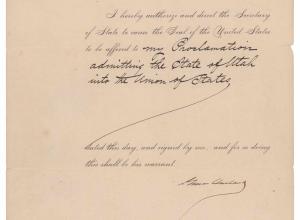

The provenance, or ownership history, of an object provides a record of the individual for whom the artwork was originally made as well as subsequent owners, when known. Evidence of ownership in manuscripts, including book plates, inscriptions, coats of arms, collectors’ marks, or notes tucked between the pages enable a reconstruction of the many hands through which these books passed. Catastrophic world events or even a simple change of ownership can obscure the origin of manuscripts, but diligent research can sometimes bring these tumultuous stories into view.

As was often the case throughout history, wars were a catalyst for the re-appropriation of manuscripts. This is demonstrated by the epic journey of the Getty’s famed Murúa manuscript, an illustrated history of the eminent line of Inca kings and their customs. The Spanish friar Murúa carried the manuscript throughout Peru before returning to Spain, where it became part of the royal collection, was seized as loot by Joseph Bonaparte and then finally surrendered to the Duke of Wellington, who brought the manuscript to England during the Napoleonic wars.

Additionally, pride of ownership often made new owners of manuscripts employ novel approaches to erasing the evidence of the previous owner, which makes the job of the researcher more difficult. For example, the Flemish manuscript leaf “Vasco de Lucena Giving his Work to Charles the Bold,” once featured the heraldic arms of the owner proudly painted on the lower margin. However, a later owner of the manuscript effaced the original patron’s coat of arms, painting over them with a decorative border, thus erasing his identity.

The Gothic Revival

The nineteenth century ushered in a widespread fascination with the Middle Ages. As a response to the cultural and social instability of the late 1700s and early 1800s, this bygone era came to be idealized for its perceived unity, piety, romance, and chivalry. The inspired and intricate craftsmanship of the medieval artist was celebrated as more authentic than the mass production of the modern age. This interest in the Middle Ages, sometimes called the Gothic Revival, led to the appreciation of medieval and Renaissance manuscripts as well as the creation of new ones—whether honest reproductions or forgeries that masqueraded as older works.

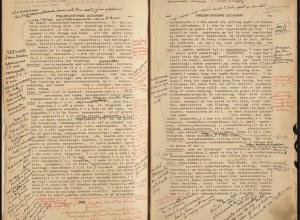

“The demand for illuminated manuscripts during the Gothic Revival led to a number of skilled and not-so-skilled forgeries,” notes Nancy Turner. “An example is an elaborately adorned manuscript leaf depicting the Roman emperor Augustus, which has been loaned to us by a generous collector. The forgery was accomplished by scraping the page clean of its decoration, then using original manuscripts as inspiration to repaint it. While the forger was an adept artist, he appears to have gotten the most basic technique wrong by applying gold leaf last, not first as medieval painters did.”

A particularly destructive practice took place in the 1800s alongside the renewed interest in medieval manuscripts, when illuminations were cut away from text in order to mount the cuttings into albums or in frames for a better viewing experience. These cuttings appeared in public museums and private homes and, while celebrating the art of illumination, further damaged or destroyed original pieces.

One of the more recent and startling manuscript transformations is a lampshade on loan from Hearst Castle in San Simeon, California. A medieval choir book, probably Spanish in origin, supplied the raw materials for the lampshade. Media mogul and art collector William Randolph Hearst commissioned architect Julia Morgan to create it, and was closely involved in its design. This provides a dramatic example of how manuscripts came to be valued as aesthetic rather than historical artifacts.

Repurposing Manuscripts

As their utility and efficacy changed, medieval manuscripts were sometimes refashioned to serve a different purpose. For books whose liturgical or devotional use might have become outmoded, picture cycles were presented in a new format to fulfill a more current function. With the invention of printing, centuries-old manuscripts were replaced by mechanically produced books. Since the earlier volumes were no longer needed, they came to be valued not for their text or images but for the strength of their parchment pages.

In 1540, one English commentator complained that cuttings from manuscripts were being used as rags to clean shoes and candlesticks, as grease-proof wallpaper, as jam jar covers, as gun wadding, and for sale to grocers, soap sellers, and book binders. An example of this kind of repurposing is a Bible that was written and illuminated in the abbey of Saint Martin at Tours in the 800s. Once valued for its beauty and didactic qualities, the book was dismantled in the fifteenth century and used to reinforce the bindings of early printed books. Pages were cut into thin strips that served as sewing guards, preventing widening of the sewing holes in the soft, handmade paper.

“One of the reasons manuscripts have survived over the centuries is their portability—they’ve been rescued from burning buildings and carried off by monks who were evicted from their monasteries,” says Collins. “Having entered the possession of the museum, the manuscripts will lead slightly less eventful lives, as they are exhibited for the public, studied by scholars, and kept safe for years to come.”

Untold Stories: Collecting and Transforming Medieval Manuscripts will be on view February 26-May 12, 2013 at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Getty Center. The exhibition is curated by outside scholar and former Getty graduate intern Abby Kornfeld; Kristen Collins, associate curator of manuscripts at the J. Paul Getty Museum; and Nancy Turner, manuscripts conservator at the J. Paul Getty Museum.

# # #

The J. Paul Getty Trust is an international cultural and philanthropic institution devoted to the visual arts that includes the J. Paul Getty Museum, the Getty Research Institute, the Getty Conservation Institute, and the Getty Foundation. The J. Paul Getty Trust and Getty programs serve a varied audience from two locations: the Getty Center in Los Angeles and the Getty Villa in Malibu.

The J. Paul Getty Museum collects in seven distinct areas, including Greek and Roman antiquities, European paintings, drawings, manuscripts, sculpture and decorative arts, and photographs gathered internationally. The Museum's mission is to make the collection meaningful and attractive to a broad audience by presenting and interpreting the works of art through educational programs, special exhibitions, publications, conservation, and research.

Visiting the Getty Center

The Getty Center is open Tuesday through Friday and Sunday from 10 a.m. to 5:30 p.m., and Saturday from 10 a.m. to 9 p.m. It is closed Monday and major holidays. Admission to the Getty Center is always free. Parking is $15 per car, but reduced to $10 after 5 p.m. on Saturdays and for evening events throughout the week. No reservation is required for parking or general admission. Reservations are required for event seating and groups of 15 or more. Please call (310) 440-7300 (English or Spanish) for reservations and information. The TTY line for callers who are deaf or hearing impaired is (310) 440-7305. The Getty Center is at 1200 Getty Center Drive, Los Angeles, California.

Additional information is available at www.getty.edu.

Eventful Lives

The provenance, or ownership history, of an object provides a record of the individual for whom the artwork was originally made as well as subsequent owners, when known. Evidence of ownership in manuscripts, including book plates, inscriptions, coats of arms, collectors’ marks, or notes tucked between the pages enable a reconstruction of the many hands through which these books passed. Catastrophic world events or even a simple change of ownership can obscure the origin of manuscripts, but diligent research can sometimes bring these tumultuous stories into view.

As was often the case throughout history, wars were a catalyst for the re-appropriation of manuscripts. This is demonstrated by the epic journey of the Getty’s famed Murúa manuscript, an illustrated history of the eminent line of Inca kings and their customs. The Spanish friar Murúa carried the manuscript throughout Peru before returning to Spain, where it became part of the royal collection, was seized as loot by Joseph Bonaparte and then finally surrendered to the Duke of Wellington, who brought the manuscript to England during the Napoleonic wars.

Additionally, pride of ownership often made new owners of manuscripts employ novel approaches to erasing the evidence of the previous owner, which makes the job of the researcher more difficult. For example, the Flemish manuscript leaf “Vasco de Lucena Giving his Work to Charles the Bold,” once featured the heraldic arms of the owner proudly painted on the lower margin. However, a later owner of the manuscript effaced the original patron’s coat of arms, painting over them with a decorative border, thus erasing his identity.

The Gothic Revival

The nineteenth century ushered in a widespread fascination with the Middle Ages. As a response to the cultural and social instability of the late 1700s and early 1800s, this bygone era came to be idealized for its perceived unity, piety, romance, and chivalry. The inspired and intricate craftsmanship of the medieval artist was celebrated as more authentic than the mass production of the modern age. This interest in the Middle Ages, sometimes called the Gothic Revival, led to the appreciation of medieval and Renaissance manuscripts as well as the creation of new ones—whether honest reproductions or forgeries that masqueraded as older works.

“The demand for illuminated manuscripts during the Gothic Revival led to a number of skilled and not-so-skilled forgeries,” notes Nancy Turner. “An example is an elaborately adorned manuscript leaf depicting the Roman emperor Augustus, which has been loaned to us by a generous collector. The forgery was accomplished by scraping the page clean of its decoration, then using original manuscripts as inspiration to repaint it. While the forger was an adept artist, he appears to have gotten the most basic technique wrong by applying gold leaf last, not first as medieval painters did.”

A particularly destructive practice took place in the 1800s alongside the renewed interest in medieval manuscripts, when illuminations were cut away from text in order to mount the cuttings into albums or in frames for a better viewing experience. These cuttings appeared in public museums and private homes and, while celebrating the art of illumination, further damaged or destroyed original pieces.

One of the more recent and startling manuscript transformations is a lampshade on loan from Hearst Castle in San Simeon, California. A medieval choir book, probably Spanish in origin, supplied the raw materials for the lampshade. Media mogul and art collector William Randolph Hearst commissioned architect Julia Morgan to create it, and was closely involved in its design. This provides a dramatic example of how manuscripts came to be valued as aesthetic rather than historical artifacts.

Repurposing Manuscripts

As their utility and efficacy changed, medieval manuscripts were sometimes refashioned to serve a different purpose. For books whose liturgical or devotional use might have become outmoded, picture cycles were presented in a new format to fulfill a more current function. With the invention of printing, centuries-old manuscripts were replaced by mechanically produced books. Since the earlier volumes were no longer needed, they came to be valued not for their text or images but for the strength of their parchment pages.

In 1540, one English commentator complained that cuttings from manuscripts were being used as rags to clean shoes and candlesticks, as grease-proof wallpaper, as jam jar covers, as gun wadding, and for sale to grocers, soap sellers, and book binders. An example of this kind of repurposing is a Bible that was written and illuminated in the abbey of Saint Martin at Tours in the 800s. Once valued for its beauty and didactic qualities, the book was dismantled in the fifteenth century and used to reinforce the bindings of early printed books. Pages were cut into thin strips that served as sewing guards, preventing widening of the sewing holes in the soft, handmade paper.

“One of the reasons manuscripts have survived over the centuries is their portability—they’ve been rescued from burning buildings and carried off by monks who were evicted from their monasteries,” says Collins. “Having entered the possession of the museum, the manuscripts will lead slightly less eventful lives, as they are exhibited for the public, studied by scholars, and kept safe for years to come.”

Untold Stories: Collecting and Transforming Medieval Manuscripts will be on view February 26-May 12, 2013 at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Getty Center. The exhibition is curated by outside scholar and former Getty graduate intern Abby Kornfeld; Kristen Collins, associate curator of manuscripts at the J. Paul Getty Museum; and Nancy Turner, manuscripts conservator at the J. Paul Getty Museum.

# # #

The J. Paul Getty Trust is an international cultural and philanthropic institution devoted to the visual arts that includes the J. Paul Getty Museum, the Getty Research Institute, the Getty Conservation Institute, and the Getty Foundation. The J. Paul Getty Trust and Getty programs serve a varied audience from two locations: the Getty Center in Los Angeles and the Getty Villa in Malibu.

The J. Paul Getty Museum collects in seven distinct areas, including Greek and Roman antiquities, European paintings, drawings, manuscripts, sculpture and decorative arts, and photographs gathered internationally. The Museum's mission is to make the collection meaningful and attractive to a broad audience by presenting and interpreting the works of art through educational programs, special exhibitions, publications, conservation, and research.

Visiting the Getty Center

The Getty Center is open Tuesday through Friday and Sunday from 10 a.m. to 5:30 p.m., and Saturday from 10 a.m. to 9 p.m. It is closed Monday and major holidays. Admission to the Getty Center is always free. Parking is $15 per car, but reduced to $10 after 5 p.m. on Saturdays and for evening events throughout the week. No reservation is required for parking or general admission. Reservations are required for event seating and groups of 15 or more. Please call (310) 440-7300 (English or Spanish) for reservations and information. The TTY line for callers who are deaf or hearing impaired is (310) 440-7305. The Getty Center is at 1200 Getty Center Drive, Los Angeles, California.

Additional information is available at www.getty.edu.