Reynolds Price, Author, “Fellow Bibliomaniac”

Reynolds Price, a true southern gentleman and one of the outstanding American writers of his generation, died yesterday at 77, in Durham, North Carolina, of heart failure. While known best for his thirteen novels, Price was a magnificent stylist adept in many genres, with volumes of poetry, essays, plays, short stories, memoirs, and translations from the Bible among his other credits. His first book, A Long and Happy Life, was greeted on its release in 1962 with immediate acclaim and honors, including a coveted William Faulkner Award that set the stage for the many literary triumphs that followed, A Generous Man (1966), Kate Vaiden (1986) and The Three Gospels (1996) notable among them. His third memoir, An American Writer, Coming of Age in Oxford (2009), recalled the three years he spent as a Rhodes Scholar in the late 1950s; upon his return to the United States, he taught at Duke University, his alma mater, for more than fifty years, a favorite course among students the one on his lifelong hero, John Milton. A splendid obituary of Price's life--with some lovely comments from such admirers as Allan Gurganus and Ann Tyler--appears in today's New York Times.

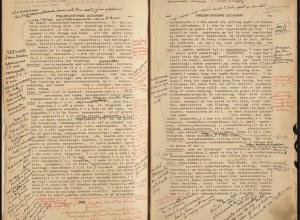

Let it also be said that in addition to his remarkable body of work—thirty-eight published books, by my count—Reynolds Price was a dedicated bibliophile who had a genuine appreciation for books as artifacts. I spoke with him several times back in the 1990s for my newspaper columns, the most memorable get-together coming on May 15, 1992, when we met for lunch at a small cafe just off Harvard Square to talk about his novel Blue Calhoun, which had just been released. As much as I treasure the inscription he wrote in my copy of the book, pictured here—how could I not love being referred to by Reynolds Price as a "fellow bibliomaniac?"—the unqualified highlight of the interview came when we were discussing his courageous battle with spinal cancer, and his will to continue writing despite being confined to a wheelchair as a paraplegic. It was during this exchange that Price told me about a special book he owned, and why it meant so much to him. A phrase he used—"touching the hand"—inspired me sufficiently to use it three years later as the title for the opening chapter in A Gentle Madness. "Milton wrote his best books after he lost his sight," he had told me back then. "I have written eleven books since I had cancer, and it represents some of the very best work I have ever done. My copy of Paradise Lost once belonged to Deborah Milton Clarke, the daughter who took Milton's dictation after he went blind. For me, it was like the apostolic succession. I was touching the hand that touched the hand that touched the Hand." When I contacted Price two years later to go over the quote once again—he was delighted to learn that I was going to use it in my book—he reminded me to make sure that the 'h' in the final usage of the word 'hand' be capitalized. "This is the Hand of God we are talking about here, Nicholas," he said in his wonderful drawl. I get chills to this day thinking about it.